The tumultuous emotions witnessed during the FIFA World Cup final is the everyday story of a surgeon

I must confess that while I’m not a big football fan, I jump onto the bandwagon once every four years and watch the last few matches of the world cup. And what an eclectic final we witnessed! Probably one of the greatest world cup matches ever played. Every conceivable emotion that humans are capable of experiencing came alive in a span of three hours across the globe. Joy, sorrow, hope, fear, and passion were not just simmering but boiling in the same pan. Devastatingly beautiful. The certainty of Argentina’s success was transformed almost irrevocably in a matter of minutes by the French. However, the exuberance of Mbappé’s youth was eventually silenced by the resilience and wisdom of Messi’s experience.

The morning after the dust had settled, I couldn’t help but think about the similarities between soccer and surgery. It’s a different thing that when soccer players end their careers, surgeons start theirs, but every surgery performed on the brain (if not spine) is like a football match – if not always a final, definitely a knockout. It’s you versus the tumour. Only one can win.

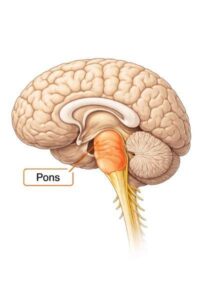

You need to know when to attack and when to defend. You need to find the correct corridor and get to the tumour without conceding a foul to a neighbouring blood vessel. Unlike in football, in neurosurgery there are no yellow cards, only red ones; one mistake and you’re out of the game, and there’s certainly no referee to argue with save for God. An operation is indeed akin to a football match. For most of the game you’re passing (instruments) and occasionally you’re dribbling (as some of the instruments need to be controlled by foot). There are many, many minutes of boredom and a few moments of terror. Like in football, it is those moments of terror that test your grit and grace.

Younger surgeons (the Mbappés), having just learned all the skills in the game, are often more aggressive. They walk into the operating room with their chests popping out; they have the brashness of a footballer and attack a tumour by destroying everything that comes in their way. This pugnacious attitude often works, and is, in fact, needed in the right dose, but overdoing it might harm both the player and the team.

Tempered surgeons (the Messis) know when to pick their battle. They’re gentler with tissue, and take their time to dissect and attack in short bursts when time and space is on their side. This makes them surer and more efficient even though it may seem like they may take longer to complete the task. They know how to get themselves out of trouble, something that comes only with the wisdom of experience. Like the famous surgeon and writer Atul Gawande says, “The difference between triumph and defeat, you’ll find, isn’t about willingness to take risks. It’s about mastery of rescue.” Good doctors and hospitals don’t fail less; they rescue more. Argentina were able to rescue themselves from where they were. There was a certain cockiness about France when they thought they had the win in the bag.

Taking a penalty is like removing the last bit of tumour stuck to an important artery or nerve. At that given instant, everything you’ve trained for all your life becomes important to the solution of the problem. You can’t do it later. You can’t scroll down on your phone for help. You must have the exact precision, speed, and timing for that one move. Your heart is racing beyond measure and yet your hands must be still as a rock that is oblivious of the raging winds. Everyone is watching what you’re doing on giant monitors in the operating room amidst the deafening silence of beeping monitors. Either you score or you are annihilated. And both those things can happen in the span of one operation. The emotions we witnessed in the world cup final are those that surgeons experience regularly, but thankfully, they aren’t broadcasted live on world television.

Oftentimes we score, but sometimes we stand defeated. And when we lose, we too cry like grown up footballers, but it happens in the isolation of our closed spaces. We don’t have people telling us it’s going to be okay. Like the famous surgeon René Leriche (it’s not a coincidence that he was also French) said, “Every surgeon carries within himself a small cemetery, where from time to time he goes to pray – a place of bitterness and regret, where he must look for an explanation for his failures.” Every footballer probably does the same for every penalty they miss. Every sportsperson does that for all the chances they lost. Michal Jordan once said, “I missed more than 9000 shots in my career. I’ve lost almost 300 games. 26 times, I’ve been trusted to take the game winning shot and missed. I’ve failed over and over and over again in my life. And that is why I succeed.” And that is what Messi showed the world on that fateful Sunday. That is what surgeons across the world do when they go out each morning like gladiators stepping into the arena. “Neurosurgery is a contact sport,” the famous aneurysm surgeon Juha Hernesniemi once told me.

As we draw closer to the end of another glorious year, most of us sit back and reflect on our hits and misses, wins and losses, triumphs and disasters. We deliberate on where we went wrong and what we need to do to course correct. We forgive those who hurt us and seek forgiveness from whom we have harmed. We strive to take the next small step in the right direction. We hope that in the coming year we will be a better, stronger, gentler, and kinder version of ourselves.

We wish that each of us eventually has a story to tell, because as Gawande says, “Life is meaningful because it is a story…and in stories, endings matter.” Just like it did for Argentina and Messi.

I hope the end of 2022 allows you to start a new beginning. Here’s wishing you all a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year.