“Mazda, you have to speak at the Global Tipping Point Summit,” Coomi called to tell me in her usual erudite fluency that reminded me why Parsis are the direct descendants of the Queen. She was in the process of conceptualizing a comprehensive event to revolutionize the future of education. “We have to create healthy learning and nurturing ecosystems by combining knowledge with self-awareness and wisdom, to transform our lack-based consciousness to one rooted in abundance,” she went on eloquently, making me realize she she’s not only related to the Queen but also to Shakespeare.

I’m very drawn to people who are passionate, and Coomi Vevaina is not only an ardent and internationally acclaimed educator but also a faithful futurist. She’s a vivacious storyteller and has written loads of books on children’s education. “We have learnt more about the human brain in the past five years than in the previous hundred,” I explained, “and I think it’s time to bring the evidence provided by neuroscience into the classroom. We can talk about neuro-education,” I agreed enthusiastically. If you want to sound super-intelligent about anything, just prefix it with ‘neuro’. One can even get away with being sexist by calling it neuro-sexism. After training for 9 years in South India, all I learnt of the language was neuro-Tamil.

The human brain has about a hundred billion neurons that make a complex network of about a trillion synapses. From their interactions with each other emerges a whole spectrum of abilities that we called human nature and human consciousness. It is this consciousness that everyone is suddenly so interested in tapping into. The brain weighs only 2–3% of one’s body weight, yet consumes over 25% of its energy; more electrical impulses are generated in a single day by one brain than all of the cell phones in the world.

In the talk I gave at the Summit, I went on to explain how students and teachers are not uniform raw materials or assembly-line workers but a diverse collection of living, breathing human beings with complex evolutionary histories, cultural backgrounds, and life stories. If we are to move forward, we must admit that a one-size-fits-all model of education is doomed to fail the majority of students and teachers. We have to tap into the individual potential of each child and cater to their strengths. Just like we have evolved in precision medicine, we must in precision education.

Human beings have undergone an evolutionary change over the last 30,000 years and will continue to do so. With this current generation, our craniums have become larger and the sockets of our eyes bigger, which probably has something to do with the information overload that comes our way each day. Just as dendrites get chopped, churned, and pruned when not used, or as new connections form when we develop a new skill, learn to play the violin, or master a foreign language, our physical structure is also undergoing a metamorphosis governed by the external stimulus we interact with constantly.

What do we know about the brain that we did not know a few decades ago? Neurogenesis. While most of the neurons are formed at birth – and it was once believed that we only have a fixed number to live our whole lives with – we now have evidence that we can generate new neurons in those areas of the brain that represent learning, formation of memory, regulation of emotions, and spatial navigation. Everything the doctor’s been telling you – eating less, exercising more, replacing saturated fats with omega-3 fatty acids, being mindfully less stressed, and getting more sleep – promotes neurogenesis.

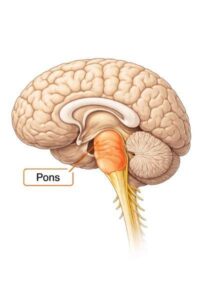

There is also the concept of neuroplasticity: the ability of our grey matter to thicken or shrink, improve connections between neurons, create new neurons, and destroy old ones. Parts of brain function can be transferred to other areas of the brain and even hemispheres can switch function. When we perform epilepsy surgery, for example, we can disconnect one brain hemisphere entirely from the other; the functioning half then works effortlessly overtime, seamlessly taking over entire brain function.

I once had a patient who had a tumour in the left temporal lobe, one of the language areas. She had a seizure, which is how the tumour was diagnosed. Interestingly, after the seizure, she switched her choice of language from native Marathi to fluent Hindi – something she hadn’t spoken at home for 2 decades. A few months after surgery, she returned to Marathi harmoniously. It has to be said that while these are the patients who are supposed to help us study brain structure and function better, end up confusing us even more.

We are gifted to be alive in an age of technology, to have decades of research in brain function behind us, and to have increasing data-based interventions associated with improving the health of our children or to realize that age-related cognitive decline may be slowed, arrested, and even reversed.

We have studied the importance of art, music, movement, and storytelling in the overall development of children. As part of the action project of this summit, we aim to study if we can simulate an objective response in children by systematically introducing these paradigms into their curriculum’s. The art of education is more important than any other, as we are forming souls and shaping the future of humanity. Interestingly this conversation will be carried on at the Global Tipping Point Summit: Re-thinking Parenting from 8th to 31st January, weekends only (from 4 to 5.15 p.m.) and people can join us for free by registering on www.gtps4change.org.

Neuroscience teaches us that story telling can impact the brain in innumerable ways. It releases oxytocin and teaches children to empathize. It activates mirror neurons, which is said to have shaped civilization. Stories can ignite ideas. They can stir up feelings of awe, wonder, inspiration. They can make us jump out of our seats in surprise or terror. Stories hold powers greater than we may have imagined. “Stories are memory aids, instruction manuals and moral compasses,” says Aleks Krotoski.

But more than the stories we tell our children, we should take time to reflect on the stories we tell ourselves. Like Carl Jung said, “The most important question anyone can ask is: What myth am I living?”