A surgeon recounts a poignant journey of a patient with terminal brain cancer, her resilience and profound acceptance of mortality, albeit with one caveat.

Jayshree came to me from Chandigarh over a year ago. She was in her mid-sixties and spoke her Hindi with a Punjabi twang. Her daughter sat next to her, trepidatious; they had made this arduous journey already knowing what was to come. She had a ghoulish brain tumour in her right temporal lobe. The moment I picked up the scan, from its beastly appearance, I knew it was Grade 4 cancer. “How did you happen to get an MRI?” I asked, since she looked relatively well to me. “I had a seizure,” she told me, “and my doctor asked for a scan,” she narrated simply. “I’m from a small town. I am resigned to my fate,” she surrendered.

After a detailed examination to ascertain she had no neurological dysfunction, I gently explained that she would need an operation to remove this tumour, followed by radiation and chemotherapy to control it, and “despite all of that, it would come back at some point,” I emphasized. “So then why are we going through all this?” she logically questioned. “It’ll improve your longevity by around a year or two,” I said honestly. “And I’m hoping even the quality of your life.” To most healthy people, adding a year to their life might not mean much, but to someone who has terminal cancer, it’s a lifetime. With Jayshree, we had gone from completely healthy to a diagnosis of end-stage cancer in a matter of days. It is a simple yet complex fact of life: things are neither separate nor identical.

We went ahead and removed Jayshree’s tumour. Under the high magnification of the surgical microscope, a world of intricate vascularity and delicate neural tissue comes into sharp focus. The discolouration of the tumour was clearly visible on the surface as I delineated it from normal brain. Its insides were necrotic and rotten – a grim testament to its aggressive nature. I used my suction as a fine tip magic wand in one hand while a combination of micro-scissors, dissectors, and bipolar forceps in the other hand worked in concert, their impossibly thin and precisely angled tips meticulously dissecting, coagulating, and teasing away the tumour, helping me get the whole thing out. Every subtle difference in texture, every micro-vessel, was magnified, allowing me to carefully navigate the treacherous interface between the malignancy and healthy neural pathways. Once complete, I methodically inspected the cavity for any remaining specks of abnormal tissue. The brain looked clean again – devoid of any unwanted intruder. The dura was carefully reapproximated, the bone flap was secured, and the scalp was closed in layers.

A few days later, she was discharged in pristine condition. No one could tell she had had major brain surgery. “Thank you,” she said with hands folded as she left to continue further therapy in Chandigarh. Her life was perfect for one year. She stayed in touch with me giving me regular updates about her wellbeing and sending me funny reels on Instagram. But then, her left foot started dragging. Almost nothing is as good as it seems, for the simple reason that nothing lasts.

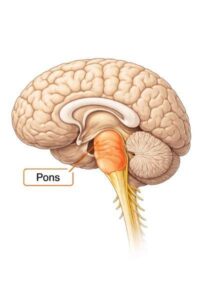

I asked them to repeat a scan, and as expected, the tumour was back – this time even more sinister, as it infiltrated the area of the brain responsible for leg function. “If I operate again, there is a high chance you’ll lose the ability to move your leg,” I told her, explaining that with the recurrence of the tumour her survival had been further shortened. And then, what she told me struck me like a gong. “Iss duniya mein koi amrut peekar toh nahi aata hai,” translated as no one comes into this world after drinking the divine nectar of immortality. Everyone who is born into this world is mortal and susceptible to the challenges, difficulties, pain, and ultimately, death that is inherent to human existence. It was a stark reminder of the fundamental vulnerability we all share, a truth that transcends individual suffering.

“What would you like to do?” I asked, giving her the options of considering one more surgery or continuing further chemotherapy. The choice was between more survival with a significant disability or shorter survival until nature rapidly induced the dysfunction. It was a moment where the limits of medical science met the raw reality of human mortality. Each of us is defined at heart by the questions that we ask; the answers we find are almost beside the point. “There is no right answer to this,” I explained, quoting my mentor, who used to tell all his patients who were faced with a dilemma, “Whatever decision you make will be the best decision for you.”

This profound truth resonated with an observation made by Thomas Merton, the American monk and prolific writer, who said, “Science can solve all our problems, except the deepest ones. For that there’s only one place we can go, and that’s within.” In that quiet consultation room, a soul confronted the ultimate question of how to live and how to face the end, knowing that the deepest answers were not in my surgical tools, but within her.

Jayshree went back home to try a second line of chemotherapy. Over the ensuing months, her hair withered away, her skin crumbled, and parts of her didn’t want to live anymore. I wondered about the thoughts that might be plaguing her. Her wishes and her desires. What questions do people ask themselves when the end is eminent, when there is time for introspection? How hard is it to cling to a positive outlook to life when life itself is in question? What does the brain contemplate, in its final moments, contemplating itself?

“I know my end is near. I have only one wish before I die,” she sent me a message a few weeks ago. “While I’m still in my senses, I want you write about me and share my story.”

Her words, uttered from the precipice of existence, were not a plea for more time, but a profound act of defiance against oblivion. It wasn’t just a surgical wish but her desire for meaning and connection, a final act of agency in the face of the inevitable. It was her legacy, her voice, echoing beyond the boundaries of her fading life.

My dear Jayshree, I hope you are reading this knowing that your story lives on forever, and that in every heart touched by your journey, a part of you will continue to bloom.

260 thoughts on “The surgical wish”

Я думаю, что Вы ошибаетесь. Предлагаю это обсудить. Пишите мне в PM.

керамическая плитка, https://allforarmenia.org/2022/05/03/emergensy-mission-3-support-to-khramort-refugees/ — идеальный выбор для отделки помещений. Она разнообразует в своих стилях и устойчива. Керамическая плитка легко обрабатывается, что делает ее популярной для ванных.

Вы попали в самую точку. В этом что-то есть и мне кажется это очень хорошая идея. Полностью с Вами соглашусь.

Олимпиады для школьников, https://hkmotorsport.dk/weekend-med-op-og-nedture-for-hk-motorsport-til-dsk-1-i-roedby/ — это отличная возможность узнать познавательные знания и проверить свои умения. Участвуя в таких соревнованиях, дети заботятся о критическое мышление и учатся навыки командной работы.

1xBet Betting, https://www.waysoft.net/winning-big-with-1xbet-betting-a-comprehensive/ – Betting through 1xBet предоставляет широкий выбор спортивных событий для ставок. Рто легкая платформа СЃ интуитивным интерфейсом Рё приличными коэффициентами.

Online Casino, https://www.watchesry.com/tag-heuer-carrera-chronograph-tourbillon-chronometer-replica-sale/attachment/53/ provides a thrilling encounter for players seeking recreation from the comfort of their homes. With various games available, players can try their luck and strategies anytime.

1xBet Betting, https://huntbconstruction.com/the-ultimate-guide-to-1xbet-betting-strategies-and-5/ – 1xBet Wagering предоставляет шансы для участников РїРѕ всему РјРёСЂСѓ. Легкий интерфейс Рё большое множество ставок делают его приоритетным выбором. РќРµ упустите время выиграть!

The security index of each casino is calculated after a thorough review of all complaints received by our complaint center, bethub login, as well as in addition complaints collected through other channels.