When a surgeon plays snake charmer, a young African man is freed from violent seizures on the other side of a perilous surgery

Tom arrived with his mother and brother from Malawi, a small country with a big heart in the eastern part of Africa. Unfortunately, it is also one of the poorest countries in the world, ranked 174 out of 193 countries on the Human Development Index. India is at 134, in case you were curious, while Switzerland is at the top.

“They do not know what to do with him back home,” Tom’s mother said, telling me of the occasional sudden jerks in his left hand and leg. “He just starts shaking like a machine gun out of nowhere, and the last time this happened, he spat out blood,” she told me, a little shaken herself from the anxiety that enveloped her. I explained to her that her 18-year-old son was having seizures or epileptic fits, and that the blood that had emanated was probably from a tongue bite. “I also have headaches,” he interjected, pointing to the right side of his head from which tiny curly hair sprouted. The CT scan they had brought with them showed “something” in the right frontal lobe, but it was too grainy to decipher; it was like a bad screenshot from a monochrome movie in the 1950s. “We’ll get an MRI to ascertain what the exact problem is and take it from there,” I announced, as we started medication to control the jerks.

I am amazed how we still live in a world where people have to leave the safe confines of their hometown and travel across continents for advanced medical aid. Patients who come to South Bombay for treatment from Goregaon may be able to relate to it.

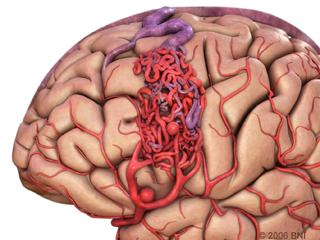

The MRI revealed a 5 cm arterio-venous malformation. “There is an abnormal tangle of blood vessels between the arteries and veins disrupting his blood flow and oxygen circulation, which is why he’s having headaches and seizures,” I explained to his mom, who seemed like she was going pale, but because she was African, I couldn’t really be sure. “Because these blood vessels do not form properly, they can even rupture to cause a brain haemorrhage,” I cautioned as she sat down with a thump, while the younger brother was playing video games on his phone, least affected by the drama in the room. I added that oftentimes, people don’t know that they are harbouring such a malformation until it starts bleeding inside. He was lucky that catastrophe hadn’t struck yet for him.

“Why do these things happen, doctor?” the mom asked after adequately composing herself. I resorted to my standard template for most questions in medicine – “Nobody knows!” – but went on to explain that it could have a genetic predilection. Maybe I should have said it comes from too much screen time; the other brother might have then paid some attention. “We have to remove this,” I suggested, after studying the angiogram we got done subsequently. Despite her fragile state, I went on to enlist all the possible complications that this surgery could entail, albeit lovingly. “These operations are long and difficult,” I added, “but we’ve done many of these with good results,” I reassured her. She gave me a big, famous Malawi smile. “Do your best, doctor!” Africans are kind and trusting. In my opinion, it is the most soulful continent on the planet.

The next day, we made a large C-shaped incision over half his skull and removed bone the size of a saucer. We opened the covering of the brain, the dura, along the edge of the bone and saw this arterio-venous malformation gnawing at us, resembling a bunch of violent, convoluted, magenta and fuchsia snakes hissing angrily at us once their bamboo basket had been opened. The surgical challenge was to extricate this serpentine leash without being bitten. This was a complex task because some of the arteries that feed the malformation also supply normal brain tissue, and oftentimes, it is hard to differentiate between an artery and a vein as their blood is mixed. In these malformations, the normal capillary network is missing, and hence the pressure in the system is very high. You buzz the wrong vessel, and the malformation will blow up in your face, akin to being walloped by a python.

We meticulously meandered around the periphery, terminating all the baby snakes first from the surface and then gently from the depths, without waking up the mother snake. Oftentimes, there would be angry spurts of blood that needed to be controlled with equal aggression. I was the predator disguised as the snake charmer, but my pungi was not mesmerizing them with music but violating them with vehemence. One by one, we decimated over two dozen of these snakes until the last one gloated with pride. I held it between the tips of my forceps and charred it to death, disconnecting it from normal circulation. A great ball of fire was now a scalded bird’s nest. The crimson African sun was doused before the sunset. We removed it completely and waited for a while to ensure there was no further bleeding before we closed. “These malformations are notorious for bleeding even after surgery,” I told my team to keep sharp vigil as I left the operating room, allowing them to close.

Tom’s mother was thrilled to see him in the ICU fully alert and talking well with no neurological dysfunction. But just when I was about to leave for the day, the ICU called saying he had had a seizure. Not only was he shaking but he was also not responding. Luckily, he regained consciousness in 7 minutes. A CT scan came out clean, with no snakes spitting venom. We hiked up his anti-seizure medication. Two hours later, he had another seizure. Something in my gut told me to repeat a CT scan. This time, it showed a significant amount of blood at the edge of our resection cavity. Luckily, it didn’t need going back to the operation theatre because an angiogram confirmed we had removed the entire nidus.

We ventilated him overnight, while his mother played some Bible music in his ears. The next morning, the African sun rose again. Bright and cheerful. In all its glory. We were able to shift him out of the ICU and got him to eat, walk, and be free again in a few days. “Now we know why no one in the entire country wanted to do this operation!” the mother told me. I told her how challenging these cases could be and gave her the snake analogy. “Did you know there are 66 different kinds of snakes in Malawi, 24 of which are potentially deadly?” the zoology teacher in her surfaced. “There are no venomous snakes left in Malawi,” I stopped her. “We killed all 24!”

PS: No animals were actually harmed in this surgical strike.