It may be anecdotal evidence most may balk at, but there is a gender, age connection to ideal in-surgery patient behaviour.

THERE is more than a 90 per cent chance that this will get better without surgery,” I told Nilesh, a 46-year-old gym instructor who had come to me with severe neck and left arm pain. He wore a tight black tee that delineated the curves of his torso. I’ve always wondered why people who pump iron go everywhere dressed as though they are still at the gym.

THERE is more than a 90 per cent chance that this will get better without surgery,” I told Nilesh, a 46-year-old gym instructor who had come to me with severe neck and left arm pain. He wore a tight black tee that delineated the curves of his torso. I’ve always wondered why people who pump iron go everywhere dressed as though they are still at the gym.

The pain had started a few days before he came to see me when he had lifted weights that were heavier than usual. It was now at a point where he could not lift his arm up, an act that unleashed an intense, undesirable pain.

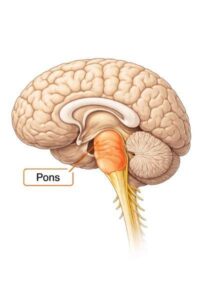

The MRI showed a large disc that had herniated out between the fourth and fifth cervical vertebra, compressing the nerve that supplied the muscles responsible for raising the right shoulder above the head as well as flexing the elbow, and hence the pain. “What you are experiencing is a combination of compression and inflammation. We will try a solution involving physiotherapy and medication, which works most often, but if it doesn’t get better, we might have to consider surgery to relive the compression from the nerve as a last resort. It’s called an anterior cervical discectomy.” I decreed.

“Surgery?” he sighed, folding in fear at my seemingly egregious suggestion. In my anecdotal experience, the people who are most apprehensive of surgery are well-built middle-aged men. Sometimes, taking an injection in their oversized gluteus maximus muscles is a nightmare for some. Those who are least perturbed about going under the knife are usually women, often lean and above 50.

There must be an inverse relationship between external toughness and inner fortitude.

Nilesh tried all modalities of the treatment I had prescribed, but after a slight initial improvement, his condition remained unchanged. In fact, he started developing a numbness in his thumb and index finger, and felt little spiders constantly crawl over his arm. Even an injection that combined a steroid and local anaesthetic didn’t work.

After about a month of trying a retinue of options, we agreed on surgery. As I explained what surgery would entail, his Adam’s apple started to enlarge; most relentless gym goers have a prominent one. When I explained that we would have to cut through the front of his neck to reach the disc, his face blanched. “Now would be the ideal time to take him to the operating room,” his resolute wife said, wondering why he was delaying the inevitable.

After a week of being cajoled by his family, he finally lay in front of us ready for an incision-pinioned under anaesthesia with no where to escape. We transversely cut along one of the skin creases over the front of the neck so that when it healed, it would be camouflaged nicely. We buzzed some of the small bleeders on our way to dissect between layers of muscles. The anatomy of the human neck is wondrous: If one dissects the planes carefully curated by nature, each layer opens in front of you like poetry mysteriously guiding you to a hidden treasure – illuminatingly beautiful. However attractive a good-looking neck is from the outside, the inside is insurmountably even more gorgeous.

We retracted the food and windpipe to one side and the carotid artery to the other, making space by snipping away at small strands of connective tissue that kept things together. A surgeon needs an extremely diligent assistant to perform this retraction; the laryngeal nerve responsible for vocal cord functioning and voice production traverses in the region, and any undue stretch can result in a patient waking up hoarse, which is devastating.

Any change in a patient’s voice after this surgery silences a little something within the surgeon.

As I moved inward into the neck, I started feeling bone with my finger and cleared up the final bit of fascia (tissue) with a peanut—a local name given to a contrived instrument that has a small ball of tightly rolled gauze at its tip to help us rub along the bone and expose the concerned glistening disc space which looks like a tiny speed-breaker.

With an X-ray, we then confirmed that we were at the intended level of the spine. We cut into it by clearing off pulpous-looking gelatinous material until we reached the covering of the spinal cord. With a pair of forceps in my steady hands, I pulled out the fragment of disc that had migrated behind the bone and was tormenting the nerve. “This last move has relieved one month of agony,” I pointed to my assistant. I took a ball-tip instrument to probe for any other fragments, but we were all clear. We placed a small implant to maintain the disc height and stitched him back up. “Close the skin meticulously,” I instructed, “or else he’ll curse us for the rest of our lives!” Most often, after the pain disappears, the scar is the one thing that continues to bother some of them because they can see it every day in the mirror. Here, again, it’s the bulky men who have a problem; the women deal with it and move on (or have adequate armamentarium at home to conceal it).

Nilesh woke up with a significant reduction in the tingling and numbness in his hand. He could lift his arm high up above his head, completely pain free.

I showed him the tiny fragment of the insolent disc that had been creating havoc in his life, the 2-3 mm of extruded gelatin that had devastated his day-to-day life. “So, size doesn’t matter after all,” he pondered profoundly in a clear voice—something we all end up realising at some point in our lives.