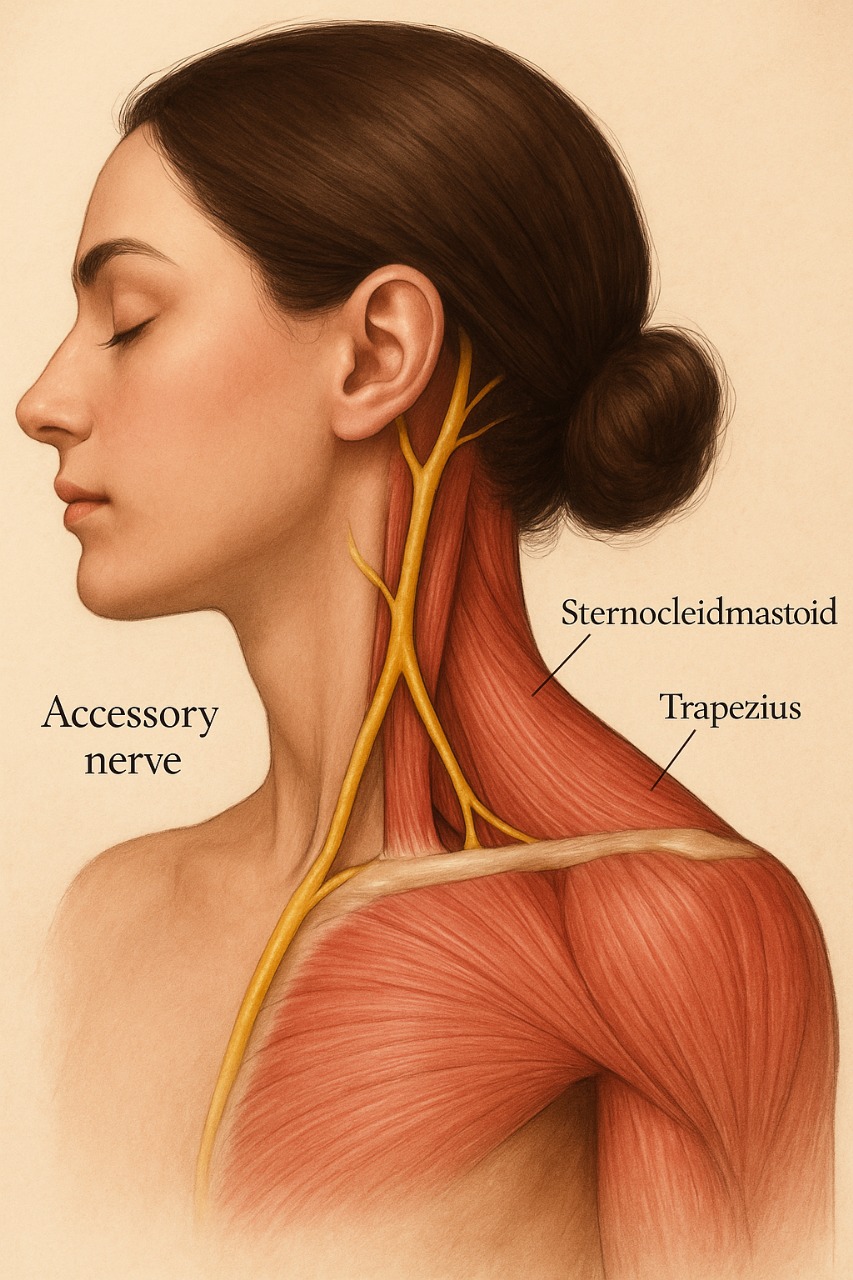

The eleventh cranial nerve, or the accessory nerve, is a fascinating component of our neural orchestra. Imagine it as the unsung hero, the crucial control cable specifically designed to empower two wonderfully expressive movements: shrugging your shoulders (perfect for feigning ignorance or expressing exasperation) and turning your head away from your shoulder (excellent for avoiding awkward eye contact or perfecting that dramatic exit). It is the invisible conductor for two large muscles: the trapezius, which forms the broad sweep of your upper back and shoulders, and the sternocleidomastoid, the prominent muscle running from behind your ear down to your collarbone – think Katrina Kaif and Deepika Padukone. Without the diligent work of the accessory nerve, these muscles, like marionettes with a suddenly severed string, simply cannot perform their vital dance. They’d hang there, looking rather deflated.

When Elara first walked into my clinic, she exhibited a subtle asymmetry that immediately caught my eye. Her right shoulder sagged ever so slightly, looking like it had given up on life. She spoke with a quiet frustration, describing a persistent dull ache in her neck and an increasing difficulty with everyday tasks that most of us take for granted. “Doctor,” she began, “I can’t seem to lift my right arm properly, especially to comb my hair or reach for things on a high shelf. And shrugging…” she sighed. “It feels like I’m trying to lift a heavy weight with a loose rope. I can’t even give a proper ‘I don’t know’ shrug anymore when my kids ask for something I want to refuse!” her voice trailed off. When I asked her to turn her head forcefully to the left, towards the drooping shoulder, the effort was visibly strained. The sternocleidomastoid muscle, typically taut and ready for action, remained soft and unresponsive on the affected side. It was as though the electrical current to that particular motor had been drastically dimmed, leaving it feeling rather unmotivated.

My clinical examination strongly pointed towards a dysfunction of the eleventh cranial nerve. To confirm my suspicions, we ordered an MRI. The images, when they came, were remarkably clear, almost rudely so. There, nestled precisely where the eleventh cranial nerve emerged, was a small, pea-sized mass – a schwannoma. This benign tumour, a slow-growing entity arising from the nerve sheath itself, was acting like a relentless pebble placed squarely on a delicate wire, gradually pinching and silencing the vital signals that flowed through it. It was the neural equivalent of a little knot tied tightly on a perfectly good garden hose.

Operating near such a critical nerve, which is responsible for daily, involuntary movements that punctuate our every thought, is akin to performing surgery inside a ridiculously fragile clockwork mechanism. Any misstep could cause permanent damage. I explained the situation to Elara, laying out the options. The tumour was benign, but its relentless pressure meant her symptoms would only worsen over time. The only path to restoration was to ‘untangle the knot’, to carefully remove the tiny growth that was stifling her nerve’s potential. After careful deliberation, Elara opted for surgery.

Under the high magnification of the surgical microscope, the precise course of the eleventh cranial nerve became astonishingly clear. My micro-instruments, impossibly fine and controlled with breath-held precision, gently exposed the schwannoma, a pearly white lesion clinging to the nerve. With meticulous care, using the finest dissecting tools, I began to delicately separate the tumour from the nerve fibres. Step by agonizing step, the tumour was carefully lifted, dissected, and finally freed from the nerve, revealing the once compressed, now pulsating, pristine nerve underneath. The ‘control cable’ was liberated, ready to send its messages loud and clear once more.

The recovery, while gradual, was nothing short of miraculous, and surprisingly amusing to witness. Within days, Elara reported a subtle easing of the neck ache. Weeks turned into months, and with dedicated physical therapy, the marionette strings slowly reattached. The drooping of her shoulder began to recede and her ability to shrug returned, first faintly, then with growing strength. Soon, she could comb her hair with ease, reach for books on the top shelf, and turn her head with the smooth, uninhibited motion she had once taken for granted. The once-dimmed electrical current was now flowing freely, reconnecting the circuit of her movement. Best of all? She sent me a video of herself shrugging dramatically at her teenage daughter, a clear sign of full recovery and a restored sense of humour.

22 thoughts on “The eleventh nerve”

Dearest Dr Mazda sir ………

You have so easily explained the entire process of removal of tumor on the eleventh cranial nerve from brain of Elara that we traveled with you in OT ………

The art of your fingers with pen & your micro instruments precession movements are marvelous……..

Keep on using your precious fingers for noble cause my dearest Dr Mazda sir ……..

God bless & wishing you very very happy wishes for Navroze & New year in advance to you in particular & all your dear family members with Lots & lots of Love ❤️

Definitely brighten up Sunday mornings with your lucid literary surgical adventures!

Hi Doc,

I love it when patients have these sort of cases and come up to you

Do I sound like a sadist?

Oh no, it’s just that we get to read how meticulously you pen down each case and have it solved with dexterity.

Here’s to many more cases coming up to you so we can view them writ.

Thank you Doc and of course ‘thank you patients’

Thank you for this beautiful presentation.

Doc ,You have the Gift of the Gab and the Precision and Meticulous arty fingers that solve all Nervy problemsalong with Gids Grace n Mercy..You are Amazing !!

Another beautifully uplifting piece to brighten my Sunday morning!

Thank you Dr Mazda for sharing your gifts with us!

Be thou blessed; always and in all ways!

So well written Mazda👏👏

You have a way with words!

Such a well written description of a rare, difficult, yet so easily remediable problem. Easily remediable with correct diagnosis and your kind of delicate surgery with microscopic precision of course !

Another great Sunday with a Mazda turel special

Every weekend you give us a story, a smile, and at least one new word to terrify our medical vocabulary. This — week’s prize goes to “schwannoma”, which I’ll never hear without craving shawarma 🤣

Many nerves are discussed.

Eagerly awaiting for 12th nerve Vagus

As usual, well penned

Dear doctor, the 11th nerve!How we,ur readers would have known about all these nerves if it weren’t for ur writings.And to what might go wrong with them.

The difficult part of restoring their normal working, all redit to u.

A decision well taken , a surgery well done!!!

Kudos!!

Another very delicate surgery made to look so easy. The narration as usual simply superb. Carry on carron the good work. Dr. Mazda.

Dear Dr Mazda, I have no words to thank you for yr articles in respect of great content analysis, gold standards of work with such aplomb.

Your articles show clarity, are like gems , bring in some insight and much calm to the modern complexities.

Thanking you. With great joy & warm regards.

Manoj Dabral.

Excellent diagnosis and surgical precision!

Feeling wistful as we near the end of the cranial nerves. Wonder what will Dr Mazda write about next.

Every case you write about is a master class in anatomy, physiology and humanity at the very least.

I am always reaching out to trace the Latin origins 🙂

God Bless you and family. Happy New year and many more to come. Firoza and Zinoo Master

Congratulation doctor,you seems to be the best architect of human nervous systeme & brain.a good neurosurgeon at the same time.

Thank you Professor Turel! You make anatomy come alive — clear, engaging, and a real pleasure to read.

I was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease four years ago. For over two years, I relied on Levodopa and several other medications, but unfortunately, the symptoms kept getting worse. The tremors became more noticeable, and my balance and mobility started to decline quickly. Last year, out of desperation and hope, I decided to try a herbal treatment program from NaturePath Herbal Clinic. Honestly, I was skeptical at first, but within a few months of starting the treatment, I began to notice real changes. My movements became smoother, the tremors subsided, and I felt steadier on my feet. Incredibly, I also regained much of my energy and confidence. It’s been a life-changing experience I feel more like myself again, better than I’ve felt in years.If you or a loved one is struggling with Parkinson’s disease, I truly recommend looking into their natural approach. You can visit their website at www. naturepathherbalclinic .com