Surgeons love the OR, but occasionally, a sharp clinical diagnosis—especially a rare condition—can bring the same satisfaction

Mahesh walked into my office with a bit of a limp. “My right foot is dragging,” he said, as he made his way uncomfortably to the chair in front of me. “I have a lot of back pain and it’s going down my right leg,” he showed me, gesturing with the palm of his hand. I listened patiently. “The orthopaedic doctor we saw told us it’s sciatica and suggested some medication and physiotherapy,” his anxious wife explained, “And now that he’s not better, they want to give him an injection,” she added, pulling out the MRI of his lumbar spine for me to see. Like most patients, she believed that’s where all the answers were. I allowed the films to sit on the table for a while.

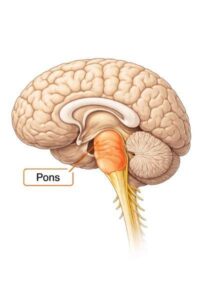

I’m delighted to have trained at a centre where we focused on clinical medicine. “Talk to the patient, hold their hand, touch them, examine them, and only then look at the scan,” the words of my teachers echo in my mind every day when I sit for hours in the OPD. I asked him to lie down and relax his leg, while I toggled my hands behind his knee and lifted it up a little to see it go into an uncontrolled jerky spasm. I took a reflex hammer and tapped the knee, and the leg was ready to fly out the window. “Your leg is spastic,” I professed. “This cannot be a problem in your lumbar spine; it has to be higher up,” I said, as I went on to check the sensations on his torso. The right side was entirely numb below his ribcage. I ordered an MRI of his thoracic spine instead, demonstrating a master class in clinical diagnosis.

There are very few days surgeons feel euphoric about sitting in the OPD; most of their savage joy is accrued from the OR. Mahesh got the thoracic MRI that evening itself, and the radiologist called me up excitedly. “There is a ventral spinal cord herniation at T8,” he announced, referring to the eighth thoracic vertebra. Not only had I hit the nail on the jackpot, but this was also an extremely rare condition, with me having operated on only one such case so far in my career.

“There are fewer than 250 reports worldwide of your case,” I told Mahesh when he returned a few days later with the MRI films. I drew a diagram to show him how a blob of his spinal cord had herniated through a defect in his dura (its covering) and that the forward traction on the nerves was causing the leg to drag. Being a mechanical engineer himself, he could fathom the dynamics with ease and understood that only surgery would fix this.

“I can’t be off work for more than two weeks; otherwise, what I’ve built over 20 years will collapse,” he gave me a warning. “We are used to working on ultimatums,” I humoured him a little. On a day soon after, I removed the T8 bone from behind and cut the dura. As I angled my microscope, I could see the spinal cord plunging into a 1 cm defect, much like a fat man falling into a manhole and getting stuck at the waist. We carefully pulled out the man and sealed the manhole by layering it with a patch in a slightly more effective way than the BMC does.

“I feel great!” Mahesh told me the next day. The strength was back, the sensations were getting better, and he felt like he had a whole new leg. The family was so grateful that more than the operation being successful, we were able to get the diagnosis right. I must confess I did pat myself on my back for my clinical acumen. Three days later the family went home, Mahesh walking out unaided. “Case number 251 in the world!” I told my team to add it to the list.

But a few days after that, his son called. “He hasn’t been able to move the right leg in the past few hours.” My relationship with pride and glee bent under its own weight and broke with an exhausted thud within a span of that single sentence. “Bring him urgently to the hospital,” I instructed, after asking a few relevant questions. I couldn’t help but think what my good friend often tells me – that no good deed goes unpunished.

The MRI done upon arrival showed a large blood clot (or so we thought) at the operated site compressing his spinal cord. “We need to take him back to the OR and relieve the pressure,” I said with a sense of urgency. “Now?” his wife asked alarmed, considering it was midnight. “Unfortunately, we don’t have a choice,” I clarified, requesting them to allow me to proceed. “I shouldn’t have had the operation to begin with,” I overheard him say behind the curtain as the family discussed their options. I had transmuted from an ace diagnostician to a failed surgeon within the span of one operation.

When we took him back to the operating room, we found no blood clot. In fact, the bulk of his own muscle had swollen and prolapsed onto the spinal cord causing epidural compression, which we relieved, also placing a titanium mesh over the bone to prevent the muscle from making contact. When the night had given way to day, the paralysed leg was moving again, anxious faces were composed again, and the vanquished surgeon had been resurrected again.

28 thoughts on “The surgical rarity”

Insightful article!

Clinical judgement for diagnosis is so relevant even today and hope it stays like that.

Well timed for Easter which is all about the Resurrection! Enjoyed the piece

Dear God,what an experience!One minute ur God and another minute ur such a failure. But as we know u now from reading about ur surgeries I knew u would set the stubborn leg right. Shows another of ur geniuses. God bless.

Giving hope to the anxious is something inspiring to read from Dr Mazda. Keep the flag flying. Happy Easter.

Another great miracle and grand success at what you do Doc. God bless you and help you to keep up the good work.

Great revelations! You are indeed gifted – medically, of course, and as an insightful writer too.

Ufff!! I can very well relate with that feeling Doc!! We have gone through in this situation!! 😊😊, but I am 100% sure, once patient is in your hand , he is in the safe hands!! Take care !! 😊, Happy Easter 🐣!!

This story reminds us that medicine is equal parts science, intuition, and soul.

The way you listen, diagnose, and carry both triumph and turmoil with grace is what truly sets you apart.

Life as a Doctor can be one hell of a rollercoaster ride. Grateful for healers like you, who stay the course 🤗

Sir, you are great.

Being a well trained clinician is a skill very few drs have these days!

The second surgery saved him from a life time of agony I believe!

Stay blessed doc!!

From HERO TO ZERO TO HERO that is how fickle the fame is..

A splendid Example of the value of good physical examination in the era of MRIs and echoes.

An art which is Unknown to the present generation of physicians.

God bless you sir and keep up the good work

India is truly blessed to have a neuro surgeon like you Mazda. Happy easter

Superb sir your timely action saved him from life time problem

Yes you are a good clinician

Thank you for Sharing. Your diagnosis was exceptionally insightful & precise. Your calm n composed demeanor is a true strength, Doctor. I deeply appreciate your dedication & professionalism. You are indeed a lifesaver for your patients.

You make no mistake when you operate so the problem arises due patient biological problem.

Doc, as I have told you earlier you are Gods gift to all …. Your humour & patient ear heals all.

I wish you all the best as you progress in your profession

Thank you for sharing your weekly articles.. Thoroughly enjoy reading them.

Hope you rested and had a great Easter

I tried some of these exercises after my ankle sprain, and the improvement was incredible. Get in touch with POS Rehab for expert physiotherapy and rehabilitation services. Our team is here to support your recovery journey with personalized care. Reach out to us via phone, email, or visit our center for consultations. Let us help you regain mobility and improve your quality of life. Phone:+91 98804 27202 or Website: https://posrehab.in/

Happy resurrection.

Dear Doc

Love your humour in your blog. Keep it up 👍

Appreciate the insights. It’s amazing how non-invasive therapy can ease chronic pain. Reach out to us via phone, email, or visit our center for consultations. Let us help you regain mobility and improve your quality of life. Phone:+91 98804 27202 or Website: https://posrehab.in/

Engaging showcase of services and success stories! The website conveys professionalism and patient-centered outcomes, making it easy to trust their expertise. POS Rehab for expert physiotherapy and rehabilitation services. Our team is here to support your recovery journey with personalized care. Reach out to us via phone, email, or visit our center for consultations. Let us help you regain mobility and improve your quality of life. Phone:+91 98804 27202 or Website: https://posrehab.in/

Love how you included both preventative and rehabilitative aspects of ortho physio. It’s a great reminder that physio isn’t just for injuries. POS Rehab might be able to help with posture correction and rehab: 📞 +91 98804 27202 | 🌐 https://posrehab.in

This was a fascinating case to read about. You presented it in a way that is both educational and engaging, especially for readers who enjoy learning about unique medical situations. The detailed explanations help make complex concepts more understandable. Thank you for sharing this rarity. POS Rehab is one of the centers I highly recommend: 📞 +91 98804 27202 | 🌐 https://posrehab.in

Such an insightful read. The way the surgical rarity is described makes it both educational and engaging. POS Rehab is one of the centers I highly recommend: 📞 +91 98804 27202 | 🌐 https://posrehab.in

A thoughtful and engaging article that explores an uncommon but important topic. The narrative style keeps the reader interested while still being informative. It’s refreshing to read content that combines knowledge with curiosity. Nicely done. POS Rehab is one of the centers I highly recommend: 📞 +91 98804 27202 | 🌐 https://posrehab.in

This was a refreshing and educational read — managing lower back pain often feels overwhelming, but your guidance brings clarity and hope. POS Rehab is one of the centers I highly recommend: 📞 +91 98804 27202 | 🌐 https://posrehab.in

It’s encouraging to know that with expert support like that offered at POS Rehab, even long-term spinal cord recovery can be effectively managed (📞 +91 98804 27202 | 🌐 https://posrehab.in