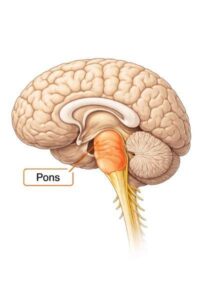

Beneath the toughness of the dura lies a layer called the arachnoid mater. Transparent and delicate, it drapes the brain like the finest of veils. One of my favourite writers, Maria Popova, once wrote that the brain “is a cathedral built of gossamer threads,” and nowhere is that truer than in the arachnoid. Under the microscope, it looks less like a membrane and more like spun sugar, or a spider’s web catching morning dew. It is beautiful, but it is also treacherous. When blood seeps into it, the cathedral darkens.

One evening, a woman in her fifties was rushed in with the sudden, thunderclap headache that makes every doctor move faster. “It felt like something exploded in my head,” she whispered on meeting me. She wasn’t exaggerating. A CT scan confirmed a subarachnoid haemorrhage – blood flooding into the delicate space beneath the arachnoid membrane. The culprit was a ruptured aneurysm at the junction of the anterior communicating artery, a tiny outpouching of vessel wall that had finally given way.

The thing about a subarachnoid haemorrhage is its drama. Patients go from reading the newspaper to collapsing on the bathroom floor in minutes. Families describe it as “she was fine, and then she wasn’t.” The arachnoid space, meant to cradle cerebrospinal fluid in quiet suspension, suddenly becomes a pool of blood – irritating, inflaming, threatening. It is one of the few neurosurgical emergencies that unites every department – the ER, radiology, the ICU, and the operating theatre – in a single collective gasp.

Surgery in these cases is not for the faint-hearted. Under the microscope, I opened the dura and began to peel back the arachnoid. It shimmered under the light, so fine you feared a breath could tear it. As the microscope magnified, you could see its filaments stretch across the sulci like tiny suspension bridges. To cut them is both delicate and dramatic, each incision revealing the anatomy beneath with the satisfaction of lifting tissue paper from a fragile relic.

The blood had matted down the arachnoid, staining its transparency and sticking it to the brain. I irrigated gently, teasing apart its folds. Every movement was slow, deliberate, reverent. And then, nestled in its web, the aneurysm revealed itself – a fragile blister on a vital artery, still oozing faintly.

Clipping an aneurysm is a test of nerve and humility. You dissect along vessels that supply thought, memory, speech, and movement, knowing that one wrong tug could silence them forever. The arachnoid is your guide and your obstacle, its translucent threads leading you toward danger but demanding that you not rush. Once the aneurysm’s neck was isolated, I placed a titanium clip across it, a tiny clothespin that would stop the bleeding but preserve the vessel. The moment the clip locked, the theatre seemed to exhale.

She woke the next morning drowsy but intact, her first words being, “The pain is gone.” Her family wept with relief, and one of them asked if the clip would set off airport security scanners. I assured them it wouldn’t. “Neurosurgery has enough drama; we try to avoid comedy at immigration!”

The arachnoid space, once bathed in blood, would take weeks to clear, but her recovery was underway. She would walk out of hospital lighter than when she had been carried in.

The arachnoid is often overlooked in anatomy classes, sandwiched between the dura’s toughness and the pia’s intimacy. But it is where life can turn in an instant. It is the lace veil that can be lifted to reveal beauty or torn to reveal catastrophe. In surgery, it teaches patience: the art of not rushing through the delicate in search of the dramatic.

There are many curves in a surgeon’s career – of learning, of judgment, of humility. The arachnoid, with its shimmering transparency, adds another: the curve of reverence. It reminds us that within this gossamer veil lies the difference between a mind extinguished and a mind preserved.

And sometimes, amid all the solemnity, you find humour too. When she visited me weeks later, the woman said, “Doctor, I survived an explosion in my head. Now my husband can’t complain when I shop for fireworks at Diwali.”

The arachnoid may be spun like a spider’s web, but its lessons are anything but fragile.

17 thoughts on “The Arachnoid”

What an exciting experience it must have been… ..knowing well what it’s consequences cud hv been.

Kudos to your skill and perseverance through this artistic experience .

Well done and May God always give you the patience, skill and faith in yourself to continue helping the world.

Really appreciate your actions and sharing so descriptively your process of surgery .

Dr. Mazda, a critical surgery but nicely handled and explained.

superb

Dr. Mazda, I’m truly amazed by the way you explain your experiences — your choice of words brings every detail to life and keeps me completely engaged throughout. As a science student, I could easily relate to the concepts, and it beautifully took me back to my college days. I’m sharing this article with my doctor friends so that more people can appreciate and learn from the depth of your knowledge and storytelling. Truly inspiring!

You are amazing with the pen and surgical too.who is mightier? It’s you of course. Be it the veil ,vein, nerve or blood clots,you handle all sorts so confidently.Bravo!!God Bless ! Thanks for sharing your thoughts and experiences

Dearest Dr Mazda sir ….

From Dura to Arachnoid, how your easy explanation is getting into the brain of common men in so simple and easy manner to make them understand so complicated procedure like a baccho ka khel 🫢

Only Your Writing of medical terminology in simple language is not only convincing but also very useful for people to understand the solutions of simple solutions to symptoms like headache and other medical conditions……😍

Of late your pieces are lacking one liner of Humor in the series explanation of the procedure 😎

Please continue enlighten us sir with your thoughts on various medical terminology in simple language with touch of humor too….🤣

God bless you with unparalleled wisdom and grace to keep on using your Fingers with pen & medical knife for all your patients 🌹

Nicely executed sir

I like how you said Neurosurgery has enough drama, we don’t need to add humor to it.. Great read!

Dear Mazda

I read your articles every Sunday in awe

It is blasphemy to render any comment on Devinches masterpieces.

You have inherited the dominant genes of the pen and the scalpel.

Unlike the neurosurgeons that I grew up with, You have embeded the genes of humility and wizardry in your DNA.

God bless you and your family

Dear Mazda

I read your articles every Sunday in awe

It is blasphemy to render any comment on Devinches masterpieces.

You have inherited the dominant genes of the pen and the scalpel.

Unlike the neurosurgeons that I grew up with, You have embeded the genes of humility and wizardry in your DNA.

God bless you and your family

Reply

Dr Mazda.. I love reading your articles on Sundays. U explain v simply& with a touch of humour as well. I look forward to reading them.

God Bless you & your family.

Sundays with Mazda. A day where neurosurgery meets storytelling.

All of us readers (fans of yours) are becoming honorary brain anatomists, one membrane at a time 🙃

Dr. Mazda you looks very calm and a simple person from outer.

But salute to your depth of knowledge and determination while you operate

God Bless You

Hi, Doctor Mazda. I always look forward to your Sunday articles. You are an excellent surgeon and a great human being. 👌 May God grant you many years of good health as you continue your work. I look forward to seeing you soon. 🇧🇼

Once again a treat to a novice to understand the beautiful anatomy of the brain.

I love reading and understanding through your articulation. Grateful for your work

Dear Mazda, may you never lose your skill or your humility. And humanity. Or are they all interlinked in a delicate interdependent web?

Reading this it wouldn’t b wrong to say ”A clip in time saves the brain”!!

Kudos !!! Ur sure a braveheart to handle n excel the emergencies… each dat…every day!!

LONG LIVE DOC!