Why becoming a successful surgeon requires the same grit and dedication expected from a married couple, negotiating complexities of love and loss

“Neurosurgery should be your first wife, not your mistress,” a patriarch old-timer neurosurgeon was famous for telling all married resident doctors interviewing for a post-graduate training seat in the specialty. “And if you’re not married,” he used to caution, “it’s better to stay that way. It’s very hard for a relationship to blossom in the stressful environment of a residency program.” Those who interviewed for the post pretended to accede to his suggestion, although most married as soon as they got into the course – with varying outcomes, of course.

A vocation does need the exact kind of commitment one seeks from a marriage. You have to be imbued with grit and gumption. Our vocations (not professions) give us purity of desire and unity of purpose. “If you really want to make a wise vocation decision,” writes David Brooks, “you have to lead the kind of life that keeps your heart and soul awake every day.” In my opinion, this also applies to the decision of marriage. What you do for a living and whom you decide to marry would probably be the most important decisions of one’s life. But these too are not set in stone. You can course correct anytime. I know of doctors who have switched to politics, engineers who’ve turned actors, businessmen who’ve become monks and monks who’ve become millionaires.

A vocation, like a marriage, is a cure for self-centeredness. You are devoting yourself to a cause that’s greater than you. You tend to see how your patient or partner will benefit from you, rather than the other way around. And mastery in both requires that you do the same thing again and again, with the belief that it gets better and better. Like the big man Aristotle once said, “We are what we repeatedly do.”

Passion is the key element in both a vocation and marriage. When we were kids, every aspect of my life had a surgical correlation, as my dad, a surgeon himself, was so passionate about the vocation. “You have to learn to eat with a fork and knife,” he badgered us at every meal. “How else will you lean to be a good surgeon?” He taught me to use both hands simultaneously for everything. Often, food items on the dinner table were linked to tumours and other malformations we could correlate surgical pathologies with.

I later deciphered for myself that the art of diagnosis in medicine also lends itself to marriage. You look at a tumour on an MRI the same way you look at a potential life partner. Is it smooth at the edges or jagged? What does it do to the structures around it – just push them a little or encase them completely? Does it seem aggressive or peaceful? But most importantly, you ask, what does the core look like – is it solid or mushy? Is the tumour telling you the truth about itself and are you able to understand where it comes from? What feeds its soul?

You then understand and assess your own ability to handle such a case. Is this something you can operate on or need to refer to someone with greater experience, skill, and insight? Because while in most cases perception matches reality, on occasion, you can be surprised. What you think is benign sometimes turns out to be malignant, what sometimes seems ghoulish turns out to sweet and simple, or, like my kids would say, easy-peasy.

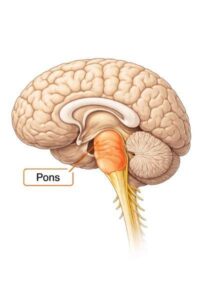

Often, you struggle through the entire operation but in the end, that struggle seems worth it. Rarely do you get into a tumour and very quickly realize it’s best to back out. Usually, you follow the middle path, and even if it’s hard, you keep at it. You work on it piece by piece wondering where it’s going to take you. You’re scared of injuring the wrong nerve or buzzing the wrong artery. If you want to give up somewhere in between, your assistant will goad you, the anaesthetist will encourage and egg you on some more, but after giving it all you’ve got, you realize that’s its best for both you and the patient to stop at this stage to avoid any further damage. Your patient came in smiling; you want to ensure they go back the same way.

Because, at surgery, just like in a marriage, you don’t want to have a complication you can’t get out of. “A failure”, says Atul Gawande “does not have to be a failure at all. However, you have to be ready for it. Will you admit when things go wrong? Will you take steps to set them right? Because the difference between triumph and defeat you’ll find isn’t about willingness to take risks, it’s about mastery of rescue.” The best doctors and hospitals don’t fail less, they rescue more. In my opinion, the same logic applies to marriages. We all need the ability to face complexity and uncertainty. Which means we all fail.

Primum no nocere is the Latin phrase that means, “First, do no harm.” In some variation, it is part of the Hippocratic oath that medical students take when becoming doctors. More than “Till death do us part,” I think, “First, do no harm” is a befitting marriage vow.

“We did the small things right,” said a famous team of surgeons after separating a pair of twins, conjoint at the head, over several staged surgeries, each lasting 24 hours. I believe these are the exact words most couples in long and joyous marriages use.

However intrinsically beautiful an operation is or how nightmarish it eventually turns out to be, whether you get into it with faith or fear, whether you come out of it smilingly or scathed, whether you end up hurting or healing, a few hours of complex surgery is like the years one spends in a marriage. After all, blood is involved – sometimes someone else’s, sometimes your own.