Glossopharyngeal neuralgia causes pain sudden and severe enough to feel like a phataka go off in your mouth. Awareness about such rare conditions is half the battle won

Mrs. Pednekar walked into the clinic with her husband. They looked like they were both in their sixties. Simple, warm people dressed in pastel shades, they joined their hands in a namaste with bowed heads as they took their seats. “My husband has been in severe pain for the past 10 years,” she told me, her eyes welling up almost instantly. We often see patients break down in the doctor’s clinic within a few seconds of their arrival, even with little being already said or done. I imagine the office seems like a portal where they feel they can release that pent-up angst, anxiety, or energy.

I allowed for her to feel soothed and then continued. “Where is the pain?” I enquired. “In the left side of the throat,” he said, his entire face clenching in a tumultuous spasm simply with the utterance of those three words. “He cannot talk, eat, chew, or swallow when he gets these random bouts of pain multiple times a day – and it’s been several years now,” his wife continued, allowing for his electric shock-like sensation to settle. “But in the past three months, it’s become unimaginably unbearable. He’s lost 12 kilos because he fears eating will trigger a spasm,” she concluded.

“It feels like I have an entire loom of firecrackers bursting in my throat randomly,” he explained once the episode settled. “Well, with Diwali around the corner, you’ll be able to have an internal celebration!” I quipped, wanting to ease the situation and trying to be my usual self, which they understood, but they also wanted me to fathom the magnitude of the problem. “Doctor saab, it’s not funny,” he cautioned with one hand, ready to grasp his own throat if a cracker burst inside. “Imagine you’re fast asleep and someone stabs you in the throat,” he paused, trying to provide another analogy. “Several times over,” he continued. “Every night, many times a night,” he stressed. “You’d rather wish you were dead, but you wake up like a ghost wondering how come you’re still alive,” he stopped with a precise description of what he was feeling. I was now confused if it was Diwali we were celebrating or Halloween.

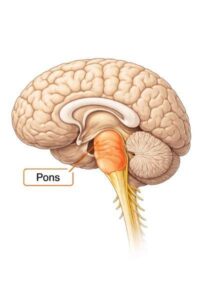

“We’ve been to so many doctors and taken so many medications and injections that our pain specialist finally referred us to you to try surgery, as they’ve run out of options,” she said as she handed over the MRI films to me. Like I had expected from my clinical assessment, it showed an artery at the back of the brain pressing against the glossopharyngeal nerve, the nerve responsible for sensations in the throat, or what is technically called the pharynx. Sometimes, an elongated piece of the mastoid bone called the styloid process can also cause the same sensations, but he didn’t have that. “When this artery pulsates, its pressing against the nerve and causing this lancinating pain,” I explained to them, adding that as they had tried everything, surgery would be a good idea.

“We’re prepared to get admitted today,” the wife said, clearly unable to see her husband suffer any longer. I adjusted my surgical schedule to accommodate him so that they could check in the next day. Unfortunately, in a preoperative workup for surgery, his echocardiogram showed very poor heart function. “Do you get breathless while walking?” I asked when I saw him on rounds the next day. “Very,” he said. “He’ll need an angiogram of the heart before we can proceed with surgery,” the cardiologist opined, which he performed the same evening.

We sat down again with the family to explain the situation to them. “He has three very severe blockages in the heart,” the cardiologist said, “and needs three stents or a bypass surgery, but if we do that, he’ll have to be on blood thinners and we’ll have to defer the brain surgery to at least 3 months later,” he opined. “If we go ahead with the surgery without the heart procedure…?” the wife asked. “Then there is a very high chance of having a heart attack during surgery,” he completed the sentence for her. “Plus, during this operation, one can have sudden changes in heart rate and blood pressure because we are very close to the brainstem,” I added for them to fully understand the risks of going ahead with surgery in this state.

“I’m willing to die, but I can’t live with this pain,” he said with a certain degree of authority. “You’ll have to sign a consent form that you’re aware of and accept the possibility of there being a death on the operating table,” I said to sheepishly safeguard myself, but knowing that there is a higher force that understands that we were all working in the best interest of the patient. He signed on the paper and his wife countersigned it. They say that when your intentions are pure, nothing horrible will happen. Unfortunately, I have lived and worked enough to know that this is not true.

The next day, we took him into the operating room. His wife stood outside with hands folded. “Everything will be okay,” I reassured her, as I do with every relative before walking into the operating room. We positioned him sideways to make an incision behind the left ear and made a coin-size opening into the back of the skull to get to the artery that had ensconced the nerve so intently. It looked like a cobra that entwins its prey before killing it. As we separated the artery from the nerve, gently untethering the silvery strands attaching the two together, the heart rate suddenly dropped to 50, then 40, then 30, as the alarms went off. “Stop whatever you’re doing!” the anaesthetist alerted.

The moment I released my instrument from the tug it was creating on the brain stem, the heart rate bounced back up. We tried again to gently release the artery but the heart rate crashed once again. “This could strain his heart,” the anaesthetist warned. “We have to release this completely,” I said, “or we won’t do him justice,” I requested them to hold fort. After multiple attempts and a few heart attacks myself, I was able to free the artery completely from the nerve. We inserted a piece of Teflon padding to keep the two apart. Thankfully for him, he survived the operation and was delighted to realise he was pain free within a few minutes of waking up.

“I wish someone had told me that surgery was an option 10 years ago, I wouldn’t have suffered so much,” he said with relief and lament together, the next morning, when I went to see him. I explained to him that it was unfortunate that people are still unaware of such conditions like glossopharyngeal neuralgia, as it is quite rare, but awareness is gradually increasing. I told him he should thank his pain doctor for setting him on the right track.

Three days later, the cardiologist inserted an equal number of stents in his heart, giving him a complete overhaul and getting him ready to be discharged. “Now that your pain is gone, you’ll have to burst real crackers,” I took the liberty of joking again. “I’m not going to burst any crackers, doctor saab,” he said with folded hands, “but every night for the rest of my life, I’ll light a diya for you and your family,” his eyes welled up. “Happy Diwali,” we uttered in simultaneity as we hugged each other goodbye.