In surgery, and in life, it all comes down to protecting the centre.

Everything revolves around a centre. The earth pirouettes around a molten core. The solar system hums to the rhythm of the sun. Cities pulse with life arounds their downtowns. A newborn baby at a family gathering is the centre of all attraction. And in today’s context, it’s the one working charging outlet at an airport where a desperate cluster of travellers vie for their device to be the next to enter its precious electrical orbit.

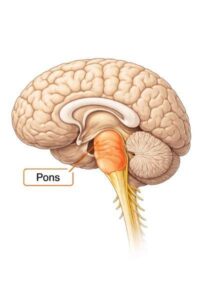

Even the brain, our crowning glory of evolution, bows to this unassuming truth – that life is regulated around its centre. Tucked deep within its protective vault rests a delicate core. Between the awakened pituitary and the sleep-regulating pineal gland lies the third ventricle ensconced by the thalamus on either side, the hypothalamus below and the union of the optic nerves guarding it – all quietly regulating sight, thirst, temperature, wakefulness, and hormonal symphonies that makes us ‘us’. You mess with the centre; you rattle the entire axis.

Akshay, a 30-year-old tall and lanky chap, much to his brain’s chagrin, housed a threat in exactly the same location. I had seen him a year ago when he came to me with dull aching headaches. The ophthalmological exam, for the so-called ‘window to the soul’, had come clean. But we neurosurgeons know better, that behind every window is a wall. And in his case, the MRI had revealed a small lesion trailing the optic chiasm, nestled near the third ventricle. Small. Subtle. Suspicious. More importantly, sentient, which I found out only after a year of watching it grow slowly but consciously. Due to the criticality of the location, him being relatively asymptomatic, and the possibly benign nature of the lesion, I had refrained from offering an operation. But now it was pushing against the optic chiasm, threatening to steal his sight. His sleep was a bit disturbed. He wasn’t eating well. The centre was misbehaving. And that’s the thing about central problems: They start quietly but rarely stay polite. We had no choice but to turn to the heart of our craft.

“What is the risk of this surgery?” he asked. “The tumour is smack in the centre of your brain,” I explained, detailing the anatomy lodged between hope and horror. “Anything can go wrong,” I surrendered, but then promptly jumped the fence from cynicism to comfort, reassuring him that nothing would. And here comes the dilemma: Should we as surgeons project our fears onto a patient and their family or continue to showcase the false bravado on the exterior that most of us often portray? Is it okay to admit you’re sacred or is it your sole responsibility to make them feel safe? “I have full faith in you, I know you’ll do what’s best for me,” he declared. The real question was whether I had full faith in myself. I looked into my own centre for answers. It swung like a pendulum for a while and then replied, “You’ve got this, Mazda!”

The day finally arrived. We mapped a corridor to the brain’s secret chamber, parting the Sylvian fissure – a shimmering valley of veins – to reach the carotid artery. I gently dissected the silvery strands around it and reached the bifurcation, that glorious crossroad of risk and reward. The optic nerve, like a faithful sleeping partner, lies steadfastly next to the carotid artery. I dissected more strands, making more space. We surgeons are often in a hurry to get to the tumour, but like any climb to a majestic summit, the journey itself is what truly makes it spectacular. And in this particular approach, the view is unparalleled. Speckled stardust on glistening white optic nerves is a visual treat, even if you witness it daily. As I made space between the carotid artery and optic nerve, the redness of the tumour became visible, encircled by a leach of serpentine blood vessels pulsating with a bit of wrath.

We had visitors that day in the operating room; medical students and surgeons from other countries wanted to observe. It was the perfect case to showcase anatomy. But it was also the most frightening. As I was operating with a full heart and steady hands, I recalled the wisdom of the legendary neurosurgeon Dr. Harvey Cushing: “A surgeon is surrounded by people who are watching him, but inside he is alone.” It was my centre connected to Akshay’s; everything else was at the periphery.

The brain was still a little tight, like a stubbornly full suitcase. As the corridor narrowed, I opened up the anterior wall of the third ventricle and allowed for a gush of cerebrospinal fluid to reduce the pressure, akin to loosening a corset in a cramped room. The brain relaxed, the tension dropped, and the tumour’s disguise began to fall apart.

This offered more space between the sleeping partners. I teased the capsule of the tumour and entered it, quickly destroying its core. Pieces of it came running into my suction, eager to be swallowed from under the surface of the optic nerves. As we debulked tumour down to its final sliver, the normal anatomy began to fall back to place. The hypothalamus gleamed from below, the pituitary stalk glistened anteriorly, and the brainstem waved out from behind, with the basilar artery pulsating as if to say thank you. The surgery took 5 hours, and it was 5 hours of symphonic concentration, transforming complexity into choreography, where we danced around vision, pituitary function, thirst regulation, and life itself. We removed the tumour cleanly. Completely. “We have to see how he wakes up,” I told my assistant, a we prepared to close.

And that’s the cruel paradox about neurosurgery. The brain can look perfect under the microscope and still hold surprises when consciousness returns. When Akshay woke up, his vision was perfect. But a few hours later, he began emitting a litre of urine every hour and had an unquenchable thirst – a sign of hormonal dysregulation. The brain was revolting because we had messed with its centre. The next few days were cautious but kind, as we externally regulated the centre till its internal compass recalibrated. A few days later, he walked out of hospital with a balanced core.

The surgical centre isn’t a place. It’s a metaphor. For precision. For courage. For reverence. For knowing that everything from gigantic galaxies to nano neurons spins around something vital. And if you guard the centre, you protect the whole.

122 thoughts on “The surgical centre”

Zanurz się w warszawskim klimacie w Casino Warszaw Online – ruletka na żywo z krupierami mówiącymi po polsku, 3000+ slotów 3D i start z dopłatą aż do 1500 €! Poczuj elegancję Alej Jerozolimskich – bez wychodzenia z domu. Casino Warszaw Online oferuje Palace Gold Spin i wypłaty w 30 minut. Szukasz kasyna z duszą Warszawy? Premiowe kasyno mobilne to pełna legalność + bonus do 1500 €. Casino Warszaw – dla wymagających – demo i real w jednej aplikacji. Wejdź teraz i zacznij z dopłatą! Ruletka z jazzową oprawą – wszystko w Casino Warszaw Online. Licencja UE i program lojalnościowy Capital Stars czekają na Ciebie!

[url=https://www.intensedebate.com/people/NivinaIsaac]intensedebate.com[/url]

Zanurz się w warszawskim klimacie w Casino Warszaw Online – ruletka na żywo z krupierami mówiącymi po polsku, 3000+ slotów 3D i bonus 100% do 1500 €! Graj jak w salonie przy Grzybowskiej – wszystko w Twoim smartfonie. Oficjalne kasyno stolicy oferuje Palace Gold Spin i cashback do 30%. Chcesz grać w automaty z motywem stolicy? Premiowe kasyno mobilne to licencja UE + personalizowane promocje. Gry inspirowane Wisłą i neonami Grzybowskiej – demo i real w jednej aplikacji. Zarejestruj się i zacznij z dopłatą! Automaty z art déco – z interfejsem po polsku. Licencja UE i status VIP czekają na Ciebie!

[url=https://www.chordie.com/forum/profile.php?section=about&id=2435516]chordie.com[/url]

Poczuj klimat Warszawy w premiowym kasynie mobilnym – live ruletka z krupierami mówiącymi po polsku, ponad 3000 automatów premium i bonus 100% do 1500 €! Graj jak w salonie przy Grzybowskiej – wszystko w Twoim smartfonie. Casino Warszaw Online oferuje Vistula Sunset Baccarat i wypłaty w 30 minut. Chcesz grać w automaty z motywem stolicy? Premiowe kasyno mobilne to licencja UE + personalizowane promocje. Gry inspirowane Wisłą i neonami Grzybowskiej – 3000+ gier. Pobierz aplikację i zacznij z dopłatą! Live kasyno w 4K – wszystko w Casino Warszaw Online. Bezpieczeństwo SSL i status VIP czekają na Ciebie!

[url=https://www.weddingbee.com/members/gosesworks/]weddingbee.com[/url]

Zanurz się w warszawskim klimacie w Casino Warszaw Online – live ruletka z krupierami mówiącymi po polsku, bogata biblioteka gier i start z dopłatą aż do 1500 €! Poczuj elegancję Alej Jerozolimskich – gdziekolwiek jesteś. Casino Warszaw Online oferuje Grzybowską Ruletkę i cashback do 30%. Chcesz grać w automaty z motywem stolicy? Premiowe kasyno mobilne to pełna legalność + darmowe spiny. Kasyno z warszawskim charakterem – Megaways, jackpoty, live 4K. Pobierz aplikację i skorzystaj z darmowych spinów! Live kasyno w 4K – dostępne na iOS i Android. Bezpieczeństwo SSL i program lojalnościowy Capital Stars czekają na Ciebie!

[url=https://www.intensedebate.com/people/NivinaIsaac]intensedebate.com[/url]

Zanurz się w warszawskim klimacie w oficjalnym kasynie Warszawy – ruletka na żywo z krupierami mówiącymi po polsku, bogata biblioteka gier i start z dopłatą aż do 1500 €! Graj jak w salonie przy Grzybowskiej – gdziekolwiek jesteś. Casino Warszaw Online oferuje Grzybowską Ruletkę i wypłaty w 30 minut. Marzysz o live kasynie z polskimi krupierami? Premiowe kasyno mobilne to pełna legalność + bonus do 1500 €. Casino Warszaw – dla wymagających – 3000+ gier. Zarejestruj się i zacznij z dopłatą! Ruletka z jazzową oprawą – z interfejsem po polsku. Bezpieczeństwo SSL i program lojalnościowy Capital Stars czekają na Ciebie!

[url=https://www.weddingbee.com/members/gosesworks/]weddingbee.com[/url]

Zanurz się w warszawskim klimacie w Casino Warszaw Online – live ruletka z krupierami mówiącymi po polsku, ponad 3000 automatów premium i start z dopłatą aż do 1500 €! Doświadcz warszawskiego splendoru – wszystko w Twoim smartfonie. Casino Warszaw Online oferuje Vistula Sunset Baccarat i wypłaty w 30 minut. Marzysz o live kasynie z polskimi krupierami? Premiowe kasyno mobilne to bezpieczeństwo i przejrzystość + darmowe spiny. Gry inspirowane Wisłą i neonami Grzybowskiej – demo i real w jednej aplikacji. Zarejestruj się i zacznij z dopłatą! Ruletka z jazzową oprawą – z interfejsem po polsku. Licencja UE i cashback tygodniowy czekają na Ciebie!

[url=https://www.mixcloud.com/NebabayMulka/]mixcloud.com[/url]

Odkryj ducha stolicy w oficjalnym kasynie Warszawy – ruletka na żywo z krupierami mówiącymi po polsku, 3000+ slotów 3D i bonus 100% do 1500 €! Graj jak w salonie przy Grzybowskiej – gdziekolwiek jesteś. Casino Warszaw Online oferuje Vistula Sunset Baccarat i szybkie wypłaty dla VIP. Szukasz kasyna z duszą Warszawy? Casino Warszaw Online to bezpieczeństwo i przejrzystość + bonus do 1500 €. Gry inspirowane Wisłą i neonami Grzybowskiej – demo i real w jednej aplikacji. Wejdź teraz i skorzystaj z darmowych spinów! Ruletka z jazzową oprawą – z interfejsem po polsku. Audytowane RNG i status VIP czekają na Ciebie!

[url=https://www.openrec.tv/user/MiyecaHihik/about]openrec.tv[/url]

Cześć wszystkich! Chciałem się podzielić o GG Bet app.

Poszukiwałem dobrej apki do zakładów i znalazłem **ggbet aplikacja pobierz**. Gram od paru dni i powiem wam że to solidna rzecz.

[b]Sport:[/b]

– Football: Champions League, PKO BP, zagraniczne ligi

– Koszykówka: amerykańska koszykówka, Euroliga

– [b]E-sport:[/b] Counter-Strike, Dota 2, LoL, Valorant

– Tenis, MMA, siatkówka

[b]Kasyno:[/b]

– 3000+ tytułów od Pragmatic Play

– Slots z jackpotami

– Ruletka, blackjack, poker

– [b]Live casino[/b] w HD

– Free play – spróbujesz bez wpłaty

[b]Transakcje:[/b]

– [b]BLIK[/b] – 3 sekundy

– Karty kredytowe

– Skrill

– Przelewy ekspresowe

– Min. wpłata: [b]10 zl[/b]

– Cashout: 15 min (Skrill/Neteller), maksymalnie dobę (konto bankowe)

– [b]Zero prowizji[/b]

[b]Bonusy:[/b]

– Bonus powitalny dla nowych

– Cashback do [b]15%[/b]

– Freespiny codziennie

– Zakłady bez ryzyka na ważne mecze

– Program VIP – punkty na nagrody

[b]Ochrona:[/b]

– Encryption [b]SSL 256-bit[/b] (bank-level security)

– Licencja od sprawdzonego regulatora

– RODO

– [b]2FA[/b] (weryfikacja dwuetapowa)

– Responsible Gaming: limity depozytu, samowykluczenie

[b]Jak pobrac krok po kroku:[/b]

1. Otwórz oficjalną stronę GGBet

2. Kliknij zakładkę [b]Aplikacja/Mobile[/b]

3. Download [b]APK[/b] (dla systemu Android) lub przejdź do [b]App Store[/b] (iOS)

4. W Androidzie: włącz unknown sources w ustawieniach

5. Zainstaluj

6. Włącz app

7. Login lub sign up

8. Doładuj konto (min. 10 PLN)

9. Aktywuj premię

10. [b]Mozna grac![/b]

[b]Parametry: [/b]

– Rozmiar: [b]~50 MB [/b]

– Kompatybilność: Android 5.0+, iOS 11+

– Updates: auto-update

– Języki: Polski, EN, niemiecki, UA

– Widget (dla Androida)

– Powiadomienia push o jackpotach

[b]Moje wrazenia:[/b]

Gram już miesiąca i zero problemów. Aplikacja nie laguje bez względu na model. Support w języku polskim reaguje na czacie w chwilę – impressive.

Odds konkurencyjne, transmisje live w dobrej jakości. Interfejs przejrzysty, wszystko pod ręką.

[b]Wazna rada:[/b] Grajcie odpowiedzialnie! System oferuje opcje limitów. Ja ustawiłem próg dzienny i system notyfikuje przy przekroczeniu.

[b]Niedociagniecia:[/b]

Szczerze mówiąc – wszystko działa jak trzeba. Ewentualnie rzadko w godzinach szczytu loading trwa o kilka sekund dłużej, ale to naprawdę drobiazg.

[b]Gdzie pobrac:[/b]

Szukaj: [b]””ggbet aplikacja””[/b] → pierwszy wynik to oficjalny site → sekcja “”Aplikacja””

Alternative: App Store / Google Play (szukaj [b]GGBet[/b])

Questions? Chętnie odpowiem! Postaram się pomóc.

[b]Responsible gaming![/b]

PS. To nie jest reklamą – prawdziwy feedback.

Dodatkowe informacje:

[url=https://www.joindota.com/users/2313430-yacavalortaval]joindota.com[/url]

Zanurz się w warszawskim klimacie w premiowym kasynie mobilnym – live ruletka z krupierami mówiącymi po polsku, bogata biblioteka gier i start z dopłatą aż do 1500 €! Doświadcz warszawskiego splendoru – bez wychodzenia z domu. Casino Warszaw Online oferuje Grzybowską Ruletkę i cashback do 30%. Marzysz o live kasynie z polskimi krupierami? Casino Warszaw Online to pełna legalność + darmowe spiny. Casino Warszaw – dla wymagających – Megaways, jackpoty, live 4K. Pobierz aplikację i zacznij z dopłatą! Ruletka z jazzową oprawą – wszystko w Casino Warszaw Online. Audytowane RNG i program lojalnościowy Capital Stars czekają na Ciebie!

[url=https://www.weddingbee.com/members/lovasterirvano/]weddingbee.com[/url]

Hej! Gram na [b]ggbet aplikacja[/b] jakiś czas i mogę polecić.

Co mi się podoba:

– Masa slotów i live casino

– CS:GO, Dota, piłka, koszykówka

– [b]BLIK[/b] natychmiastowe wpłaty

– Bonus na start

– Czat PL non-stop

Apka waży tylko 50 MB, śmiga bez lagów. Wypłaty w 15 min na Skrill.

Pobieranie: oficjalna strona GGBet → sekcja “”Aplikacja””

Odpowiedzialnie!

Dodatkowe informacje:

[url=https://riversstormer.micro.blog/about/]riversstormer.micro.blog[/url]

Odkryj ducha stolicy w oficjalnym kasynie Warszawy – ruletka na żywo z krupierami mówiącymi po polsku, bogata biblioteka gier i bonus 100% do 1500 €! Graj jak w salonie przy Grzybowskiej – gdziekolwiek jesteś. Casino Warszaw Online oferuje Grzybowską Ruletkę i wypłaty w 30 minut. Marzysz o live kasynie z polskimi krupierami? Casino Warszaw Online to licencja UE + darmowe spiny. Casino Warszaw – dla wymagających – Megaways, jackpoty, live 4K. Pobierz aplikację i odbierz 100% bonus! Ruletka z jazzową oprawą – wszystko w Casino Warszaw Online. Audytowane RNG i status VIP czekają na Ciebie!

[url=https://www.openrec.tv/user/MiyecaHihik/about]openrec.tv[/url]

⭐ EKSKLUSIVERT TILBUD

Hent med en gang:

– 200% matchbonus (for eksempel 1000 kr, får du 3000 kr!)

– 270 free spins på utvalgte slots

– Totalverdi på over NOK 15,000+

SPILLUTVALG

– Slots: Starburst, Gonzo’s Quest, Book of Dead, Reactoonz

– Live Casino: Blackjack, Roulette, Baccarat med ekte dealere

– Table games: Poker, Videopoker

– Progressive jackpotter med livsendrende summer

TRYGGHET FØRST

– Offisiell lisens av Norsk Tipping

– Samme sikkerhet som banker

– BankID-verifisering for rask registrering

– Kvartalsvise kontroller av spillprosenter

– Personvern og 2FA

BETALINGSMETODER

– Bankkort med 3D Secure

– Norsk mobilbetaling

– Skrill, Neteller, MiFinity

– Bankoverføring fra norske banker

– Utbetalinger prosesseres innen 24 timer

VI ER HER FOR DEG

– Norsktalende kundeservice hele døgnet

– Chat, e-post og telefon

– Rask respons

– Guider på norsk

LOJALITET BELØNNES

Opptjen fordeler fra dag én:

– Gull-nivåer

– Høyere cashback

– Raskere uttak

SPILL TRYGT

Sett tidsgrenser. Ta pause når nødvendig. 18+. Spilleproblemer? Ring 800 800 40.

Start i dag på

[url=https://www.weddingbee.com/members/tasinomaskar/]KongKasino.top[/url] og motta din bonuspakke!

Odkryj ducha stolicy w Casino Warszaw Online – ruletka na żywo z krupierami mówiącymi po polsku, ponad 3000 automatów premium i bonus 100% do 1500 €! Doświadcz warszawskiego splendoru – wszystko w Twoim smartfonie. Casino Warszaw Online oferuje Vistula Sunset Baccarat i wypłaty w 30 minut. Chcesz grać w automaty z motywem stolicy? Premiowe kasyno mobilne to licencja UE + darmowe spiny. Kasyno z warszawskim charakterem – 3000+ gier. Wejdź teraz i zacznij z dopłatą! Ruletka z jazzową oprawą – dostępne na iOS i Android. Licencja UE i status VIP czekają na Ciebie!

[url=https://www.weddingbee.com/members/gosesworks/]weddingbee.com[/url]

Poczuj klimat Warszawy w oficjalnym kasynie Warszawy – live ruletka z krupierami mówiącymi po polsku, 3000+ slotów 3D i bonus 100% do 1500 €! Doświadcz warszawskiego splendoru – gdziekolwiek jesteś. Casino Warszaw Online oferuje Palace Gold Spin i cashback do 30%. Chcesz grać w automaty z motywem stolicy? Premiowe kasyno mobilne to pełna legalność + personalizowane promocje. Kasyno z warszawskim charakterem – demo i real w jednej aplikacji. Zarejestruj się i skorzystaj z darmowych spinów! Automaty z art déco – wszystko w Casino Warszaw Online. Licencja UE i program lojalnościowy Capital Stars czekają na Ciebie!

[url=https://yaritomamun.micro.blog/about/]yaritomamun.micro.blog[/url]

Wow, this post is fastidious, my sister is analyzing such things, therefore

I am going to inform her.

Cześć wszystkich! Chciałem się podzielić o mobilnym GGBet.

Sprawdzałem dobrej apki do zakładów i odkryłem **ggbet aplikacja pobierz**. Gram od miesiąca i mogę powiedzieć że to solidna rzecz.

[b]Bukmacher:[/b]

– Piłka: Liga Mistrzów, Ekstraklasa, Premier League

– Basket: amerykańska koszykówka, europejskie rozgrywki

– [b]E-sport:[/b] CS:GO, Dota, LoL, Valorant

– Tennis, MMA, siatkówka

[b]Automaty:[/b]

– 3000+ tytułów od top dostawców

– Slots z jackpotami

– Ruletka, BJ, poker

– [b]Krupierzy na zywo[/b] w wysokiej jakości

– Darmowe gry – zagrasz bez wydawania kasy

[b]Platnosci:[/b]

– [b]BLIK[/b] – 3 sekundy

– Karty kredytowe

– Neteller

– Przelewy ekspresowe

– Minimalna wpłata: [b]zaledwie 10 zlotych[/b]

– Cashout: kwadrans (Skrill/Neteller), do 24h (konto bankowe)

– [b]Bez oplat[/b]

[b]Oferty:[/b]

– Welcome bonus po pierwszej wpłacie

– Zwrot środków do [b]15%[/b]

– Free spins codziennie

– Freebety na ważne mecze

– Klub lojalnościowy – punkty na nagrody

[b]Bezpieczenstwo:[/b]

– Szyfrowanie [b]SSL 256-bit[/b] (bank-level security)

– Licencja od sprawdzonego regulatora

– Ochrona danych RODO

– [b]2FA[/b] (dwuskładnikowe logowanie)

– Responsible Gaming: progi wydatków, self-exclusion

[b]Instalacja krok po kroku:[/b]

1. Otwórz site GGBet

2. Wybierz zakładkę [b]Aplikacja/Mobile[/b]

3. Download [b]APK[/b] (dla systemu Android) albo otwórz [b]App Store[/b] (iPhone/iPad)

4. W Androidzie: włącz unknown sources w ustawieniach

5. Setup

6. Włącz app

7. Login lub zarejestruj nowe konto

8. Wpłać (min. 10 PLN)

9. Odbierz bonus

10. [b]Done![/b]

[b]Parametry: [/b]

– Rozmiar: [b]~50 MB [/b]

– Działa na: Android 5.0+, iOS 11+

– Updates: automatyczne

– Języki: PL, angielski, DE, UA

– Widget (dla Androida)

– Push notifications o jackpotach

[b]Moja ocena:[/b]

Gram już miesiąca i zero problemów. Aplikacja jest stabilna też na słabszym sprzęcie. Pomoc po polsku odpowiada przez czat w chwilę – bardzo sprawnie.

Odds konkurencyjne, mecze live płynnie. Wygląd prosty, łatwo się odnaleźć.

[b]Pro tip:[/b] Kontrolujcie budżet! W aplikacji są opcje limitów. Sam mam próg dzienny i system ostrzega gdy się zbliżam.

[b]Minusy:[/b]

Szczerze mówiąc – wszystko działa jak trzeba. Jedynie rzadko przy dużym ruchu loading trwa o sekundę dłużej, ale to naprawdę drobiazg.

[b]Link do pobrania:[/b]

Search: [b]””ggbet aplikacja””[/b] → pierwszy wynik to oficjalny site → zakładka “”Aplikacja””

Lub: App Store / Google Play (search [b]GGBet[/b])

Pytania? Pytajcie śmiało! Postaram się pomóc.

[b]Pamietajcie o kontroli![/b]

PS. To nie jest sponsorowane – prawdziwy feedback.

Dodatkowe informacje:

[url=https://rentry.co/osghu4hd]rentry.co[/url]

Witam! Chciałem się podzielić o aplikacji mobilnej GGBet.

Szukałem mobilnego bukmachera i trafiłem na **GG Bet app**. Testuję od kilku tygodni i powiem wam że jestem pozytywnie zaskoczony.

[b]Sport:[/b]

– Football: Liga Mistrzów, polska liga, zagraniczne ligi

– NBA: NBA, europejskie rozgrywki

– [b]E-sport:[/b] Counter-Strike, Dota 2, LoL, VAL

– Tenis, MMA, volleyball

[b]Automaty:[/b]

– Ponad 3000 gier od EvoPlay

– Automaty z progresywnymi jackpotami

– Roulette, BJ, poker

– [b]Live casino[/b] w full HD

– Tryb demo – możesz przetestować bez ryzyka

[b]Platnosci:[/b]

– [b]BLIK[/b] – natychmiastowo

– Mastercard

– Neteller

– PayU

– Minimalna wpłata: [b]10 zl[/b]

– Withdrawal: 15 min (Skrill/Neteller), maksymalnie dobę (przelew)

– [b]Darmowe[/b]

[b]Bonusy:[/b]

– Bonus powitalny dla nowych

– Cashback do [b]15%[/b]

– Freespiny regularnie

– Zakłady bez ryzyka na derby

– Program VIP – dodatkowe przywileje

[b]Bezpieczenstwo:[/b]

– Szyfrowanie [b]SSL 256-bit[/b] (bank-level security)

– Licencja od sprawdzonego regulatora

– Zgodność z RODO

– [b]2FA[/b] (weryfikacja dwuetapowa)

– Odpowiedzialna gra: progi wydatków, samowykluczenie

[b]Jak pobrac instrukcja:[/b]

1. Otwórz oficjalną stronę GGBet

2. Wybierz zakładkę [b]Aplikacja/Mobile[/b]

3. Download [b]APK[/b] (dla systemu Android) lub otwórz [b]App Store[/b] (iOS)

4. W Androidzie: zezwól na instalację z nieznanych źródeł w ustawieniach

5. Zainstaluj

6. Otwórz aplikację

7. Zaloguj się albo zarejestruj nowe konto

8. Doładuj konto (min. 10 PLN)

9. Aktywuj premię

10. [b]Done![/b]

[b]Techniczne: [/b]

– Rozmiar: [b]okolo 50 MB [/b]

– Kompatybilność: Android 5.0+, iOS 11+

– Aktualizacje: automatyczne

– Język: PL, angielski, niemiecki, UA

– Widget (Android)

– Push notifications o golach

[b]Co mysle:[/b]

Gram już miesiąca i zero problemów. Aplikacja śmiga płynnie nawet na moim starszym telefonie. Obsługa po polsku reaguje na czacie w pół minuty – mega szybko.

Współczynniki dobre, mecze live w dobrej jakości. Interface prosty, user-friendly.

[b]Pro tip:[/b] Grajcie odpowiedzialnie! Apka ma opcje limitów. Ja ustawiłem próg dzienny i system notyfikuje gdy się zbliżam.

[b]Niedociagniecia:[/b]

Honestly – nie znalazłem poważnych wad. Jedynie czasami przy dużym ruchu ładowanie zajmuje o kilka sekund dłużej, ale to naprawdę drobiazg.

[b]Gdzie pobrac:[/b]

Szukaj: [b]””ggbet aplikacja””[/b] → pierwszy wynik to oficjalny site → zakładka “”Aplikacja””

Albo: App Store / Google Play (szukaj [b]GGBet[/b])

Questions? Piszcie w komentarzach! Postaram się pomóc.

[b]Pamietajcie o kontroli![/b]

PS. Nie jestem sponsorowane – po prostu dzielę się opinią.

Dodatkowe informacje:

[url=https://www.joindota.com/users/2313430-yacavalortaval]joindota.com[/url]

Hej! Rzucę swoją opinią o GG Bet app.

Poszukiwałem aplikacji na sporty i znalazłem **GGBet mobile**. Używam od paru dni i powiem wam że naprawdę działa.

[b]Sport:[/b]

– Futbol: LM, PKO BP, zagraniczne ligi

– NBA: NBA, Euroliga

– [b]E-sport:[/b] Counter-Strike, Dota, LoL, VAL

– Tenis, MMA, volleyball

[b]Automaty:[/b]

– Ponad 3000 gier od Play’n GO

– Slots z jackpotami

– Roulette, BJ, Texas Hold’em

– [b]Live casino[/b] w full HD

– Darmowe gry – możesz przetestować bez ryzyka

[b]Platnosci:[/b]

– [b]BLIK[/b] – natychmiastowo

– Visa

– Neteller

– PayU

– Min. wpłata: [b]10 PLN[/b]

– Wypłaty: 15 min (e-portfele), do 24h (konto bankowe)

– [b]Zero prowizji[/b]

[b]Promocje:[/b]

– Premia na start na start

– Cashback do [b]15%[/b]

– Freespiny każdego dnia

– Freebety na derby

– Klub lojalnościowy – dodatkowe przywileje

[b]Ochrona:[/b]

– Szyfrowanie [b]SSL 256-bit[/b] (bank-level security)

– Regulowana działalność od renomowanego organu

– RODO

– [b]2FA[/b] (weryfikacja dwuetapowa)

– Responsible Gaming: progi wydatków, self-exclusion

[b]Instalacja krok po kroku:[/b]

1. Otwórz site GGBet

2. Wybierz sekcję [b]Aplikacja/Mobile[/b]

3. Pobierz plik [b]APK[/b] (Android) albo otwórz [b]App Store[/b] (iPhone/iPad)

4. Na Androidzie: zezwól na instalację z nieznanych źródeł w settings

5. Zainstaluj

6. Włącz app

7. Login albo zarejestruj nowe konto

8. Doładuj konto (min. 10 PLN)

9. Wykorzystaj welcome bonus

10. [b]Done![/b]

[b]Techniczne: [/b]

– Waga: [b]mniej niz 50 MB [/b]

– Działa na: Android 5.0+, iOS 11+

– Updates: auto-update

– Język: Polski, EN, DE, UA

– Widget na ekran główny (Android)

– Powiadomienia push o jackpotach

[b]Moja ocena:[/b]

Testuję od kilku tygodni i jestem zadowolony. Aplikacja jest stabilna bez względu na model. Support po polsku reaguje na czacie w 30 sekund – impressive.

Współczynniki dobre, transmisje live płynnie. Interfejs przejrzysty, user-friendly.

[b]Moja rekomendacja:[/b] Grajcie odpowiedzialnie! System oferuje narzędzia do zarządzania wydatkami. U mnie jest próg dzienny i system notyfikuje kiedy za dużo.

[b]Niedociagniecia:[/b]

Szczerze mówiąc – nie znalazłem poważnych wad. Jedynie czasami w godzinach szczytu ładowanie zajmuje o sekundę dłużej, ale to naprawdę drobiazg.

[b]Download:[/b]

Search: [b]””ggbet aplikacja””[/b] → pierwszy wynik to oficjalny site → zakładka “”Aplikacja””

Alternative: App Store / Google Play (szukaj [b]GGBet[/b])

Questions? Piszcie w komentarzach! Dzielę się doświadczeniem.

[b]Grajcie odpowiedzialnie![/b]

P.S. To nie jest sponsorowane – prawdziwy feedback.

Dodatkowe informacje:

[url=https://rentry.co/osghu4hd]rentry.co[/url]

Witam! Rzucę swoją opinią o aplikacji mobilnej GGBet.

Szukałem aplikacji na sporty i znalazłem **GGBet mobile**. Używam od miesiąca i mogę powiedzieć że naprawdę działa.

[b]Zaklady:[/b]

– Football: Champions League, Ekstraklasa, Premier League

– Koszykówka: NBA, Euroliga

– [b]E-sport:[/b] CS:GO, Dota, League of Legends, VAL

– Tennis, MMA, volleyball

[b]Automaty:[/b]

– Ponad 3000 gier od top dostawców

– Automaty z progresywnymi jackpotami

– Ruletka, BJ, Texas Hold’em

– [b]Krupierzy na zywo[/b] w HD

– Tryb demo – spróbujesz bez wpłaty

[b]Platnosci:[/b]

– [b]BLIK[/b] – błyskawicznie

– Mastercard

– E-portfele

– Przelewy ekspresowe

– Min. wpłata: [b]10 zl[/b]

– Wypłaty: kwadrans (e-portfele), maksymalnie dobę (konto bankowe)

– [b]Bez oplat[/b]

[b]Promocje:[/b]

– Welcome bonus dla nowych

– Zwrot środków do [b]15%[/b]

– Freespiny regularnie

– Freebety na ważne mecze

– System punktów – im więcej grasz tym więcej benefitów

[b]Ochrona:[/b]

– Szyfrowanie [b]SSL 256-bit[/b] (bank-level security)

– Licencja od sprawdzonego regulatora

– RODO

– [b]2FA[/b] (dwuskładnikowe logowanie)

– Responsible Gaming: progi wydatków, samowykluczenie

[b]Download krok po kroku:[/b]

1. Wejdź na site GGBet

2. Naciśnij zakładkę [b]Aplikacja/Mobile[/b]

3. Pobierz plik [b]APK[/b] (Android) albo przejdź do [b]App Store[/b] (iPhone/iPad)

4. Na Androidzie: zezwól na instalację z nieznanych źródeł w ustawieniach

5. Uruchom instalator

6. Włącz app

7. Zaloguj się albo zarejestruj nowe konto

8. Doładuj konto (min. 10 PLN)

9. Wykorzystaj welcome bonus

10. [b]Done![/b]

[b]Techniczne: [/b]

– Waga: [b]~50 MB [/b]

– Działa na: Android 5.0+, iOS 11+

– Updates: automatyczne

– Język: PL, angielski, DE, ukraiński

– Widget na ekran główny (Android)

– Push notifications o jackpotach

[b]Co mysle:[/b]

Testuję od miesiąca i wszystko działa. Apka jest stabilna też na słabszym sprzęcie. Support w języku polskim odpowiada przez czat w 30 sekund – bardzo sprawnie.

Współczynniki OK, transmisje live płynnie. Interfejs przejrzysty, user-friendly.

[b]Moja rekomendacja:[/b] Koniecznie ustawcie sobie limity! System oferuje narzędzia do zarządzania wydatkami. Sam mam próg dzienny i system automatycznie przypomina przy przekroczeniu.

[b]Co mozna poprawic:[/b]

Honestly – nie znalazłem poważnych wad. Ewentualnie czasami w godzinach szczytu ładowanie zajmuje o kilka sekund dłużej, ale to nie problem.

[b]Download:[/b]

Search: [b]””ggbet aplikacja””[/b] → oficjalna strona → sekcja “”Aplikacja””

Lub: App Store / Google Play (szukaj [b]GGBet[/b])

Questions? Piszcie w komentarzach! Dzielę się doświadczeniem.

[b]Grajcie odpowiedzialnie![/b]

P.S. To nie jest reklamą – prawdziwy feedback.

Dodatkowe informacje:

[url=https://rentry.co/osghu4hd]rentry.co[/url]

Sizzling Hot aplikacja – zagraj wszędzie!

Korzyści:

– Android – obie platformy

– Wpłaty BLIK – 3 sekundy

– Wszystkie wersje w jednej app

– Hot Race turniej – graj na żywo

– Bonusy mobilne

Download: [url=https://2tk.pl/wp-content/pages/?sizzling_hot_strategie___mity__fakty_i_realne_podej_cie_do_slot_w.html]Sizzling Hot Deluxe na pieniądze[/url]

Szczegóły: jak grać w Sizzling Hot -> [url=https://slonec.com/employer/blaszczyk/]link[/url]

Graj odpowiedzialnie! Odpowiedzialna gra limity bankroll sloty -> [url=https://pattondemos.com/employer/dreamdate/]link[/url]

Cześć! Testowałem Kasyno Warszawa Online kilka tygodni.

Plusy:

– Atmosfera [url=https://hogyvagy.com/author/kazukoboase96/]Marriott Warszawa[/url]

– 3000+ gier – sloty, ruletka, [url=https://www.vytega.com/employer/zyciewluksusie/]poker live[/url]

– Krupierzy PL 4K HD

– Wypłaty 15 min – 24h (moja: 780 PLN w 17h)

– Bonus 100% do 4000 PLN + 200 FS

– BLIK instant, min 10 PLN

– 50 MB – lekka app

Cons:

– Wagering 35x

– Brak crash games

Legalna, secure (TLS 1.3, EU license). [url=https://novatorentals.com/author/benjaminneuhau/]Live casino[/url] z Warszawy – rozmawiasz po polsku!

Mój bilans miesiąc: wpłaty 1200 PLN, wypłaty 1580 PLN = +380 PLN

Polecam dla miłośników [url=https://rsh-recruitment.nl/employer/wisla-plock/]luksusowych kasyn[/url] i [url=https://www.tokai-job.com/employer/wisla-plock/]kasyno aplikacja na telefon[/url]. Graj odpowiedzialnie!