A tumour stuck to an ‘arrogant’ vein reminds this surgeon about the need to exercise discretion

A 28-year-old slammed his MRI films on my desk, profusely sobbing away without my having the slightest clue of what was going on. He was lean, well-built and wore track pants and a tight-fitting white shirt. I waited patiently till the wailing ebbed and made way for intermittent snivels, which he wiped away with the tissue I’d handed him. His wife sat next to him with her hand on his back, gently patting it until his face was dry, his eyes remaining swollen and bloodshot.

“I have a 6-cm malignant brain tumour,” he lamented, his first words to me as he tried to come to terms with how his life had changed with a single scan of the head. “What prompted your doctor to get a scan?” I enquired in my ‘I’ve got his under control’ voice, calmly guiding the conversation to become less dramatic. “I had headaches for a week, which weren’t getting any better, and then I started waking up with them,” he answered. “Any blurring of vision, nausea, vomiting, imbalance while walking?” I asked as a routine follow-up question, a yes to which might suggest raised intracranial pressure. “No!” he shook his head in disbelief, clearly thinking that at least a few of those symptoms should have been present if his headache was this serious.“They don’t have to be,” I replied, explaining, “Headaches don’t read text books. I’ve gone hoarse telling people that if a headache doesn’t settle down in a few weeks, it warrants a scan. Nine times out of ten it’ll be normal, but I can show you dozens of patients with brain tumours, and all they had was a dull aching headache!”

On examination, I found his neurological status to be intact. His eye movements were okay, the motor and sensory function in his limbs was fine, and he walked heel to toe without losing his balance. I plugged the MRI films into the viewing box and peered through it very intently. I went through the entire set of 8 films that showed the tumour in different dimensions. I scanned through the accompanying report once again. The couple waited with trepidation for my verdict.

“This is not malignant for sure,” I decreed. “But the report says it’s a medulloblastoma,” the man exclaimed, “and I’ve been reading about it online and it’s supposed to be a highly malignant tumour. I’ve been devastated all weekend knowing I have only a few years to live.” I reached over to reassure him. “This is a meningioma. It’s a benign tumour arising from the tentorium, the dural layers that separate the forebrain from the hindbrain. Because its grown so big, it’s compressing the 4th ventricle and the brain stem and pushing the cerebellum apart. The guys at the scan centre have mistakenly inferred this to be a malignant tumour because one is commonly seen in this location. Trust me, I know what I’m talking about,” I reiterated, carefully studying the frayed margins of the tumour on the scan and pointing it out to him.

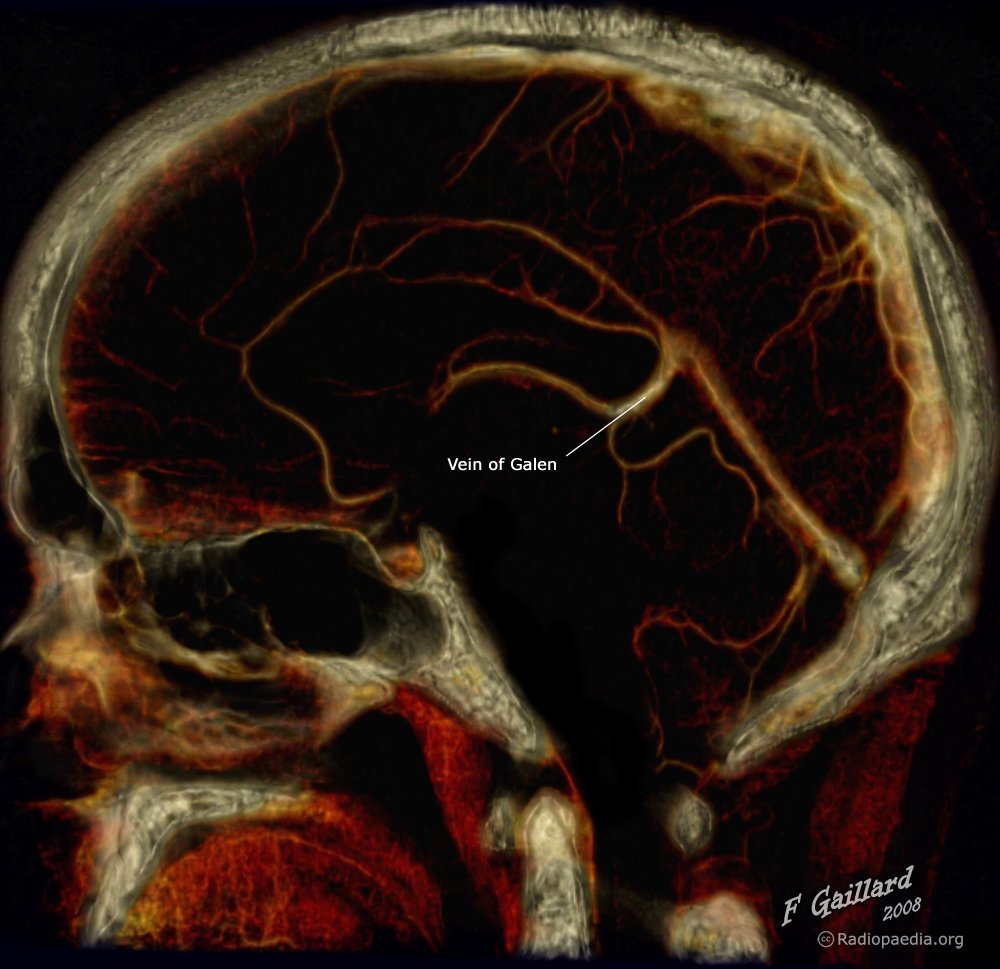

“This is a huge relief, that this is not malignant,” he said, still looking at me in disbelief. “But we still have to take care of your headache by removing this, and it’s a technically formidable operation,” I admitted. “It’s stuck to the vein of Galen, one of the main veins that drains the deep venous system. If that gets injured, you could be in a coma. Galen was the Greek physician to describe it,” I said, adding on some trivia to lighten the mood. I explained to him all the possible routes we could use to reach the meningioma given that it was smack in the centre of the brain. He was ready. I called up and booked the operation theatre for a 12-hour slot the following week.

A few days later we positioned him Concorde. It’s where the patient is turned prone and the head is raised above the level of the body and then flexed to resemble the design of the plane. This gives us a straight shot at the target. We made an incision down the back of his head up to where it met the neck, getting down to the bone, which we removed as a flap to put back later. The cerebellum was very tense. We drained some cerebrospinal fluid after opening the dura and appeased it. “Never retract a swollen brain,” I remembered the teachings of my mentor. We kept releasing the brain fluid until the cerebellum was almost sulking.

Choosing a narrow corridor below the tentorium and above the cerebellum, we encountered the tumour. As I had predicted, it was attached to the under-surface of the tentorium. I coagulated it with bipolar forceps, killing its blood supply and turning a fiery ball into its ashen counterpart. I used an ultrasonic aspirator and gobbled up the core, allowing the tumour to fall on itself, after which we daintily peeled it off the surrounding brain that it was pushing against.

The surgery carried on elegantly for several hours until we approached the very end, when my assistant cut into the last bit of tumour and it bled profusely. “Shit,” I swallowed a few expletives, “is that the vein of Galen?” My heartbeat was racing uncontrollably. We controlled the bleeding in a series of quick synchronized manoeuvres and concluded that it was a tumour vessel. The vein of Galen was just behind it, pulsating arrogantly, cautioning us to beware of it. Not wanting to tempt fate, we left a few millimetres of the tumour on the vein. “It’s benign,” I told my colleague, “Nothing’s going to happen.” Discretion is the better part of valour, we’ve learned in medicine.

Galen was the author of more than 500 papers, and gave his name to the great cerebral vein (of Galen) and also to the nerve of Galen, the communicating branch of the internal laryngeal nerve with the recurrent laryngeal nerve, all of this before he died in 200 AD. During his brilliant career, Galen compiled more than 300 books, of which around 120 are still available for our study. It is a small wonder, then, that this medical colossus reigned like a dictator over the world of medical science for almost 1,500 years.

Our patient woke up the next morning with his speech slightly slurred, his eyes bobbling a little and his balance all over the place. “All these are indications of where we’ve fiddled around, and it’ll settle down,” I reassured him, and he noticed the improvement himself over the course of a few days. By the time he was discharged, he wanted to ballroom dance with me. There, too, discretion was the better part of valour.