To do the surgery or not? A surgeon is faced with the conundrum twice in the last two months and takes home different lessons

In the past two months, I operated on two patients who didn’t need surgery, or so I thought. But this is not one of those stories giving credence to the popular public opinion of doctors advising surgical interventions to patients who may get well even without them. This is deeply complex, emotional, and heart-wrenching. Greed, money, power, and ego have no place in stories battling life and death, where hope and faith combat the eternal question of where one draws the line of acceptance that the end is near – the most difficult and the most beautiful conundrum in simultaneity.

The first patient was a lady in her sixties. She had had two previous surgeries elsewhere a few years ago for a malignant brain tumour, followed by radiation and chemotherapy. In the past week, her health had deteriorated. She was in a semi-comatose condition, partly paralysed in her left arm and leg. Her husband and son had done everything they could have over the past 5 years to keep her going – taken her for opinions abroad, administered targeted therapy beyond regular chemotherapy based on the genetic analysis of her tumour, and enrolled her in an experimental wonder drug trial. “The tumour has returned, this time even more vociferously,” I told the family, who came to me with her reports while she was admitted at another facility in the ICU on a ventilator.

Their oncologist, who had primed them that further surgery may not help, sent them to me for an opinion. After carefully peering through sheaves of reports, I told them, “We can remove the tumour, but I don’t think it’ll make her better. Her brain has taken a toll over the years, and now, it is best we let her be,” I said, convinced that further surgery may neither improve her survival or the quality of it. “But we’ll never know if we don’t try,” her son rightfully reasoned, knowing that their herculean efforts had already prolonged her survival beyond the average expectation for a glioblastoma by 3 years. “We understand all the complications and everything that can go wrong, but you’ve come highly recommended, and we’d like you to operate.”

These are statements that flatter a surgeon’s ego, elevating us onto a superior realm, making us feel invincible. Most surgeons know how to put these words aside and focus only on the patient and what’s best for them. But even amongst surgeons, opinions are divided: Some physicians argue that a patient who will not benefit from surgery should not be operated upon, and will vehemently oppose any such request from the family, no matter how much they plead, while others argue it’s our duty to do the best we can as long as the intention is to help the patient, with full disclosure to the family that even the contrary might happen. No matter which set we belong to, all of us know that if the family insists on an operation, it is because they don’t want to bear the burden of guilt of not having tried enough for a loved one.

“Okay, I’ll do it,” I said reluctantly, as we transferred her to our hospital and operated a few days later. I operated half-heartedly – because somewhere deep down, I knew I wasn’t going to get the result I wanted – but removed the tumour fully. After surgery, we kept her in the ICU for a few days before the family shifted her to back to a hospital closer home, where she passed away a month later. I couldn’t help but wonder that if we hadn’t operated, it would have saved her loved ones much-prolonged anguish and several exorbitant expenses.

Within days of this patient’s passing, I was contacted by the wife of another patient of mine, whom I had operated upon twice for a malignant brain tumour. They lived in another country, and he too had surpassed the mean survival time for his brain tumour, again a stage 4 cancer. “He was well until two weeks ago, but now, gradually, he’s unable to move his left side, is slurred in his speech, and is unable to participate in any conversation,” she told me, her fear for him and for their two teenage children twisting through every word she spoke. The tumour had not only returned but spread to parts of the brain that were inoperable, and doing any more surgery had a chance of harming more than helping him. “It’s best you keep him at home and try palliative therapy,” I explained in great detail, knowing that now nothing more could be done. He was only 40 years old.

Despite this, they were on the next flight to Mumbai. I refused to operate, knowing fully well he could be much worse after surgery. “Do it for me, doc,” his wife, implored with brooding and piercing eyes. “Even a few extra months will give his children joy,” she pleaded, not allowing me to be rational. “Spend the time he has left in the condition he is in now, because he might get worse after surgery,” I urged her to understand, but she was adamant, wanting to leave no stone unturned.

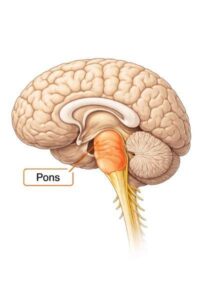

I gave in and operated on him the next day. When I opened his brain, it was tense and angry. We removed a large chunk of tumour from the frontal and temporal lobes, after which the brain seemed soft and docile. I hoped that relieving the pressure would make a difference, but the next day, he was even more unresponsive. “This is what happens when you mess with a brain that is deeply and diffusely infiltrated by tumour,” I told his wife, subconsciously trying to cut myself some slack. The next morning, there was still no change. “I don’t think he’s going to make it,” I told her, but we continued making every effort in the likelihood that he would.

The CT scan wasn’t alarming and the EEG did not show any abnormal activity, which made it all the more puzzling that he wasn’t waking up despite a nicely performed operation. Three days went by with no sign of improvement. I cursed myself for not having learnt from the previous case. In my defence, I had laid all the cards on the table, but I also know that deep within there is a moral obligation that a doctor has first to himself and then to his patient – and I was unable to decipher if I had violated it.

Every day as physicians, we are battling decisions of right and wrong. On most days, the answer is simple, but on some days, simple is hard. Oftentimes, spine surgery gets a bad name because of contrasting opinions from varying surgeons: While one opinion might be to have urgent surgery, the same patient might be advised to wait it out by another surgeon, leaving patients confused and suspicious of doctors. But the truth is, every now and then, there is no right answer, and despite having made prodigious progress in medicine, we have to admit there are many things we still don’t know. “Keep the company of those who seek the truth – run from those who have found it,” discovered Vaclav Havel after a lifetime of searching.

The next day when I went for my rounds, dreading to see him and give the same bleak news to his wife, he surprised me by showing up wide awake with almost a sparkle in his eyes. To my surprise, he was even moving his arms and legs well. A few days later, we were able to pull out his feeding tube and he started eating on his own. By the end of two weeks, he was swift and coherent and flew back home to a smiling family. She sent me pictures of their kids hugging their father. How long he has left is nature’s call, but for the time being, his wife’s call stood tall. Maybe after all, in their context, he did need that operation which I had deemed futile.