If the brain is the big fat joint family and the lobes are the siblings arguing over property,

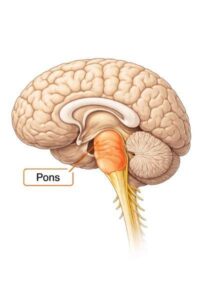

the medulla is the night-shift security guard protecting the territory. Unseen, underpaid, deeply unappreciated, but if it falls asleep, everyone dies. Unlike the cortex, which thinks, or the pons, which connects, the medulla governs survival in its purest form.

The medulla is small but savage. It does not care about your personality, your memories, or your Spotify playlists. It regulates breathing, heart rate, swallowing, blood pressure, coughing, gagging, and the rather important business of keeping you alive even when you are not paying attention. It is the part of the brain that works even when you do not – which is why operating here feels less like surgery and more like negotiating with fate.

She was in her early forties – soft-spoken, sharp-eyed, and far braver than she looked. Her symptoms were subtle at first. Occasional imbalance. A strange heaviness in the limbs. Her voice occasionally softened as if she were tired of arguing with air. The scans revealed a hemangioblastoma (a tumour of entangled blood vessels) sitting inside the medulla, glowing like a forbidden ember. Benign, yes. But in this location, benign is a polite lie.

Hemangioblastomas are vascular tumours. Think of them as over-enthusiastic plumbing projects. They bleed easily, shimmer angrily on scans, and do not appreciate being disturbed. In the medulla, they are less like tumours and more like grenades ready to blow up.

The operation felt like standing at the edge of a cliff in strong wind. Every millimetre mattered. Every movement was deliberate. We had to go around the tumour, disconnecting every feeding vessel amidst a landmine. This is where intraoperative neuromonitoring becomes not just technology but reassurance. We monitored motor pathways, sensory pathways, cranial nerves, breathing-related signals, heart rate responses. Every wire attached to her body was connected to a computer.

The tumour came out after 8 hours. A glowing red ball of fire extracted from the brainstem, coaxed out rather than conquered. When it was finally out, there was relief, followed immediately by fear. The medulla does not like swelling. It responds to irritation by sulking. And when it sulks, breathing forgets how to breathe. Postoperatively, she did exactly what we feared and expected. She did not breathe on her own.

She stayed on the ventilator. One day became two. Two became twenty. Each morning, rounds felt like waiting for a verdict. Her scans showed swelling, not damage – which is medicine’s way of saying… maybe. She was awake and able to move her limbs; she just couldn’t breathe when she fell asleep.

This is where Ondine entered the room. Ondine’s curse comes from mythology. A nymph curses her unfaithful lover so that he must remember to breathe. If he falls asleep, he dies. In medicine, Ondine’s curse refers to central hypoventilation. The medulla forgets the automatic rhythm of breathing. Patients breathe when awake, but sleep becomes dangerous. She could breathe a little during the day but quickly fatigued as night arrived.

Every neurosurgeon fears it. Every intensivist watches for it. Every family lives through it in slow motion.

And then, one month later, the medulla remembered. She started with some breaths at night. Then a few more. Weak at first, uncertain, like someone relearning a forgotten language. The ventilator settings were reduced. Then reduced again. Six weeks later, she breathed entirely on her own. No drama. No announcement. Just quiet persistence. The medulla does not celebrate. It simply resumes duty.

Six months later, she had recovered entirely. Her voice strengthened. Her balance improved. Life crept back in small, unremarkable victories. Walking. Laughing. Breathing without thinking about it.

Surgeons love big moments: tumour out, bleeding controlled, wound closed. But the real triumph here was invisible. A structure smaller than a thumb deciding not to hold a grudge.

Because the truth is, the medulla never asks for applause. It works while you sleep, while you dream, while you forget yourself entirely. And when it falters, it reminds you just how fragile independence really is.

As for Ondine, she did not get her revenge this time. Which is fortunate, because remembering to breathe consciously is exhausting. I tried it for thirty seconds.

Then I went for an Art of Living course.

1 thought on “The brainstem part 3: The Medulla Oblongata”

I’m in awe of your writing skills. And obviously a very good neurosurgeon. I can make that out, without validation form my colleagues in Mumbai.

Please continue to enthrall us with more such articles!