Patients come to us for medical assistance, but sometimes end up helping us instead

On a slightly weary Thursday evening, just as I was about to go into surgery at 6 PM, I got a frantic phone call from a son about his 75-year-old father. “For the past few days, my father’s balance has been off. But since this morning, his speech has been slurring, and he’s becoming incoherent and confused. It almost seems like he’s slipping in and out of consciousness,” the son went on, slightly frenzied.

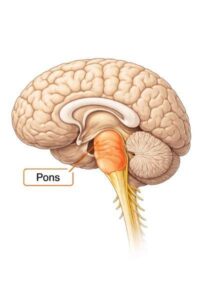

“We took the advice of our family physician and got a CT scan of the brain. We’ve been told he’s slowly bleeding into the brain and needs an emergency operation,” came the vague description from the other end.

“Why don’t you take him to the hospital closest to you,” I suggested, channelling my inner GPS. “Doctor, we live in Juhu. Do you come this side of town?” I politely declined. “Even in his completely incoherent state, the only thing my dad keeps saying is, ‘Take me to Mazda. I’ve read every single column of his in the paper and I know he’ll be able to fix me!’” the son pressed on, almost panting on the other end. “He’s a big fan and a very stubborn one. Please do something,” he urged. “He keeps chanting ‘Mazda, Mazda’, as if it’s a medical mantra.”

To be honest, I had a huge smile on my face, almost blushing a little. Until now, I thought my fan base consisted primarily of 70-year-old women, and it was good to have some male cheer – a dopamine boost mixed with some testosterone. It took away the tiredness of a long Thursday, after having done a 6-hour brain tumour surgery followed by a 3-hour spine operation. “Bring him to my hospital and we’ll see what we can do. I’m just going into surgery, but the team in the ER will evaluate you and then call me. I’ll come and see him,” I said, hoping it would be a quick fix and not a full-blown renovation. “Thank you, doctor, we’ll be there in an hour,” he sounded relieved.

As we were operating on our third case of the day, I told my colleague that I had started writing a few years ago to help people understand brain and spine problems so that they could make informed decisions about their health and become aware of what conditions to promptly treat and what could be ignored. “Today, I feel we succeeded!” I told him, as we put a tube into the brain of a young girl that had an excess accumulation of fluid.

Two hours later, Aspi was in the ER with his two children who looked exactly like him. His wife was also present, a shawl wrapped around her neck. When I went to see him, he looked like he’d wrestled a bear and lost, a classic emergency room look: his hair was dishevelled and shirt incorrectly buttoned. Nonetheless, he recognized me despite his deeply confused state. Score one for the ego! I quickly examined him to make sure he was moving his hands and legs. “But he can’t walk,” the son interjected. The CT scan had showed a collection of blood on both sides of his brain that was building up after a fall he had had a few weeks ago that had now reached tipping point.

“He’ll need an operation to drain the blood,” I said. “When, doctor?” they asked. “Now-ish!” was my response. “We’ll do whatever you say,” they agreed, after I gave them a detailed explanation of the procedure and possible outcomes. “He’ll be home in 3 days,” I assured them. They looked relieved. “Achha, doctor, we forgot to mention that he had epilepsy for many years but has stopped his meds since over a decade, as he’s been seizure free,” they added. “Not to worry,” I said after enquiring about it in detail.

Within hours, the whir of the drill echoed in the sterile theatre as we punched two coin-sized holes through Aspi uncle’s skull, cut the dura, and let out a pool of blood that had collected below it. It was like an overflowing river whose flood gates had just been opened. We wheeled him out at midnight, his eyes glowing at the surprise of finding himself alive. “We’ve kept a tiny tube inserted to drain the blood over the next few days, and once that stops, we’ll send him home.” They were thrilled and thanked me for being so prompt, enamoured by how the whole thing had gone off without a glitch. Their gratitude was a tangible thing, a warmth that filled the room, a stark contrast to the cold steel of the operating table.

The next morning, Aspi uncle had a seizure. His eyes rolled up, his mouth started frothing, and his hands and legs jerked uncontrollably against the crisp white sheets of his bed. We controlled it with medication, but he was knocked out and not waking up. The CT scan looked clean. The family was shaken, as was I. Had I taken the past history of his epilepsy lightly, I wondered. Should we have given him some prophylactic medicines?

‘Never meet your heroes. If you meet your heroes, you’re always going to be disappointed,’ the old adage echoed. They saw a saviour, a celestial figure, but I was a mere mortal. Thankfully, there was nothing to worry about, as Aspi uncle soon regained consciousness and was back to his normal self. He was discharged a few days later, walking in perfect balance, alert and coherent, able to recount several articles of mine he’d read.

When he returned two weeks later, he was beaming. “He’s been walking 7-8 km a day!” his son said. The scars of surgery had disappeared into oblivion, both literally and metaphorically.

“I want to show you something about the work we do with Tata Institute of Social Sciences,” he told me, pulling out two mirrors. One was perfect, the other shattered. “Look into the good mirror and tell me three positive attributes about yourself,” he suggested. I paused, shrugging my shoulders even though I wanted to say ‘competent’, ‘funny’, and ‘kind’. “Most people are unable to say anything good about themselves,” he told me. “Look into the cracked mirror and what do you see?” “The same person,” I told him, “But slightly fractured.” “It’s not you who’s fractured; it’s just the image of you that’s broken,” he clarified. “Most people are unable to identify the difference, and that’s why we conduct workshops with cancer patients at Tata Memorial Hospital and in schools and colleges to assist people with mental health issues to help them rebuild themselves.” “I’m going to keep these,” I told him. “We got them for you!” they thanked me profusely, as the wife gave me a hand-made painting and a whole lot of other paraphernalia.

Every time I feel like I’m not good enough, I look into the broken mirror and remind myself it’s just an image. Not the real thing. That I’m whole inside. That I’m more than enough.

There is something to learn from everyone. Thank you, Aspi uncle and family, for allowing us to treat you. It is I who is your fan.

20 thoughts on “The surgical fan”

I am a big fan. How you create main in our minds with your words!

Hope you know your true value now, even just going through all your episode on surgery gives mental and physical confidence In a person so next time don’t ever bother to look into THAT BROKEN MIRROR. Bless you and keep up your excellent work. AMIN.

Awwww Doc,

It’s your humbleness personified.

Dignity seems to be embedded in you.

Loved that Mazda

If you are running short of 70 year old male fans, I’m here doc. A permanent fan who you have given a new life. You’re a Miracle worker and will always be a benefit to mankind. Thanks doc and God bless. We, my wife Smia and me will always knock on your door when there’s trouble or not.

Wow. That was some serious story and a lesson to learn. Thanks for sharing. Very inspiring and informative. Best wishes always

Farida Mody.

Dear Mazda

A very good article as always! Faith heals. The patient’s faith in you had already healed him to a great extent.Such is the power of faith and healing, a mutual level of confidence and comfort between the patient and his doctor. And yes, there’s a lot to gain from the knowledge you open up for us with respect to your surgeries. You are a good doctor and a fine man

I hope I never have to go under the surgeon’s knife at least for neurological matters, but if I ever do, I hope the operating surgeon is Mazda Turel

Enjoyed reading yet another lovely article. You should publish a book of all your articles.

Doctor you are a very kind hearted person and gentle. You give courage and boost the patient and his relatives. God almighty bless you and give you strength and success in all your endeavours always.

Very kind hearted person and even though you had already performed two operations, you attended to the third gentleman.

God bless you and always be by your side and it is God almighty who is always there by your side in the operation theatre and it is HE who is performing the operation.

Dearest Dr Mazda sir …….

Thanks for lovely piece as usual again inside OT wrapped in with your MALE FAN 🌹

It’s matter of great pride for surgeon cum writer whose fan following are increasing leaps & bounds…..❤️

The ups & down post surgery is like Roller coaster ride for layman like us but you explain us as usual as if we are inside your ICU ❤️❤️

May Lord bless you to blush you more & more with many more Aspi uncles 😍

When patients start chanting your name like a medical mantra, you know you’ve truly arrived.

Mazda…Mazda…Mazda…the neurosurgeon with a fan following rivalling rockstars. Saving lives and winning hearts, one brain at a time

I am speechless Doc. GOD bless you 🙏🤗

God bless u for ur profound inbuilt humanity !

That’s great.

The most satisfying situation.

It takes a lot of patience and hard work to achieve it.

Best Wishes Dr Mazda 🌷

That’s great.

The most satisfying situation.

It takes a lot of patience and hard work to achieve it.

Best Wishes Dr Mazda 🌷

Whenever I read an article by Dr. Mazda it reminds me how miracles do occur and Life is Beautiful😇

Liked the two mirrors therapy 🙂

SAVIOUR YOU ARE… BEST LUCK

I’m still learning from you, but I’m making my way to the top as well. I absolutely love reading everything that is posted on your site.Keep the aarticles coming. I loved it!