On the 31st of December, at 11 minutes to midnight, an indistinctive man in a black Parsi prayer cap opened the main door to the Udwada atash behram. He ceremoniously rolled out a red carpet on the intricately inlaid white marble of the magnificently restored fire temple.

Just before midnight, over a hundred Parsis of all ages arrived and waited patiently at the fire to honour the darkness and welcome the light. It was an ethereal experience to be in a space with one’s brethren, none of whom you could see but whose energies you could feel. The hall has no artificial lighting. During the day, natural light through ventilated windows helps you see. But at night, you see nothing except for the red radiance being emitted from the embers of sandalwood. We wait patiently for the priest to stoke the fire and were treated to the crackling whiff of sandalwood and a sudden burst of effulgence until the flame ebbed again slightly.

There were so many familiar faces around, none of whom I could actually identify, and, as it turns out, not many who could see clearly themselves. A gentleman praying fervently with his arms outstretched on a glass façade,assuming it to be the cabinet that housed the holy books, was startled with the gong striking one from within and realized he’d been mistakenly praying to the grandfather clock in the corner instead. An elderly lady standing next to me was struggling to maintain her balance in the dark and intuitively reached out for my hand. I held her and strengthened my grip a little to ensure she didn’t fall. “Homi, your hand is feeling very soft!” she gently whispered to me. “Aunty, Homi Uncle is probably standing on your right,” I whispered back, a smile beneath my mask. “Thank you,dikra… sorry,dikra,” she shuffled and held on to the right man.

Mobiles are to be switched off when one is on the sacred premises. But an elderly gentleman trying to find his footing turned on the flashlight on his phone and suddenly, in the midst of that intense calm, ‘torchbearers’ of the community started hustling him to turn the ‘torch’ off. Just as quickly, people silenced themselves as the head priest started praying.

The Udwada fire temple is the first atashbehram in India and hence its immense importance. After the Arab invasion of Iran, a group of Zoroastrians fled by sea and landed on the island of Dui in India. On the journey, they encountered a fierce storm and prayed to God for their safe arrival, pledging to build an atashbehram if they survived. In 721 CE, the sacred fire was consecrated in Sanjaan and remained there for 672 years. Seeking refuge from attacks on Sanjaan, it was hidden by priests in the Barot caves for 12 years and then moved to the Bansda forest, followed by Navsari, Surat and Valsad,until it arrived in Udwada in 1742. The sacred fire was installed at its current location in 1761 and has been kept burning ceaselessly since its consecration in Sanjaan.

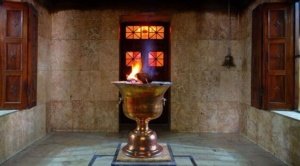

There is something magical about this fire that rests on a 5-foot tall silver base. The priest took six logs, each the size of an arm,and placed them crisscrossed over each other.He then placed their baby versions amidst them, what we call sukhar. Everytime my daughter sees a sandalwood stick placed into the fire, she’ll say, “The sukhar is getting killed!” And then I point out to her, “Look! It is also becoming something else.”

As the priest stoked the fire, what started off as a tiny flame progressively erupted into a giant fire several meters high, its incandescence lighting up the souls of each person in the hall, their faces finally luminous with the vitality of life. The smell of such effervescence can be felt in one’s bones.

People fervently held on to their loved ones, wishes were made, thanks was offered – all of it without voicing a word. The sonorous chanting of the priests’ prayers sent everyone into a trance. Each of us gently rocked within ourselves with our hands folded and were yet standing completely still. Then came a loud gong from the big bell within – the sound of which was amplified by the stillness of the night, sending a chill down the spine, signalling a transition: It asked us what we were willing to hold on to. With each of the nine bells that rang, hands were clasped tighter, and only when they came to an end did everyone breathe, releasing whatever they were willing to let go of. Once the prayer was over, most people started moving gingerly towards the exit, walking backwards to ensure they keep facing the fire until they left. Some zealously held onto the iron bars that barricaded the fire and continued their prayers. Some wouldn’t move from the marble threshold they were bowing down on while paying homage. All of us spoke to Godin our own way.

The New Year gives us a chance to glance over time’s figurative shoulder and introspect on how the past year has been,all the while possessing a conscious, constant desire to make the next one better. We look back on what has irradiated or perturbed our hearts and make changes that we think may help us. But whatever amends we seem to want to make, and however refreshing the start appears to be on the first day of the year, from the second day onwards, everything appears to be exactly how it’s always been. So much for choosing an arbitrary day in the year to mark the beginning of a new one!We’re lucky that in India, the number of religions we have offers us a New Year every few months or so; it gives us a chance to renew ourselves on a regular basis.

If you’re Parsi and you know it, try the midnight fire at the end of this year at Udwada. If you cannot, try again at the end of 2023, and then again at the end of the year after that,until after COVID restrictions on partying elsewhere have finally been lifted. Till then Happy Omicron to you.