A trying month at the hospital was a reminder of Murphy’s law—the absurd and tragic turns life can take

I’ve had a horrible month. Appalling may be a more appropriate word. Awful. Dire. Disheartening. Harrowing. Now that I have a rapt and ravenous reader insatiable for my grief, let me tell you more.

“Rajesh bhai’s wound is not looking good,” my colleague said, sending me a picture of the patient we had operated on a week ago for a malignant cerebellar tumor. He had just removed the bandage covering the incision behind the ear and found a blackish discoloration of the skin that looked ominous. I was out of the country and insisted that the patient not be discharged. “They’re adamant on going because they feel he’ll be absolutely okay,” I was informed. Rajesh bhai returned two weeks later with the wound gaping and smelling as if a rat had died inside his head. “We’ll have to take him back to the operating room and clean up the debris,” I insisted. The family acquiesced, knowing that if they had listened to begin with, we would have been able to avoid this entirely.

“Something as simple as a little extra pressure from a bandage can cause trouble like this, so let’s be really careful while cleaning up this wound,” I cautioned my team on the importance of doing the small things well so that the big stuff can be taken care of. “Murphy’s law, boss,” my colleague told me, reminding me, “If anything can go wrong, it will.” I understood what he was saying: However much we take care, sometimes things are not in our control. “Have you heard the corollary to that?” I asked him. He shook his head. “It’ll always go wrong with the worst possible outcome at the worst possible time!” I taught.

The day Rajesh bhai got discharged with a healthy looking wound, we breathed a sigh of relief. The family thanked us for going out of our way to do what we’d done despite their having dismissed our advice initially.

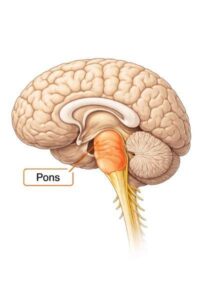

That morning, we had just finished surgery on Charles, who was experiencing intractable facial pain. The surgery went off impeccably and he woke up pain-free, hardly able to control his excitement that he was absolved of years of agony. A routine CT scan done after surgery was clean. A few hours later, he started thumping his chest and walking around his room as if he were possessed. His blood pressure shot up to over 200 and he sustained a fatal brainstem hemorrhage. Before we could do anything, he was dead. I was unable to explain to the family that a man who they had been speaking with a few minutes ago was no longer alive. “Mother nature is a bitch,” Murphy said.

We had operated on Lalitaben a few days ago for spinal compression, which we relieved with surgery. Her sciatica resolved well enough for her to start using the washroom independently. One foggy morning, she slipped in it and fractured her foot. This needed a caste. She had come to the hospital limping on one foot and now tarted limping on the other. Her leg pain returned because of the pressure her back was subjected to from unequal load bearing. I advised her to rest it out and that it would hopefully resolve itself. “Everything takes longer than you think,” I reminded my team of Murphy again.

“Why is this happening to us all of a sudden after going through the entire year with no glitches?” I questioned my colleague. “Karma!” he replied. “Whose?” I asked. “Mine, yours, or the patients’?” “It’s always collective,” he reminded me. “It’s nature’s way of keeping us grounded,” he justified.

Just as I was recovering from the heartbreak of these three storms, Joanna’s mother called from Africa. One month ago, we had removed a bony overgrowth from the base of Joanna’s skull through an incision in the eyebrow, a neat and easy surgery. I was so proud of the operation I asked my friends to guess which eye brow we went through, and they couldn’t make out. But today, everything was different. “She’s leaking brain fluid through the nose,” her mother said, panicked, “and the doctors here are refusing to treat her!” The leak was hard for me to fathom, as we had not opened the dura – the layer that protects the brain and contains the fluid. “If the fluid gets infected, she could die,” I told her over the phone. She was just 18 years old. “Fly her down back to us, flat in bed,” I instructed, and they obeyed. When I saw her, cerebrospinal fluid was leaking from the nose as if someone had left a tap open inside her head.

We re-operated on her to find a 5 mm hole in the dura from a bony spicule on the undersurface of the bone rubbing against it. We repaired it and sealed the defect. We made her sit up after a few days and she was fine. “Nothing is as easy as it looks,” Murphy reminded us; we’d considered this to be a simple operation initially.

The ongoing challenge in a life of surgery is how to maintain outward confidence and stoicism in the face of internal cataclysm and upheaval. How to yearn for an inner stillness amidst extraneous cacophony. How we make loss a reason to live more deeply. Maybe Kipling had the answer when he said, “Hold on when there is nothing in you except the Will which says to them: ‘Hold on!’”

And just when I thought I had paid my debts, earlier this week, we operated on an elderly man for a brain tumor. It was a beautiful operation, done in the most pristine manner. He woke up well after surgery, but as he was being wheeled into the ICU, he stopped breathing. We had to resuscitate him and shove a breathing tube down his throat to protect his airway. The CT scan of his brain did not show any cause for concern. There must have been some swelling in his vocal cord that obstructed his airway, the anesthetist opined. The next morning, we were able to extubate him and shift him out of the ICU, where he continued to recover for two days. He was soon his usual chirpy self, cracking old uncle jokes. But as Murphy says, “The light at the end of the tunnel is only the light of the oncoming train.”

The next day, he had a seizure and turned drowsy. His neck was stiff and he’d developed meningitis – a florid brain infection; we confirmed this by sticking a needle in his back and drawing some spinal fluid. Murphy had reared his ugly head yet again. We gave him a high dose of antibiotics and he seemed to start recovering. “I fear this may take time,” I told the son. “The more you fear something, the more it’ll happen,” whispered Murphy. “We trust you, doctor,” the daughter said as I exited the ICU. I wasn’t sure if I trusted myself anymore.

December, please be kind. And screw you, Murphy! Because as my friend Ab Lincoln says, this too shall pass.