Prashanti Patel, a budding scientist (and a prolific writer) from Israel with a keen interest in neuroscience spent a day at the hospital with Dr. Mazda Turel and wrote this poetic piece.

Ever since man became conscious of himself and the environment, he has turned increasingly wondrous (and a little fearful) of the prowess of the seething electric activity that sits in his skull and directs his body. After all, an entire human community laid a stronghold upon Earth simply through the transformative powers of higher cognitive centres, even while, in contrast, another reptilian set of connections still persists and unfailingly elicits comic hysterics upon encountering a bemused cockroach. The demons of Hiroshima and the Holocaust arose from brains wired differently and a disastrous paucity of empathy, while the flood of oxytocin explains, in part, the propensity of the working professional to watch silly cat videos during lulls in Zoom meets. The human brain continues to be an object of wonderment in itself, as a harbinger of both genius and stupidity.

I was recently given the unlikely opportunity to have a dekho at this “thinker of thoughts” up close and personal and was predictably knocked out of mental breath. As an introductory aside, I am an aspiring fledgling scientist working with the calm, stoic plant kingdom but nursing an oddball fascination for blood and gore and a particular appetite for neurosurgery. I have long yearned to be admitted into the ranks of the neurosurgeon. However, being wooed by diverse interests and woefully dissatisfied with any one of them ensured that I finally careened my career off the railroads of medicine and into the metro of applied research. Nevertheless, I continued to harbour this yearning in secret, much like the typical soap opera vamp nurtures a cobra in her bosom.

A column by Dr. Mazda Turel, a renowned Mumbai neurosurgeon in the Sunday Mid-Day, caught my eye. I began to devour his writing. Much reading, wringing of hands, and a few email exchanges later, I let spring the proverbial snake I’d been nursing. He very kindly caught the non-biting end and suggested I come observe a typical day in his life. It was thus that I found myself at the doorstep of operation theatre (OT) no. 5 on floor 11 of the hospital he works at, my heart thudding, acutely aware of being a distinctive misfit in the seamless whir of a slew of pre-operative preparations. A quick change later, I stared at myself garbed in the clinical freshness of blue OT scrubs, cap, mask, and oversized Crocs, suddenly officious and tingling with excitement.

My first impression of neurosurgery was that of a cold, stern, but wondrous dance theatre act, with the anaesthetized protagonist cloaked in sterile drapes, sanitized, and centrally immobilized under a massive robotic pincer bearing a sterile-bagged scope and two giant lamps. With the exception of the two neurosurgeons and scrub nurse who are relatively restricted in movement as they fuss about the patient, the others perform graceful terpsichorean moves about the room, a coordinated orchestra of tearing open saline drip packs and fine instrument bags, adjusting levers and valves, helping dress the surgeons in scrubs, and generally maintaining order for what’s to come. Masking up means that communication is Kathakali-style, with a spectrum of expressions finding voice in the eloquent movement of ocular muscles, conveying exasperation (scrub nurse to principal surgeon), frustration (principal surgeon to scrub nurse), and joint responsibility (principal surgeon to assistant surgeon). The neuro anaesthetists are at home, nonchalantly strolling in place amidst the hum of beeping monitors and tangled wires, but with watchful eyes on the screens, ever so gently tuning gas flow and ensuring uninterrupted anaesthesia. I, as the fourth wall, had such an earnest desire to be useful that I occasionally assisted by pulling shut the OT door every time someone went in or out, earning myself a quizzical yet kindly glance of acknowledgement from the scrub nurse.

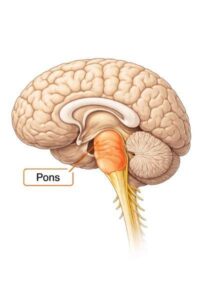

While neurons themselves are largely quiescent, some cell groups in the nervous system are occasionally rebellious, shoving past cell division checkpoints like commuters in a Virar (fast) local and enthusiastically foundering dynasties that disrupt normal function. Some of these tumours in the brain present additional challenges of inaccessibility, infuriating the surgeon and distressing his colleagues. I watched Dr. Mazda manoeuvre through two excruciating surgeries with the able aid of the assistant neurosurgeon and a sprinkling of colourful language. Both surgeries had contrasting aspects: one patient had a right frontal lobe tumour and the other had a tumour arising from the tentorium cerebelli, a glistening protective sheet that separates the cerebellum from the cerebrum. One could do with the relatively simple opening of the frontal cranium, but the other needed a tortuous inroad through the retromastoid route. Both procedures involved a lot of noisy suctioning, blood vessel cautery to stem bleeding, and copious requirements for absorbent patties, which the scrub nurse artfully arranged along with the other instruments on her trolley. No matter what the strain, Dr. Mazda in an avuncular fashion treated me to explanations of the origin and consequences of the tumour, readouts of the MRI scans, and the use of the silvery hemostatic pads that dammed the rivulets of blood seeping into the gaping cavities that once housed the angry engorged tumour. No textbook or video, though, could have prepared me for the sight of the brain itself, softly pulsing in synchrony with the heart monitor, every detail of its topography starkly visible through the scope and reminding me that the entire intangibility of my life’s experiences was wholly contingent on the smooth corporeal functioning of this organ. As the ‘good doctor’ controlled the last bit of torrential bleeding, the room too was silent, the obvious vulnerability of the patient weighing heavily on everyone’s shoulders, the only sound being a prodigious sigh from Dr. Mazda, who had just swallowed an expletive.

Once all patties that had gone in were extricated and tallied, the surgery culminated with a silent prayer under his lips and I followed Dr. Mazda into the OPD, where a string of patients with interesting symptoms and even more interesting descriptions of the same filed through. Here, too, I co-studied scans, read through histories, and understood that body language – not only words – instantly puts the sufferer at ease. It had been a full twelve hours since I’d left home when I finally pulled off the cap and mask, donned street clothes, and prepared to leave, adrenaline still coursing through my body as I yanked open the taxi door, while both starving neurosurgeons stayed on to observe the patient until she was wheeled into intensive care. A full week elapsed before I ceased looking at people as brains with bodies and resisting the urge to pry open their skulls.

0 thoughts on “The Surgical Observer”

Hello Doctor,

* I have had stomach issues, rashes on my legs or hands, and often cold and coughs since childhood. I used to have worms, stomach upset, stomach cramps regularly.

* When I was 3 I was diagnosed with Nephrotic syndrome. And was treated for the same till 5. After which was cured. Diagnosed as allergic to Combiflam and the medicine group.

* I was healthy and did not have to visit a doctor a single time when I was in Antwerp and Egypt (14-17).

* When I was 19 I had an episode where I was bleeding for 21 days. Had to get a D&C to resolve the ailment. This problem repeated when I was 29. Also had to be admitted to hospital for dehydration.

* Was diagnosed with retinitis Pigmentosa when I was 24. Under treatment for the same at Shankara Netralay.

* From 2007 to 2022 was extremely unwell. Symptoms: acid reflux, fainting spells, nausea, vomiting, extreme fatigue, frequent joint/back pain, anxiety, brain fog, water retention, pcos, stomach pain, stomach cramps, frequent diarrhoea, occasional constipation, dehydration, frequent colds and coughs leading to chest congestion, headaches, rashes on leg/ arms, occasional nerve pain, eosinophils were always elevated.

* When I was 30, had anaphylactic episode when I underwent cataract procedure.

* Visited multiple specialists during the above mentioned years. Was told my symptoms were in my head and were caused due to anxiety. It was only in 2020 that a gastroenterologist, made me do a food allergy tests and started me on the low FODMAP diet.

* Treated for h-pylori in 2022. Post which I started feeling better. But not completely as the bloating, acid reflux, diarrhoea, rashes, nausea, headache, brain fog, stomach pain/cramps persisted. The gastroenterologist put me on a liquid diet. But that did not suit me at all. It caused extreme diarrhoea followed by constipation.

* 2023 started consulting with nutritionist Bhakti Samant. Gradually over the year under her guidance I felt better. Stamina had improved, motions were better, but colds and occasional fatigue, giddy spells and bloating constantly resurfaced. Even on a disciplined diet and lifestyle, weight came down to 58.3 kg, but health wise I was not feeling 100 percent.

* 2023 December consulted allergist. Diagnosed with Dust allergy, pollen allergy.

* 2024 had dental treatment from February to June. Had 3 root canals. Always have been sensitive to antibiotics. After this treatment and the medicines administered whatever progress I had made went down the drain. All the symptoms resurfaced. Weight started climbing up no matter how restricted my diet. I realised I was again having inflammation.

* Consulted with Dr. Zareen (new allergist) in 2024 October. First time was diagnosed with MCAS.

* Dr. Zareen started me on winolap. But when after a month of treatment, my condition did not improve. She made me do a 24 hour test. She made the diagnoses of Mastocytosis with mastocytic enterocolitis.

* Currently weight has increased to 65.1 kgs. Fluctuates everyday depending on a flare up. Symptoms: occasional bloating, occasional tiredness, occasional headaches, occasional diarrhoea, occasional leg/back pain, occasional giddiness, belching.

* I have always been disciplined since childhood. But this level of discipline, where I can never indulge in anything or give myself a break, is quite taxing.

* Not able to tolerate: spinach, diary, gluten, tomato, jeera, chillies (red or green), cinnamon, shallots, mustard seeds, lemon, kiwi, orange, banana, dates, cashew nut, peanut, aubergine (this is from what I have personally experimented with)

* I was following Bhakti Samant’s diet. But lately a lot of things are not suiting me. And she was not aware of MCAS or the low histamine diet.

* In May 2025 had an extreme allergic episode when I tasted 1/4 th piece of chocolate brownie when in Mumbai. Was not informed or labeled it contained alcohol. Developed rashes all over and scalp and back rashes, along with giddiness and bloating. Upon advice of my allergist immunologist was taken to an emergency and administered – INJECTION AVIL 2 CC AND INJECTION DECADRON 8 MG SLOW IM

* We went to Kokilaben hospital. But since they were not aware of Mastocytosis, they began saline drip. And in the past as well my body has always reacted adversely to saline drip. Causing body pain, palpitation, giddiness, and extreme fatigue. Later, upon insistence they stopped the drip in between. And discharged me.

Current Medication:

* Allerbio Sachet twice a week

* Progut S sachet once a week

* Gloeye once in the morning

* Famocid 20 before breakfast and before dinner

* Budez 3 mg for 6 weeks

* Ketasma 1 mg 1.5 tablets at 7 pm

Current routine:

Wake up- 6:30-7

Do nasal rinsing and morning routine

7:30: bottle gourd lightly steamed juice

8-9: meditation and exercise

8:45: fruit

9: breakfast:

* Moong dal chilla with shredded cauliflower and white onion (2 nos.)

* Dosa and coconut chutney

* Idli and coconut chutney

* 1 1/2 egg with red capsicum and zucchini and 10 g makhana

11: fruit- peeled pear/ apple, red globe grapes, blueberries

1: lunch :

* Jowar roti (2), subzi (100 g), dal (1/4 th cup)

* Khichdi, subzi, fish (85g) or chicken (65g)

3-4: evening snack:

* Millet dosa

* Barnyard millet upma

* Dal dosa

6: soup

8: dinner

* Jowar roti (1), chicken curry, vegetable soup

* Chicken dry (120 g) and vegetables (100 g)

9:30: bedtime

This is my Daughter Trishna Damodar ..Message to Dr Mazda Taurel..please help

We are now based in Chennai