The unreal real story of a couple separated and united by one of the world’s worst tumours there is

Sam and Anita sat in front of me in my clinic. They were a couple in their early forties. He was a gym instructor and she was a teacher. Their physical appearance said they had little in common on the outside. They looked like the king and queen on opposite sides of a chess board, but were on the same team in life. Seeing them I realized that true love sees no caste, creed, religion, or race. After I heard their story, I figured, cancer doesn’t either.

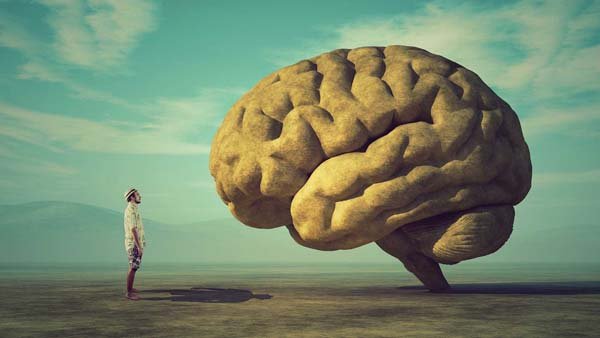

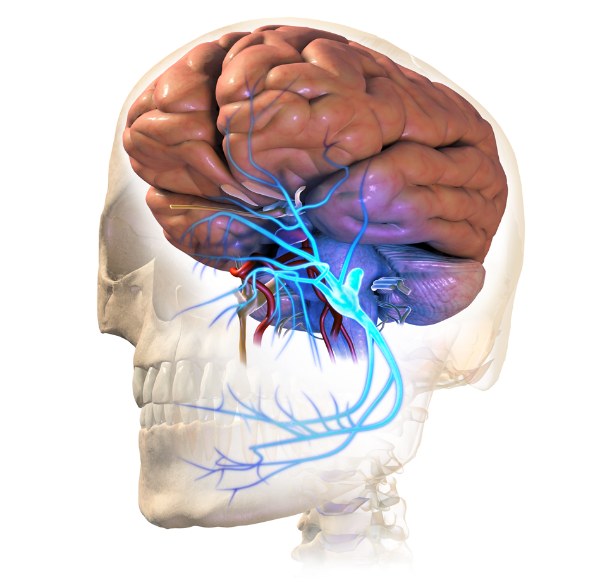

“Sam was diagnosed with a glioblastoma in his right frontal lobe a year ago,” his girlfriend started, holding his hand as she spoke, while I noticed his eyes welling up with silent tears. A glioblastoma is grade 4 brain cancer. It is a ghastly diagnosis to live with. The median survival of this tumour is 1–2 years. “He had surgery by another surgeon and followed it up with 34 fractions of radiation and 6 cycles of chemotherapy,” she gave me the lowdown. The previous surgeon had done a perfect job with interim scans showed an immaculate resection and a wonderous initial response to therapy, but as expected in these ghoulish tumours, it had recurred.

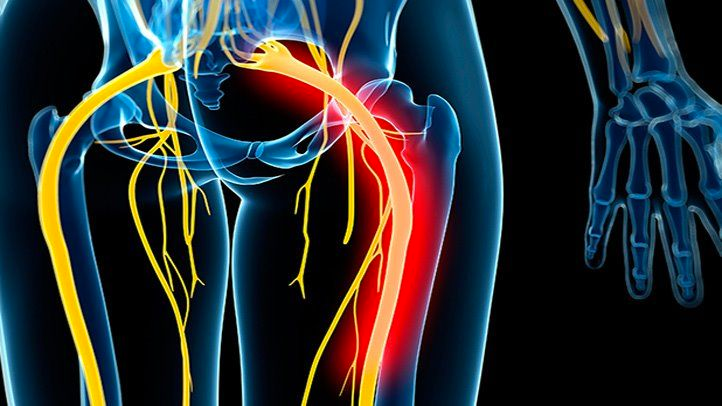

“For 2 weeks, I noticed I was dragging my left foot and finding it hard to button my shirt,” he described, getting up from his chair to show me his gait. “That’s when we repeated an MRI and found that it had all come back,” Anita continued. I examined him to find his left arm and leg slightly weak. As I peered through the MRI, it showed a large growth in the right frontal lobe that was pushing against the motor cortex, thus responsible for his weakness. It had also spread to the opposite side through fibres that connect the two halves of the brain. “The tumour’s not only come back, it’s done so with a vengeance,” I announced. “We know,” they said in unison, a gnawing sadness permeating the room.“Our previous surgeon simply said, ‘Nothing can be done about it.’”

I recalled those being exactly the same words a dermatologist had used for me the previous day when I’d asked her if something could be done about my premature balding, but I didn’t think it right to mention this at this time even though I have always believed that honesty and humour are the two greatest weapons in the face of helplessness. She had also advised me to ‘accept it gracefully’, and I wondered if that, perhaps, would be the appropriate thing to say here. They were an empowered couple who had done their research and were fully aware of the finality of this diagnosis. “You could do more chemotherapy or attempt another surgery, but I’m unable to assure you or confirm if this will alter longevity and improve the quality of your life. Sometimes it could make you worse,” I said, agreeing with the previous surgeon.

“We have a date to get married in three months,” Anita said, looking into Sam’s eyes, surrendering to the anguishing anxiety of an uncertain outcome. These are such deeply personal choices that I refrained from making any comments, although I did briefly wonder why she wanted to marry a dying man. “We’ve been dating for 8 years, and a few weeks before my diagnosis, we’d set this date. We want to go ahead with it,” Sam said with a depth I was unable to fathom. Who among us would have the will to marry someone we know is going to die shortly thereafter? The answer to most things comes in not looking for one.

We discussed all the technicalities, and much to my reluctance, I agreed to another operation; I couldn’t help but remember it was Voltaire who said, ‘Every man is guilty of all the good he did not do.’ I had to keep any personal judgement aside because if we didn’t operate, I was pretty sure he wouldn’t make the date.

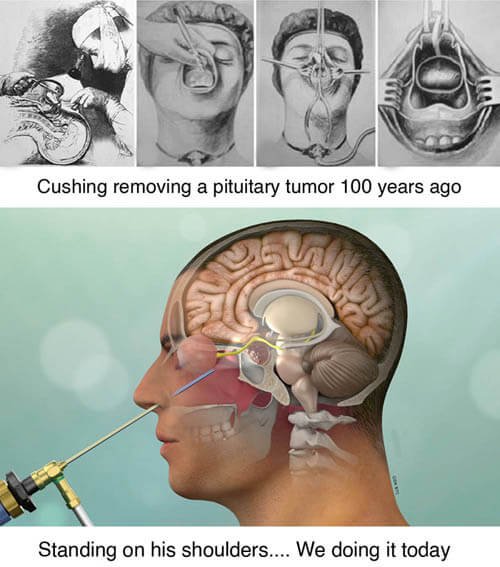

A few days later, we opened up the right side of his head. Everything about this tumour was macabre. It was dark and ugly. The veins in it had thrombosed and there were pockets of necrosis or dying tissue. There were engorged arteries feeding the tumour with the blood haemorrhaging in its core, which I buzzed and cut, buzzed and cut, and buzzed and cut again.I kept removing it until I saw some semblance of normal-looking brain around, ensuring I had relieved the pressure on his motor cortex. The monstrosity was demolished, and the brain once again looked illuminatingly beautiful under the brilliance of the microscope. We had restored some normalcy and hoped we had added a few checkered days to the duo’s black and white lives. He woke up the next day with improved arm and leg function, but I was unsure of how long that would last. We scheduled him for some more chemotherapy as he got discharged. “We’re going to go for a holiday before we start chemo,” Anita smiled, giving me a hug to say thank you. They had transformed their suffering through their irrepressible vitality of spirit.

Cancer has been around for centuries. We have done so much to find a cure and yet, in the larger scheme of things, it has proven to be so little. It indeed is a great leveller. It respects nothing. But recently, I came across some research that elephants don’t get cancer. The answer is, at least partly, that elephants’ cells have an astounding 20 copies of p53, a cancer repair gene. Humans just have 1. In a world where we see everything in black and white, it sometimes helps to be grey. “The war against cancer,” noted physician and writer Siddhartha Mukherjee in his epic novel – The Emperor of All Maladies “continues to oscillate between being profoundly distressing to relentlessly exhilarating.”

Three months after they were discharged, Anita sent me enraptured photos of them at their Bali destination wedding. She was dressed in bridal silver. He wore adark tuxedo. They were amidst flowers and friends of a myriad hues and glows. They were singing and dancing and living their dream. Several weeks later, I heard from her again. He hadn’t made it. Everything once again was back and white.