Unsteady gait cannot be attributed to old age alone. A detailed neurological examination may help tackle an otherwise reversible problem

A seventy-two-year-old man was escorted into my clinic by his two able-bodied sons, each of them holding their father’s hand and elbow to support him better. He walked with a robotic tightness but with very little control over where his next step would fall. After about 8 minutes of trying to shuffle into a chair, he finally sat amidst a few moans. “Everything hurts,” he lamented. “My neck hurts, my back hurts, and I just can’t walk without support,” he groaned as he tried to adjust himself through his aches. “I feel like I’m walking on cotton wool,” he explained, narrating what many patients with cervical spinal cord compression specify.

“Any other problems?” I questioned. I usually allow my patients to finish saying everything they have to before I ask any leading questions. “My hands are weak and numb, and stuff keeps falling from them; I can’t button my shirt and my handwriting is like a drunk man’s,” he quipped. “How’s your control over passing urine?” I asked. He shook his head sideways and the corners of his mouth drooped with embarrassment at having to talk about it in front of his grown-up boys. “I’m extremely unhappy with my life,” he concluded.

In patients who have multiple complaints, I usually ask them one direct question to help me with my surgical decision-making. “Out of all your grievances, if there is one symptom I could help you recover from the most, what would it be?”

“I want to be able to count my money,” he said without the slightest hesitation, adding, “especially the 2,000-rupee notes. They just keep slipping out of my hand.” To lighten up the conversation a bit, I told him that I faced the same problem, but without any hand weakness to blame.

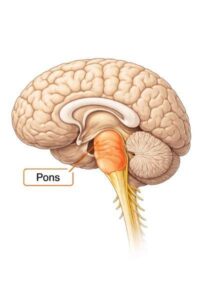

His MRI showed an overgrowth of bone and thickening of ligament that was compressing his spinal cord from the 3rd to the 6th cervical vertebrae. I pointed out to him the pencilling of his cord at those four levels. It was like a tourniquet that needed to be released for his spinal cord to be able to breathe again. Owing to the abnormal curvature of his spine that we could see, I explained why we would need to realign the spine by inserting a few screws and rod to contour it back to an elegant lordotic curve.

Within a few days, he was lying prone on my operating table with his head firmly fixed on a clamp. We use intraoperative neuro-monitoring for these cases that allows us to know if we are causing any damage to the spinal cord, because even a little manipulation in a compressed cord could lead to catastrophe. After cleaning and draping him in the usual fashion, we cut deeply down the centre of the back of his neck and separated the muscle off the bone. We then placed the screws as needed and cut a fine trough on either side of the four vertebrae to lift off the compressing element as a single block. This was executed to perfection but as soon as we decompressed the cord, there was a loud bellow from the back. “We’ve lost all our signals!” the physiologist exclaimed. This, in regular parlance, meant that the patient was completely paralysed – both hands and both legs. My heart sank into my stomach. This is the most unnerving piece of information you can ever give a surgeon in the middle of surgery.

The old man’s words, “I’m extremely unhappy with my life,” struck me even harder because I had potentially transformed that into abject misery. He would be awake but quadriplegic. I remembered something I’d read somewhere: “That’s the thing about unhappiness. All it takes is for something worse to come along and you realize it was actually happiness after all.”

Instead of being emotional and fraudulently philosophical, it was time to recalibrate and see if this could be reversed. I asked the anaesthetist to bring up the blood pressure and we started a steroid infusion. I always pray when I’m in deep shit. Within 20 minutes, the signals reappeared, and my heart began to gently rise back into its normal position. Sometimes, sudden decompression of a chronically compressed cord can result in precipitous changes of perfusion (the passage of blood) to and within the spinal cord. This can be disastrous if not recognized and dealt with immediately. To my absolute delight, he woke up without any damage. He stated that he felt much better, and by the time he was discharged, he said he felt less ‘tight’ and more secure in his balance.

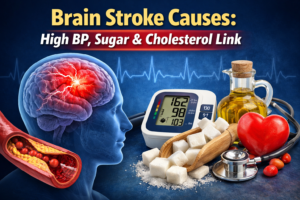

Imbalance while walking is not something that should be attributed to old age and left undiagnosed. Deficiency in Vitamin B12, especially in vegetarians or alcoholics, can afflict the spinal cord resulting in the same imbalance that a physical compression would. Diabetes damaging the nerves can cause one’s feet to burn and make them feel unsteady. A lumbar spine stenosis or even arthritic knees can make it difficult to walk. A disruption in the balance centres of the brain, certain brain tumours, or simply an excess accumulation of fluid in the brain can also make one’s gait unsteady. A detailed neurological examination is warranted before it can be attributed to old age; it would be negligent to miss out on corrective treatment for something that’s readily reversible.

Six months later, my patient walked into my clinic with his two sons, this time without holding their hands. He removed a crisp bundle of 2,000-rupee notes from his pocket and began to count them in front of me – effortlessly and cheerfully. Just when I thought (obviously in jest) that I would be at the receiving end of a few of those notes, he stuffed the stack back and gave me an empty but firm handshake. His grip was better than mine, and the power and function in his limbs were back to normal. And to me, that was priceless.