The occipital lobe is the most misunderstood part of the brain. It sits quietly at the back of the head, doing its job without fuss, asking for no attention and rarely getting any credit. It does not think. It does not decide. It does not judge. It simply sees. And yet, without it, the world would be little more than noise and opinion.

I was reminded of this by a man in his early sixties who walked into my clinic wearing two different coloured socks, dark glasses at sunset, and an expression of mild irritation. He was a retired advertising executive, impeccably groomed except for the socks, which he explained were “a creative choice.” His wife, who had come along armed with medical reports and suppressed rage, announced that it was not creative. It was new. And it was worrying.

He had begun bumping into furniture. He complained that people appeared and disappeared suddenly. He once waved at a mannequin because he thought it was a neighbour. “Doctor,” he said earnestly, “my eyes are fine. It’s the world that seems confused.” His eyes were, indeed, perfect. The problem lay further back.

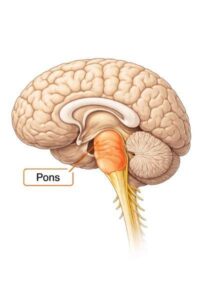

The occipital lobe is the brain’s visual processing centre. All visual information from the eyes travels backward, like gossip in a Parsi Colony, until it reaches this quiet corner of the brain. Here, light becomes form. Colour becomes meaning. Faces become familiar. A chair becomes a chair and not a Freudian couch. Damage this area, and people can see without understanding, look without recognising, stare without knowing why.

His MRI showed a largish arteriovenous malformation in the right occipital lobe. Slightly dramatic. Marginally flashy and enough to distort his visual world. A subtle betrayal by a structure he didn’t know existed.

When I explained this to him, he nodded thoughtfully. “So, this is why I can see my wife but not notice when she gets a haircut?” he asked. His wife looked at me as if surgery were optional but homicide was not.

Operating in the occipital lobe is tricky. You are not dealing with movement or speech but with perception itself. Under the microscope, the brain here looks deceptively calm and pale, almost shy. But every millimetre matters. A wrong move, and someone may lose the ability to read, recognise faces, or judge depth. The brain does not forgive clumsiness, especially at the back.

The surgery went smoothly. The lesion was removed with care, all the serpentine feeders being buzzed as required and that ghoulish leash of blood vessels carefully removed. He woke up asking whether the lights were always this bright. That, for us, was a good sign.

Over the next few months, his world settled back into place. Furniture stopped attacking him. Mannequins were not mistaken for humans. Socks began to match again. At a follow-up appointment, he told me, “Doctor, everything looks normal now. Slightly disappointing, actually.”

The occipital lobe teaches us a quiet lesson. We assume seeing is passive, automatic, effortless. It is not. Seeing is interpretation. It is the brain making sense of chaos, turning light into certainty. When it fails, we realise how much of reality is constructed inside our heads.

We talk often about perspective, about seeing things differently. It’s like someone once said: “Nobody sees what you see, even if they see it too.” Neuroscience reminds us that this is not a metaphor. It is literal. Change the brain, and the world changes with it.

Before leaving, my patient paused and said, “Doctor, I have one last question.” He leaned in. “If the occipital lobe is at the back of the brain, why didn’t I see this problem coming?”

I told him the truth. “Because some problems are only visible once you turn around.”

1 thought on “The Occipital Lobe”

Fascinating..you have unearthed and highlighted yet another unseen and unknown facet of the brain for us.