(Pushing) The surgical envelope

A man with a tumour and blurred vision insisted he wanted to see again because without sight, it’s no fun. Fair. Except, he was 96

Babulal was gradually losing his vision. Everything was a fuzzier version of what it used to be. The entire day appeared to him as if it were always late evening. An MRI of the brain showed a pear-shaped tumour arising from the pituitary gland and pressing against the optic nerves. The only option available to restore his sight was surgery. The only caveat was that he was 96 years old; 96 and a half, to be precise.

He sat in my office with his granddaughter who was an anaesthetist – thankfully, because she comprehensively understood the complications of ‘putting someone under’ at this age. His round head and pointed nose with cavernous nostrils were offset by a Dalai Lama type of smile, oblivious to the implications of life and death I was discussing with her. “The entire family has been dissuading him to have surgery at this age, and the two doctors we went to before coming to you bluntly refused to operate on him, but he is hell-bent on getting his vision back,” she told me, also informing me of the two stents in his heart. “But apart from that, he is quite fit, walks with a stick, and is mostly independent,” she added, pulling out the list of medications he was on. When I examined him, he could barely count fingers close to his face.

“Why do you want to have surgery? I asked Babulalji. He couldn’t hear very well until he adjusted his hearing aid, gesturing to me to repeat the question. “Why do you want to have surgery?” I bellowed. He paused for a brief moment and then answered in Gujarati, “Majha nathi aavati” (I’m not having fun). It was the most succinct explanation of how he wanted to live his life – choosing for himself, joy over everything else. He was the patriarch of a 65-member extended family, several of whom were doctors in India and the United States, all of them wary of his having surgery. “I have only one request,” he tightly grasped my forearm and pulled me closer. “Either you make me well or send me up, vachma na raktha (don’t keep me lingering in-between if something happens).” I thanked him for the added pressure as the family broke out into smiles.

While they were finalizing the logistics required for the family to arrive from abroad, I was contemplating whether it was the correct decision to offer surgery. “He can’t hear very well; what’s the problem if he can’t see?” someone reasoned. Friends who I spoke to about this suggested that “he might have chosen you to help him with his exit strategy,” which worried me even more. Senior colleagues made the point that “even if he dies from an anaesthetic complication, the buck will eventually stop with you.” All I was interested in was giving him back his vision, but I also understood that it came with a ginormous flipside.

A couple of weeks later, the entire family assembled for a final discussion. “He is our everything,” said his nephew, a doctor who had flown down from America with his wife. “But we also accept with folded hands any outcome that this decision bears.” It was an extremely gracious statement to make coming from someone who had practiced medicine in the United States for over 40 years, a country fraught with litigation. “I left India with 10 dollars in my pocket, and today, by the grace of God, our entire family is very comfortable,” he smiled, lovingly inviting me over to visit him soon.

It amazes me how every Gujarati who left for America in the 70s did so with exactly 10 dollars in their pocket. Every rags to riches story I’ve heard has this definite staple amount. Nothing more, nothing less. I’m sure there must have been at least a few who left with a couple of hundred bucks? If you did so and happen to read this, please give me a shout out. Isn’t 10 dollars too much of a gamble? Unless you were heading straight to Vegas.

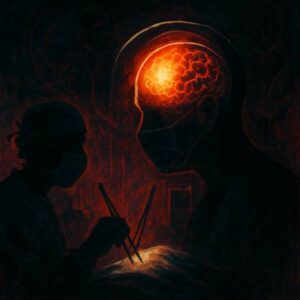

After meticulous planning with our anaesthesia and ICU teams, we took him into the operating theatre on a day when all the planets aligned. His nephew, who was an ER physician, requested to watch the surgery and I willingly obliged. With the help of my ENT colleague, we entered his gigantic nose, nibbling away at the bony ridges that resembled the mountains of Leh. The tumour had eroded the bony saucer-shaped floor on which the pituitary gland straddled itself. I made some room around to expose it adequately and cut into it, allowing for the cheesy-oozy tumour to emanate itself. We curetted the walls to ensure nothing was left behind and the optic nerves were completely decompressed. It was a smooth in and out operation. “I’ve never seen something so meticulously and coolly done before!” his nephew doctor commented at the end of the procedure. I was thrilled that we had managed this uneventfully.

Still, just after surgery, his blood pressure crashed. Luckily, our vigilant anaesthesia team was able to revive it without it resulting in any permeant damage. As expected, he took a little while to wake up after we removed his breathing tube. But when he woke up, he said he couldn’t see anything, and his right eyelid drooped a little, complicating things even further. I was devasted. Instead of restoring his vision, I had made it worse. All my joy and thrill of pulling off what seemed impossible came crashing down. An urgent scan of the brain showed that it was clean. There was no bleeding or pressure on the nerve from any residual tumour; that meant there was no need to go back for another surgery. We reviewed the operation video to see if we had inadvertently damaged something. At no point did the family say anything. “Acceptance is a small, quiet room,” I remembered American author Cheryl Strayed saying.

We waited a few hours. I prayed a little. Then a lot. After I finished seeing patients in the OPD, I went back to check on him. He could now see clearly with his left eye. The next day, the vision in the right eye also returned, but the eyelid was still droopy. There must have been some swelling around the nerve that had caused this to happen.

It was his wife’s birthday that day. She had sat there by his side, immaculately dressed in a saree, just a year younger to him. “We’ve been married more than 75 years,” she told me as she fed us cake. “What’s the secret to a long and happy marriage?” I asked. “Patience and faith,” she replied promptly. “I wasn’t worried yesterday when all of you were running around wondering what’ll happen with his vision,” she spoke stoically. “Everything good takes time,” she told me in Gujarati.

With each passing day, Babulalji’s vision got better. He regained the strength to walk on his own. His entire family were delighted with the outcome. I told them it was a team effort, especially because of the anaesthetists who were able to pull this off, and his granddaughter agreed. On the day, he got discharged, I asked him how he was feeling. He insisted I run my hand over his head a few times. He clenched both his fits, thumped them in the air, and shouted, “I’m the happiest man in the world!”