Sometimes, even in medical scans, things are not what they seem to be. So how does one plan a course of action? Or is better to let the mystery unravel by itself?

“This looks like a high-grade brain cancer,” I said, after looking at the MRI films of a middle-aged lady dressed in a green and white salwar kameez. Her rosy face instantly turned ashen listening to the news. Streaks of silver were strikingly visible through her thick black hair. Her anxious husband sat next to her. “Are you sure, doctor?” he asked, nervously playing with his fingers. “99%,” I assured, “but we’ll know for sure once we send it for testing,” I decreed. “And after surgery, this will need radiation and chemotherapy,” I stated, wanting to establish that they knew what they were in for. “We have two little children,” he said helplessly, probably foreseeing a fatality in his head.

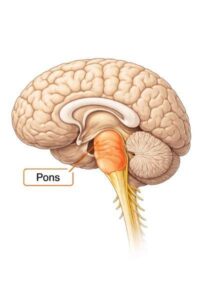

Reena had started forgetting things, which could seem to be more than usual for someone in their mid-forties. She was also finding it hard to find the right words for what she wanted to say. “She mixes up the names of things in the house,” her husband added. “She won’t be able to call what we sit on a chair, but will give its description instead,” he tried to explain the exact nature of the problem. “She’s unable to do the house hisaab as well,” he explained, implying a problem in performing calculations. “And that’s what prompted me to take her to the doctor,” he told me. Her physician rightly ordered an MRI that showed a big ghoulish mass in the lower part of the left parietal lobe, which was responsible for naming objects, counting, and calculations. The radiologist reported it to be a high-grade cancer of the brain and I concurred. “There’s no way this could be anything else?” her husband asked repeatedly.

In medicine, there is a theory: If you hear hoofbeats, think horses, not zebras. The zebra represents a rare disease. “Common things are common,” my professor used to say; ironically, that wisdom came from a man who saw uncertainty with such certainty. Because medicine is an imprecise and incomplete science. “If medicine is a science at all, it is a much softer science. There is gravity in medicine, although it cannot be captured by Newton’s equations,” Siddhartha Mukherjee wrote. We’re just about scratching the surface. I have friends and relatives constantly telling me, “You doctors don’t know anything,” to which I completely concur. “But the little that we do know might end up saving your life,” I sometimes retort.

“This could be something else,” I replied to Reena’s husband. “It could be an infection or an inflammation or demyelination,” I said, running through a list of possibilities for why there may be a space-occupying lesion in the brain. “But from the pattern of it and all the other information from the multiple MRI sequences, this, to me, looks like a malignant tumour,” I concluded. It is important to make a sound preoperative diagnosis because your surgical plan may depend on it. Would you be aggressive in removing it entirely? Would you want to send a piece of it to test while you’re operating? Would you be confident in telling someone they don’t have much more time based on a picture?

A few days later, we took her to the operating room. Through one of the crevices of the brain, between where she processed how to count and calculate, I teased the fine white strands apart, preserving the tiny arterioles of blood that nourish those areas. After about half an hour of dissecting, we made a space where there was none. “This doesn’t look like tumour,” I told my assistant. It was firm, rubbery, and scraggly. It wasn’t soft, mushy, and plump like the tumour we usually see. It was a cactus in the desert, not the pudgy foliage we were anticipating. Tumours are full of life. This was lifeless. Tumours sometimes make your heart race. This slowed me down. Tumours tell you what you’re getting into. This made me want to get out.

“This looks like TB,” my assistant muttered. “TB or not TB, that, my friend, is the question,” I joked, paraphrasing Shakespeare. “Being a prince, he found it so hard to live and contemplated dying. What if he actually had TB?” I continued the nonsensical conversation while tugging at those chunks of dead tissue. “Both were around in the early 17th century,” I added, laughing. “Hamlet would have turned in his grave if he had heard you just now!” he told me. We removed everything. The brain looked clean and pristine.

“The surgery went of uneventfully, but I must confess I’m not entirely sure if this is tumour,” I told the anxious husband waiting outside the operating room. “We’ve sent it for testing and we’ll know in a week. It looked very unusual,” I acknowledged. “If you weren’t sure, you shouldn’t have told me it’s cancer!” he exclaimed, lamenting, “I’ve spent a week of sleepless nights thinking about it.” “Things aren’t always what they seem,” I tried to philosophize, but words are seldom meaningful or helpful in these situations. “Let’s see what the final results show,” I comforted him with my hand on his shoulder.

Was I reckless with my interpretation of the scan, I wondered to myself once I got back to my office and thought about the case in my head. Nine times out of ten, this would have turned out to be a tumour, I reasoned; even the radiologist reported it to be so, I justified to myself. How does telling someone that they may have cancer impact their overall functioning? Going forward, should I be more careful in the way I speak to patients? And finally, the bigger question: Why aren’t things always what they seem? Maybe nature wants life to be mysterious and layered. Maybe it wants us to delve into its complexities. Maybe all of life’s work circles down to attempting to lift the veil. Except if you live in Saudi Arabia.

Reena was discharged three days later with a slightly improved ability to count and read. She was even naming things better. The final report concluded it was tuberculosis. “This is fully curable,” I told them when they came back a week later. Most people would be delighted with that news: no radiation, no chemotherapy… just a bunch of tablets and life could get back to normal. But the husband continued to look upset; he was displeased about what he had gone through while waiting for the final verdict. When I asked him, he said, “Patients latch on to every word that comes out of a doctor’s mouth; it’s considered the gospel truth!” he articulated.

I suppose, even when the sole intention is to do no harm, one inevitably and occasionally could end up hurting someone. Even when an intricate operation is performed well, it is important to remember that this is just a miniscule portion of the patient’s entire experience. Even when things appear as they are, sometimes they aren’t.

I constantly think about what it means to be a surgeon. And every time the answer oscillates: To be or not to be!