In surgery, and in life, it all comes down to protecting the centre.

Everything revolves around a centre. The earth pirouettes around a molten core. The solar system hums to the rhythm of the sun. Cities pulse with life arounds their downtowns. A newborn baby at a family gathering is the centre of all attraction. And in today’s context, it’s the one working charging outlet at an airport where a desperate cluster of travellers vie for their device to be the next to enter its precious electrical orbit.

Even the brain, our crowning glory of evolution, bows to this unassuming truth – that life is regulated around its centre. Tucked deep within its protective vault rests a delicate core. Between the awakened pituitary and the sleep-regulating pineal gland lies the third ventricle ensconced by the thalamus on either side, the hypothalamus below and the union of the optic nerves guarding it – all quietly regulating sight, thirst, temperature, wakefulness, and hormonal symphonies that makes us ‘us’. You mess with the centre; you rattle the entire axis.

Akshay, a 30-year-old tall and lanky chap, much to his brain’s chagrin, housed a threat in exactly the same location. I had seen him a year ago when he came to me with dull aching headaches. The ophthalmological exam, for the so-called ‘window to the soul’, had come clean. But we neurosurgeons know better, that behind every window is a wall. And in his case, the MRI had revealed a small lesion trailing the optic chiasm, nestled near the third ventricle. Small. Subtle. Suspicious. More importantly, sentient, which I found out only after a year of watching it grow slowly but consciously. Due to the criticality of the location, him being relatively asymptomatic, and the possibly benign nature of the lesion, I had refrained from offering an operation. But now it was pushing against the optic chiasm, threatening to steal his sight. His sleep was a bit disturbed. He wasn’t eating well. The centre was misbehaving. And that’s the thing about central problems: They start quietly but rarely stay polite. We had no choice but to turn to the heart of our craft.

“What is the risk of this surgery?” he asked. “The tumour is smack in the centre of your brain,” I explained, detailing the anatomy lodged between hope and horror. “Anything can go wrong,” I surrendered, but then promptly jumped the fence from cynicism to comfort, reassuring him that nothing would. And here comes the dilemma: Should we as surgeons project our fears onto a patient and their family or continue to showcase the false bravado on the exterior that most of us often portray? Is it okay to admit you’re sacred or is it your sole responsibility to make them feel safe? “I have full faith in you, I know you’ll do what’s best for me,” he declared. The real question was whether I had full faith in myself. I looked into my own centre for answers. It swung like a pendulum for a while and then replied, “You’ve got this, Mazda!”

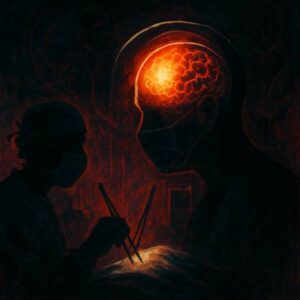

The day finally arrived. We mapped a corridor to the brain’s secret chamber, parting the Sylvian fissure – a shimmering valley of veins – to reach the carotid artery. I gently dissected the silvery strands around it and reached the bifurcation, that glorious crossroad of risk and reward. The optic nerve, like a faithful sleeping partner, lies steadfastly next to the carotid artery. I dissected more strands, making more space. We surgeons are often in a hurry to get to the tumour, but like any climb to a majestic summit, the journey itself is what truly makes it spectacular. And in this particular approach, the view is unparalleled. Speckled stardust on glistening white optic nerves is a visual treat, even if you witness it daily. As I made space between the carotid artery and optic nerve, the redness of the tumour became visible, encircled by a leach of serpentine blood vessels pulsating with a bit of wrath.

We had visitors that day in the operating room; medical students and surgeons from other countries wanted to observe. It was the perfect case to showcase anatomy. But it was also the most frightening. As I was operating with a full heart and steady hands, I recalled the wisdom of the legendary neurosurgeon Dr. Harvey Cushing: “A surgeon is surrounded by people who are watching him, but inside he is alone.” It was my centre connected to Akshay’s; everything else was at the periphery.

The brain was still a little tight, like a stubbornly full suitcase. As the corridor narrowed, I opened up the anterior wall of the third ventricle and allowed for a gush of cerebrospinal fluid to reduce the pressure, akin to loosening a corset in a cramped room. The brain relaxed, the tension dropped, and the tumour’s disguise began to fall apart.

This offered more space between the sleeping partners. I teased the capsule of the tumour and entered it, quickly destroying its core. Pieces of it came running into my suction, eager to be swallowed from under the surface of the optic nerves. As we debulked tumour down to its final sliver, the normal anatomy began to fall back to place. The hypothalamus gleamed from below, the pituitary stalk glistened anteriorly, and the brainstem waved out from behind, with the basilar artery pulsating as if to say thank you. The surgery took 5 hours, and it was 5 hours of symphonic concentration, transforming complexity into choreography, where we danced around vision, pituitary function, thirst regulation, and life itself. We removed the tumour cleanly. Completely. “We have to see how he wakes up,” I told my assistant, a we prepared to close.

And that’s the cruel paradox about neurosurgery. The brain can look perfect under the microscope and still hold surprises when consciousness returns. When Akshay woke up, his vision was perfect. But a few hours later, he began emitting a litre of urine every hour and had an unquenchable thirst – a sign of hormonal dysregulation. The brain was revolting because we had messed with its centre. The next few days were cautious but kind, as we externally regulated the centre till its internal compass recalibrated. A few days later, he walked out of hospital with a balanced core.

The surgical centre isn’t a place. It’s a metaphor. For precision. For courage. For reverence. For knowing that everything from gigantic galaxies to nano neurons spins around something vital. And if you guard the centre, you protect the whole.