Robotic surgery may be the latest obsession in medical circles, but it can never replace the intuition and empathy — or sense of humour — of a human surgeon

Every few years, surgery gets a new obsession. A decade ago, it was keyholes. Then came lasers. Now, the flavour of the month or perhaps of the decade is robotics and AI. Everyone’s either getting robotic surgery, selling robotic surgery, or secretly Googling whether a robot will replace them.

Patients have begun to talk like tech critics. “Doctor, do you use the robot?” they ask, the way people ask if you’ve upgraded your phone. If I say no, they look mildly betrayed, as if I’ve confessed to using dial-up internet. If I say yes, they beam as if my robot and I cohabit.

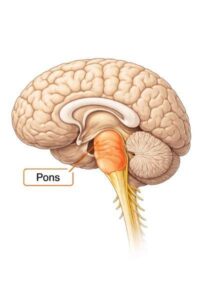

Last week, a gentleman with a slipped disc told me, “Doctor, I want robotic surgery.” “Sir,” I inquired, “do you mean minimally invasive surgery?” “No, no,” he replied, “I’m talking about the one where you don’t do anything – the robot does it all.” I told him that in that case, he should just stay home and let his washing machine operate.

We are living through what philosophers call a zeitgeist, a German word meaning ‘the spirit of the times’. The term first appeared in the 18th century and was used by thinkers like Hegel and Goethe to describe the invisible cultural current that shapes collective thought. Every age has its own: the 1920s had jazz, the 1960s had revolution, the 1970s had disco, the 1980s had bad hair, and the 1990s had Nokia phones that could survive the apocalypse. The surgical zeitgeist today is one of automation and precision, where machines promise to remove the last traces of human error… and possibly the humans too.

The truth, as always, lies between the hysteria and the scepticism. Robotics, navigation, and AI have genuinely improved spine surgery. They help us plan trajectories, reduce radiation exposure, and improve the accuracy of screw placement. The robot doesn’t tire, doesn’t sneeze, doesn’t flirt with the scrub nurse, and never complains about the temperature in the operating theatre. But it also doesn’t know when the tissue feels different, when the nerve looks unhappy, or when a patient’s anatomy politely decides to differ from the textbook.

In our quest for perfection, we sometimes forget that surgery is still a biological act. The human body isn’t a 3D printer file. It swells, bleeds, and sulks. It can’t always be persuaded to behave according to an algorithm. A robot can calculate; it cannot improvise.

Some years ago, a patient came in insisting on ‘endoscopic spine surgery’. His neighbour had had one and was back to golfing within a week. I looked at his MRI and explained that his disc had ruptured into several pieces, compressing the nerve like a badly folded wallet. “You may need a conventional microdiscectomy,” I explained. He frowned. “But isn’t that old-fashioned?” he asked. “So is gravity,” I said, “but it still works.”

Give us a new gadget and we’ll arrange a conference around it. Technology is seductive because it promises control, and medicine is full of uncertainty. The temptation to delegate our fallibility to a machine is strong. But if you depend entirely on it, you stop thinking. The danger is not that robots will replace surgeons, but that surgeons will start behaving like robots.

When used wisely, though, these tools are magnificent. I’ve used navigation systems that guide screw trajectories with millimetric precision, and endoscopes that slip through incisions smaller than a buttonhole. I’ve also seen what happens when someone uses these tools without judgment; it would be akin to watching a novice pilot attempt to take off in a jet because the manual looked easy.

A friend once said, “Technology should extend intuition, not erase it.” That’s the sweet spot. The best surgeries are still a symphony between hand, eye, and mind, not a solo by silicon. The robot can aim, but it’s the surgeon who must decide where to aim, and why.

Patients, too, are adjusting to this brave new world. One recently asked if ChatGPT could possibly plan her surgery. I said it would most probably write a very flattering post about it, but the sutures could turn out messy. Another wanted to know if I’d considered using a drone for spinal screws – it would be cheaper, he claimed. “Only if it comes with Amazon Prime delivery,” I quipped. We used to measure surgical brilliance by scar length and then by incision size, but now we do so by the number of screens we can stare at simultaneously. Some of my younger colleagues reckon that if an operation isn’t accompanied by a 3D animation, it may not be worth doing.

There’s also the practical side. Robots don’t complain, but they do malfunction. Once, midway through a surgery, the robotic arm froze. We restarted the console thrice, even called the engineer, but finally finished the surgery manually. The patient recovered beautifully. The robot, however, took longer to reboot – and probably still holds a grudge.

As a profession, we’ve constantly evolved. Trephination transformed into craniotomy, open surgery became minimally invasive surgery, and microscopes gave way to endoscopes. The best surgeons adapt, not because fashion demands it but because improvement does. The trick is to stay current without becoming a slave to the current.

I tell my younger colleagues that being modern doesn’t mean discarding the tried and tested. It means understanding the why behind the new. It means knowing that a robot can insert a screw straighter than you can, but it still needs you to know when not to insert one. It means remembering that empathy cannot be automated, and that no app can replace the quiet reassurance of a surgeon saying, “You’ll be fine.”

Technology should help us see better, not think less. It should make our hands steadier, not lazier. And if it does replace us one day, I hope it at least inherits our sense of humour – because surgery without it would be unbearable. The zeitgeist will keep changing – from open to keyhole, from keyhole to robot, from robot to who-knows-what-next. The trick is not to resist it, but not to drown in it either. Surf the wave but keep one hand on the shore.

As I finished my OPD clinic last evening, a patient asked if I’d soon have a robot doing my job. “Possibly,” I said. “But until it learns to drink cold coffee, respond to WhatsApp messages from three family members of a patient all at once, and smile when someone calls it Doctor Google, I think I’m safe.” The real trick, I told him, is simple: keep up with technology, but don’t get carried away by it. Be its master, not its minion.

He nodded thoughtfully. “So, Doctor, what do you call this approach?” “The human interface,” I said. “It’s still in beta, but it’s running quite well.”

For all its brilliance, AI still struggles with something profoundly human – hope. It can predict outcomes, but it cannot promise comfort. It can read scans, but not emotion. It cannot understand why a patient reaches for your hand before anaesthesia, or how a kind word steadies a trembling family in the waiting room. AI has surpassed our speed, our precision, even our memory, but can it look someone in the eye and give them courage? Can it look itself in the eye and accept failure? Surgery, at its heart, is still an act of faith between two people – one who trusts, and one who must be worthy of that trust.

18 thoughts on “The Surgical Zeitgeist”

Absolutely brilliant — I deeply resonant.

Having spent decades championing quality n excellence across industries, I couldn’t agree more that technology, however advanced, must remain an enabler, not a replacement for human judgment, empathy n intuition.

Whether it’s a robot in the OT or an algorithm in a factory, both are only as good as the human behind them, the one who thinks, senses n cares. Precision without perception is just mechanics; it’s the human touch that transforms outcomes into experiences.

Let AI assist, but let humanity lead.

I loved this text! It’s both funny, insightful, and profoundly true. You can feel the experience of the operating room and the reflection of a surgeon who keeps his feet on the ground despite the promises of robotics. If one day robots replace us, I hope they at least inherit your sense of humor!

Totally agree with your reading of AI. This is only the beginning……AGI will be the next improvement the other spinoffs will be magnificent leading to all around economic gains.

Well said Maz! Your comments today will resonate with every professional regardless to the field!

As for medicine, I pray that if I ever have to undergo surgery, the hand that wields the knife belongs to a person who also has kind, compassionate, understanding eyes and knows exactly my thoughts while I lie on that table!

Simple elegant insightful, that is Mazda.

I think sir robots cannot share their experiences with each other like surgeons share their experiences with each other and other juniors like you are sharing with us.I fully agree that technology should be used but with human touch.

As usual well written, humorous, precise and relevant. Robots may eventually human surgeons but not in the near future

Amaaazing!! The current zeitgeist should be writing like Dr Mazda Turel.

Your insights apply equally to several professions and fields of human endeavor.

I would still stick to our normal doctor doing surgery, what that robot change his mind I am a dead duck. God help all.

Very well articulated science and technology cannot replace the human touch.

Well written as usual, Mazda.

While the world debates AI, you make a strong case for something rarer and far more powerful – HI Human Intelligence (copyright pending)

HI has empathy, compassion, intuition, insight, and not to forget, oodles of humour 🙃

AI could never have written this particularly brilliantcolumn with its deep experience laced with such a fine sense of humour. 👍👍

I am 70 plus,and i still believe a doctor cutting me seeing my problem and dealing with his own good surgeon ‘s handsno robot for me ot my near and dear ones is a no no.

Great insights, thanks for sharing!

Health CRM Ai

The wisdom to blend the human component with the technology component is suavely highlighted in this article which every conscientious doctor should endeavor to profess. Beautifully and impeccably conveyed by Dr Mazda Turel.

Truly I got lost in your write ups. Its so good to read a good article.

Wish to meet you some day in future.

Relating to this article… my school going kids b like Y to study so hard wen AI is going to take up all jobs in the future!??

Mommy u too have all sort of machines fr ur household chores so Y cant the busy surgeons too use it at their disposal!!!

Time will decide the future of AI!!!

Till den b friends with ur doctor!!!