In a world where you can be any kind of parent (helicopter, dragon, tiger, dolphin) – some parents just simply choose to be entertaining.

I have two daughters, one each in the first and second grades. They go to school by their school bus, a convenient way for them to travel, and that is more than enough for me. But if you go by the WhatsApp chats of their respective class groups, it is clearly not enough for some of my fellow parents. These chats are also the sole reason for my phone reaching its maximum storage capacity thrice a day.

I wonder why so many parents are disgruntled with so many things. I thought that the children being out of the house for half the day – this simple fact – would bring joy to the faces of most mothers. On the contrary, from the time their kids leave home to the time they return, they are complaining about the school on WhatsApp.

The kids have a tracking bar on their ID cards that is coded to an app, which you can download on your phone to know where the bus is in transit. “The tracking system doesn’t work!” the parents moan daily. If the bus leaves 5 minutes late from school, WhatApp crashes, because the parents have no clue where their precious poodles are for those 20-30 minutes between school and home. I wonder how many children didn’t get home when these devices were not present. I remember spending a couple of hours at my neighbors’ after getting off the bus before going home. Today’s parents would freak out because the app would show that their child has reached home but is nowhere to be found!

On the days it rains heavily for a bit, some parents will send photos of the puddles outside their homes, protesting that school should be online that day. And if, by any chance, the school goes ahead as planned and their children’s feet get a little wet, WhatsApp starts brimming with pictures of their wet toes and crinkled ankles – the kind you’d get if you had spent an hour in the pool. “Can’t the school make provisions for the children to change into new socks? Why can’t we wear Crocs to school? How can we expect 6- and 7-year-olds to have wet feet?” they fuss. When we went to school – and it was the same school – we splashed happily in every single puddle on the way and back and no one was bothered.

“My child got bitten by a mosquito in class,” fretted one parent, and followed it up with pictures of the bite from different angles so that we, a captive audience, could get an idea of the correct amount of redness and pain. To gain some momentum, a few other parents followed this up with pictures of mosquito bites on their kids, making my WhatsApp slow down tremendously once again. Demands were made that the furniture should be checked for bugs and termites and why couldn’t the classroom be airconditioned. I was surprised no one suggested that the monsoon be cancelled. When we were little, we got cut and bruised. We were bitten and sometimes bit back. No one knew, no one cared. As long as we were alive, we were okay.

“The benches are not the right size for my kids,” grumbled some other parents. “When my child comes home, they (which, in case you didn’t know, is the correct pronoun to use in today’s gender sensitive times) complain that their back hurts and legs have cramped.” “My child can’t even do karate class properly,” bemoaned another. If everything hurts so much, I thought, then perhaps the karate class needs to be changed, not the bench. Parents are worried that their progeny, sitting on hard benches, will have osteoporosis when they grow up. I’m worried if these parents will ever grow up. I always sat on the last bench, and I have very long legs. My teachers were lovely to have allowed me to put my bench out of the class while the table remained inside; problem so easily solved.

“My child came home with some yellow paint on the uniform,” was the topic of another day. Apparently, some of the newly painted benches hadn’t dried completely. Parents objected about the school’s apparent lack of concern. “The lead in these paints is so toxic, it can affect their nervous system and cause them to have nerve problems,” was a common opinion. My WhatsApp started flickering on its own with these comments. The school was accused of jeopardizing the future potential of children who would otherwise make brilliant advances in science were it not for the stains on their uniform, the fumes from which they were actively inhaling. I didn’t complain because my daughter is in the yellow house and the yellow stains were easily camouflaged.

I had a complaint of my own, but not for the WhatsApp group. “My daughter doesn’t like to do homework with me,” I lamented to a friend of mine. She responded with, “Which child likes homework? Send her to me. Kids usually study well with someone they can’t make excuses with. I teach some underprivileged children and she can join us.” “Do you teach overprivileged children?” I joked, because our kids today are in that category. She rolled her eyes back at me. “You can’t expect to raise your children like you were raised, Mazda, because the world that you were raised in doesn’t exist,” she retorted.

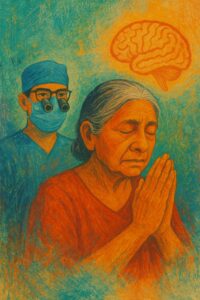

“Why do you not care about the problems these little kids face?” a bunch of parents asked me recently, when I told them about how trivial their issues were and that the school was doing a great job and my kids always come home happy (even though, on most days, they haven’t completed their homework). “Why do you live as if none of this stuff matters?” they cornered me. I mulled over that for a while, and I have an answer. I think it comes from being in the profession I am in. I regularly see children with brain tumors, hydrocephalus, blindness, and retardation. I see children with malformations of the spine, those who can’t sit, stand, or walk. I see children with epilepsy who have 5, 10, 15, 20 seizures a day. Most of these children once went to school and can’t anymore, while some of them never did. Some may not see their next summer vacation and their parents are acutely aware of it; somehow, they still smile. Where I trained in neurosurgery, in Vellore, people used to sell their farm produce, cattle, and sometimes even their homes to seek help for their children. Every time I operate on a child, I ask myself, “What if this was my daughter?” And then I’m thankful it isn’t.

So, this Parsi New Year, please, let’s not complain, at least not about the things that are paltry or inconsequential. Life is too short to be little. And so is the storage on my phone.

Happy New Year.