A complicated eight-hour surgery to remove a spinal tumour against advice from colleagues in the OT, led me to the darkness of doubt. Before the sun came out again

He cautiously walked into my clinic with his brother. Rajesh was just 27 years old and wondered why his legs kept ‘giving way’ while walking. “I’ve had four falls in the past one month,” he moaned, perplexed about why this was happening to him in the so-called ‘pink of his health’. I reminded him that he was over 100 kilos and should refrain from using such a ‘rosy’ description of his well-being.“My legs feel heavy and tight and I’ve stopped driving cause I sometimes have no control over the accelerator – my foot just does its own thing,” he lamented.

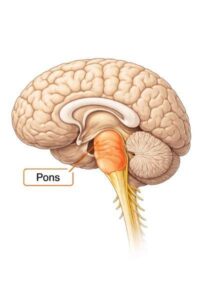

I made him lie down on the examining table to confirm my suspicion. I intertwined my hands behind his knees to check for spasticity. His legs were like logs – stiff and unwieldy. Then, when I bent the knee and pressed against the ball of his foot, the ankle went into a rhythmic jerky contraction that wouldn’t stop until I released the stretch. “This is what happens when you drive, right?” I demonstrated, and he acknowledged it. “It’s called clonus – Latin for turmoil,” I said clarifying his confusion. I completed the examination to note that he had lost a substantial sense of touch below the torso, and when I made him stand with his eyes closed, he instantly buckled and fell to the ground.

I pressed the MRI against the fluorescence of the viewing box to corroborate the diagnosis I had made in my head. And there it was. A four-inch sausage-shaped tumour inside his spinal cord, T2-T6. A sliver of normal spinal cord circumferentially wrapped the tumour, like the silver foil that encircles an Indian mithai roll. The surgical task was to eat the sweet completely while preserving the foil entirely. Any deviation from that goal could result in paraplegia, loss of bladder or bowel control, and sexual function. We endlessly discussed all the options open to him along with all their macabre outcomes. And then they left, probably more dazed than when they arrived.

I was told that the family, after comprehending the risks of surgery, had opted for alternative medicine, but Rajesh returned 3 weeks later with worsening gait and recurrent falls. My stance did not change. Surgery was the only option. He was admitted a few days later, but as I later understood, his family was still not ready for surgery. They opted for a discharge the same evening. I was a bit irritated, as extensive coordination and preparation is required for a surgery this intense, but at the same time, I was in some sense relieved that he would not be on my list of ‘complications’.

A week later, when he was finally admitted and in the operating room, we flipped him prone and made a one-foot incision down the middle of his back. This operation is performed with intra-operative electrophysiological neuro-monitoring of the leg muscles. If there is an undue stretch or distortion of spinal cord tissue during surgery, the physiologist fastidiously watching the computer informs us instantly and we subvert any potential harm by temporarily stopping the dissection or by moving to another area until the signals recover.

Here, however, they were unable to record any normal signal right from the start. We gave time for the muscle relaxant to wear off as we continued our exposure, cutting through bulky tissue and then sawing the bone to lift off ten spinal segments in one piece to fix back later. An hour later, the dura, which covered the spinal cord, was exposed. “Now try,” I said hoping for some response. Physiologists usually bellow since they always think they are providing extremely crucial feedback. Her silence made me turn around and look at her – she nodded her head sideways, to signal a no. They rechecked all their connections following the universal rule of hardware malfunction – almost everything works if you unplug it for a few minutes and plug it back. This didn’t.

I was left to make an epochal decision. Either proceed without signal feedback or re-attach his spine hinged at one end and close. I always involve my team in decision making even if subconsciously I already know what I’m going to do. “He’s 27, you can’t do this to him; he’ll be paraplegic for life,” said my compassionate anaesthetist, vetoing my plan to go ahead. “What if this is not a technical problem and he’s too spastic for the muscles to send normal signals? It’s going to be the same the second time around,” I tried to rationalize. “Or let’s wait for a few months till the tumour causes the paraplegia instead of you causing it today!’” the assistant interjected cheekily, clearly trying to wriggle his way out of a 12-hour operation if we decided to go ahead, something we’ve all done as ‘juniors.’

“Knife, please,” I announced, with my hand outstretched, and opened the dura exposing the ballooned spinal cord. All the fibres of the brain converge into this bundle, thick as the width of a thumb, to form the spinal cord, which was pushed to its edges by the tumour – much like a younger brother’s face tightly pressed against a wall by a bullying elder sibling. We zoomed the microscope for maximum magnification and incised the entire length of the spinal cord to identify the tumour. Painstakingly, we dissected tiny strands off it, buzzing the small arterial feeders supplying it. Over the next 8 hours,we laboriously isolated the entire tumour from the spinal cord and removed the ‘hot dog’ in a single piece – the silver foil seemingly intact. We closed in the normal fashion, restoring the anatomy laboriously, which we had defiled on the way in.

We flipped him over and the anaesthetist was quick to extubate him knowing we were all anxious to see if he moved his legs. And…he didn’t. Not even a flicker to deep pain. Even after he was fully awake a few hours later. This happens occasionally owing to the swelling of already compromised nervous tissue, but when there was no improvement even a week later, when it was time to be discharged, I had the realization that I’d made the worst decision of my life to proceed with surgery. As I saw him leave on a wheelchair (he had come in walking), I dug my palms deep into eyes, cursing myself for being so frivolous with someone’s future. I gave detailed instructions to the family on physiotherapy and other assistive devices.

These are moments when you question your craft. Your skill. Your ability to deliver in times of a complex crisis. You ask yourself if you are worthy of being in a position where someone’s life is in your hands. “It takes hundreds of good golf shots to gain confidence, but only one bad one to lose it,” said the golfing legend Jack Nicklaus. I was devastated. People assume that doctors are inured to complications and often annealed by them. I was heartbroken. I lost my sleep, hair, and appetite. Ars longa, vita brevis: “The art of medicine is long,” Hippocrates tells us, “and life is short; opportunity fleeting; the experiment perilous; judgment flawed.”

I operated on easy cases the next few days before venturing again into dangerous territory. I thought of Rajesh everyday and spoke to the family patiently every time they needed advice, tracking his seemingly imperceptible progress. A book by Cheryl Strayed was lying on my desk; I flipped to a random page and read a random line “Most things will be okay eventually, but not everything. Sometimes you’ll put up a good fight and lose. Sometimes you’ll hold on really hard and realise that there is no choice but to let go. Acceptance is a small quiet room.”

Six months later, on a sunny Tuesday evening, I got a video on my phone from an unknown number. It was of a man running and then climbing 22 stories. After the initial 30 seconds, I scrolled to the end. It was Rajesh. He had taken his own time to recover. Alone in my consulting room, I stood up, clenched my teeth, and pumped my fist in the air six times. I had hit a Roger Federer backhand winner, realizing its brilliance about half a year later.

Every ‘cord’ clearly has a silver lining.