A gentleman who proclaimed that he lived to eat shaved off 10 kg and a tumour.

Are we really what we eat?

“Good evening, doctor saab!” Jayesh bhai walked in with his wife to meet me. The couple were in their mid-fifties and seemed pretty jovial. He had a round face that sat atop an even rounder torso. The buttons of his bright yellow shirt were struggling to keep its two halves together. Through two of those buttons, his navel looked like his third eye, staring me in the face. Sensing my unwavering gaze from his centre of mystical enlightenment, his wife remarked, “He loves to eat,” which I acknowledged, because I do too. “And I love to cook for him,” she continued dotingly.

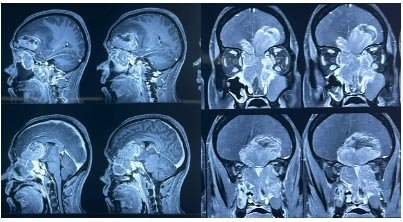

It was of little concern to them that Jayesh bhai had a brain tumour. “I was having headaches and my GP asked me to do an MRI. He said he had heard a lecture of yours where you mentioned that people with headaches should get an MRI,” he explained. I peered through the scan to note it was a craniopharyngioma – a benign tumour with a malignant pronunciation. It was arising from the pituitary stalk and pressing against his hypothalamus – the control centre for hunger and satiety besides a myriad of other functions such as regulating hormones, body temperature, heart rate, blood pressure, thirst, mood, sleep and sex drive. He had no issues with any of the other functions, he clarified, and his wife confirmed. The weight he was putting on had simply been attributed to his love for food. I explained to them that not everyone who lives to eat has a brain tumour, but subtle shifts of patterns should not be neglected. He had put on over 20 kg in the past 6 months.

“Can I continue to eat dhokla, khandvi, and undhiyu before surgery?” he questioned, listing out his favourite food items. “Of course,” I said without hesitation, “but we will need to check your hormone and sugar levels,” I cautioned. I detailed a battery of blood investigations and booked an appointment with our endocrinologist, who helped manage such patients perioperatively. Before leaving, he asked, “Is it true that you become hot tempered if you consume too much spicy food?” He smiled at his wife, who shook her head, denying the allegation. “It’s possible,” I said, having read this in a publication. “I’m telling her to eat more sweets but she’s just not listening,” he said, as both of them left the room laughing.

He came back really upset a few days later. “The endo doctor you sent me to has stopped all my desserts! No chocolate, no cake, no jalebi, no gulaab jamun, not even aam ras! Season is about to be finished. What does one eat?” He questioned, disapproving of medical nutrition. “One day, science will show that sugar is really good for us and the whole medical community will have to eat its words,” he muttered, disgruntled. “As long as we are eating only words, we won’t put on any physical weight,” I punned, only later realizing that the emotional burden of eating one’s own words is even heavier. “Let us quickly get over with the surgery, so that I don’t have to deal with all these dietary restrictions,” he told me. I agreed, adding, “It’s also possible that you might not want to eat as much after surgery relieves the pressure on your hypothalamus,” and I watched his face shrink with dismay.

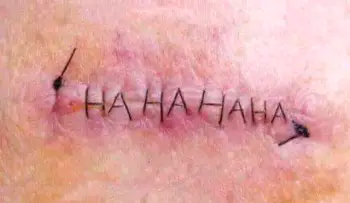

Patients often ask what foods to avoid after brain or spine surgery, and unless they have a specific medical condition, my answer is always peppered with the sagacity of ancient wisdom: Everything in moderation is okay. I advise them on eating fresh fruits and vegetables and to go easy on the carbs and avoid red meat. People wonder if certain foods will affect wound healing or cause a tumour to grow back. They wonder even more if eating too many pizzas, dosas, or spring rolls might have caused the tumour in the first place. I also often get asked what foods are good for the brain, and the answer is berries, nuts, green leafy vegetables, avocado, fish, and eggs. And, if you’re Parsi, eggs on top of eggs. The foods we eat should bring us both health and happiness.

We operated on Jayesh bhai a few days later. The tumour had a large cyst with golden fluid within it, resembling the crystalline oil his jalebis were fried in. We peeled it off the hypothalamus and the pituitary stalk in the hope of restoring his internal balance. “Your hospital food is very tasty,” he proclaimed, sipping on cream of tomato soup, but with his eyes fixated on the pudding next to it. “Can I eat pav bhaji at home?” he asked, before getting discharged. I nodded. “And a small drink once in a while is okay?” he winked. I granted permission with a big smile.

According to a lot of data, research, and science, we are what we eat. But we are also the five people we spend most of our time with. We are the culmination of the experiences of our several lifetimes. We are the ratio of the suffering we caused and the suffering we endured. We are the failures we were unable to fathom or the success we were able to surpass. We are the hopes we racked up and the sorrows we shared. We are the strings we pulled and the ropes we hung on to. We are how stoically we portray ourselves and also how vulnerable we might choose to be. We are the questions that quench and the answers that ask more questions. We are the ships we sailed in and we are also the ships we saluted from the shore. We are our insight and intuition. We are our hunger and our cravings, our weight gain and our weight loss. We are the stories we tell ourselves. We are all. We are one.

Jayesh bhai came back three months after surgery for a follow up. He had lost ten kilos. Now he was Jayesh bhai Jordar. His shirt fit well. The third eye had closed. “Doctor saab!” he greeted me in his trademark fashion handing me a box of chocolates. “Can I eat sweet and sour pickles that may sometimes be spicy also?” I don’t know if there was any item on the menu that he hadn’t cross-checked with me in our time together. “Besides human beings, you can eat whatever you want,” I professed with folded hands.